Click here to download this article as a pdf file

The Language of the Birds

Theatre music that cost a lot of effort but was never performed

Eija Kurki

In March 1911 Adolf Paul sent a telegram to Jean Sibelius asking for music for a new play that was to be performed at the Munich Hoftheater. The result was incidental music to Die Sprache der Vögel (The Language of the Birds), JS 62, which consists only of a single piece. Sibelius composed it for large orchestra and gave it the name Hochzeitzug [sic] (Wedding March). For potential theatre use he also gave instructions concerning the use of smaller orchestral forces.

Paul’s comedy The Language of the Birds has been performed in central Europe and England, but so far not in Finland or the other Nordic countries. Sibelius’s music has never been performed together with the play, although numerous attempts have been made to do so. This was a disappointment for both Sibelius and Paul; the playwright had hoped that Sibelius’s music would help him to score a success comparable to that of Kung Kristian II (King Christian II) some years earlier.

The correspondence between Jean Sibelius and Adolf Paul from the years 1899–1943, published in 2016 and edited by Fabian Dahlström (Din tillgifne ovän. Korrespondensen mellan Jean Sibelius och Adolf Paul 1899–1943), allows us to examine their fascinating and multifaceted collaboration. Dahlström has described Paul’s life and collaboration with Sibelius, and Hedvig Rask has written about his literary output in this volume. Paul was a champion of Sibelius’s music in Germany, and their friendship lasted for decades – until Paul’s death.

In this article I shall examine the origins of the music for The Language of the Birds with reference to the Paul/Sibelius correspondence and Sibelius’s diary entries. In their correspondence the incidental music – and the composition thereof – is mentioned frequently and in unusual detail, and is consequently interesting to follow. I shall also discuss performances of the play and attempts to have it performed.

I shall also try to answer a number of questions. What was the play actually like? Nowadays it has fallen into oblivion and is even more obscure than Sibelius’s music for it, which was recorded commercially for the first time in 1990 and published in 1997. Where does the name The Language of the Birds come from? Where has the play been performed, and why has Sibelius’s music not been used at these performances?

Adolf Paul and the theatre

Adolf Paul (1863–1943) was a Swedish writer with German roots: his parents moved from Sweden to Finland when he was nine. As children Sibelius and Paul were almost neighbours, as they both lived in the Häme region. Paul’s home was in Forssa, about 30 miles from Hämeenlinna.[1] They met and became friends, however, when they were both pupils at the Helsinki Music Institute and, like Sibelius, he was a member of the Leskovite circle that formed around Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924), who was then a teacher at the Institute (the circle was named after Busoni’s dog). After his time in Helsinki, Paul continued his studies in Germany, under Busoni (again) and others, and moved to Berlin as early as 1889. Paul then decided to become an author, writing both in Swedish and in German.[2] His first work, En bok om en människa, berättelse (A Book about a Man, 1891) contains a depiction of a composer named Sillén (i.e. Sibelius). In Berlin he belonged to a group of artists (Zum schwarzen Ferkel), that included August Strindberg and Edvard Munch, whom Paul knew well.

Adolf Paul in the 1880s

Photo: Daniel Nyblin, Helsinki (Public Domain)

Paul wrote more than thirty plays, the majority of which were published. A number of these were first performed at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki in the 1890s, and the most successful, the historical play King Christian II, was frequently on the programme. King Christian II, was also performed in Finnish, and was also staged in Sweden and Germany – like many of Paul’s other plays.

Paul’s plays were performed in a number of German cities (among them Berlin, Hamburg, Munich and Dresden). Often it was Paul’s comedies that were performed, but King Christian II was given in Berlin as well. Paul’s plays were also staged in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The first documented collaboration between Paul and Sibelius in the area of theatre was the music that Sibelius wrote for King Christian II in 1898. This was the season’s most popular production at the Swedish Theatre,[3] and Sibelius himself conducted the music at the première.

Paul asked Sibelius for music on a number of occasions, for example in 1903 when he wanted a violin piece for a new play: ‘For heaven’s sake write that violin solo, short and sweet – you can do it, nobody else can… You can write it in half an hour.’[4] Sibelius expressed interest in writing music for some of Paul’s plays – Harpagos, En ödemarkssaga (A Desert Tale) and Blauer Dunst (Sheer Invention). Blauer Dunst was also suggested as the basis for an opera. Paul also proposed ideas for pantomimes and films for which Sibelius could write music.[5] None of these ideas progressed beyond the planning stage,[6] so the tally of plays by Paul for which Sibelius wrote music was just two: King Christian II and The Language of the Birds.

Adolf Paul is depicted in Edvard Munch’s painting Love and Pain

(also known as The Vampire), 1893–95 (Public Domain)

The Language of the Birds and Orientalism

Paul’s three-act comedy The Language of the Birds was completed in 1911 and published the same year. The cover and title page erroneously claim that the play is in four acts.

The play centres around two elements. The first of these comes from the beginning of 1 Kings in the Old Testament, set in the time of Solomon. This book starts with the story of Abishag the Shunammite, who is brought to Solomon’s father, the aged King David, to provide him with warmth. ‘So they sought for a fair damsel throughout all the coasts of Israel, and found Abishag a Shunammite, and brought her to the king. And the damsel was very fair, and cherished the king, and ministered to him: but the king knew her not’ (1 Kings 1, 3–4). The second element is the Jewish legend that Solomon could understand the language of animals. The name of the play alludes to this ability, in particular to his knowledge of the birds’ language: ‘Solomon, it must be remembered, bore rule not only over men, but also over the beasts of the field, the birds in the air, demons, spirits, and the spectres of the night. He knew the language of all of them and they understood his language.’[7] The remaining thematic material of the play is Paul’s own invention.

The play has three main characters: King Solomon, Abishag and Sabud (Zabud). At the request of his brother Adonijah, Solomon has given Abishag to his friend and favourite Sabud to be his wife. Sabud may ask for an additional favour from Solomon but is unable to do so because in his opinion, having secured Abishag as his wife, he wants for nothing. Abishag urges Sabud to ask Solomon to reveal the secret of his wisdom – his understanding of the language of the birds. But first Solomon puts Sabud to the test: he must lie to his wife and tell her that he has already learned the secret but, on pain of death, he may not reveal it to anybody.

In Act II, Abishag attempts to find out the secret, and is offended and angry when Sabud refuses to tell. Just when Sabud has confessed that he does not know the secret, Solomon’s guards arrive and Abishag lies to them that Sabud has indeed revealed to her the secret of the language of the birds. Both are brought to be judged by Solomon.

In Act III, in the courtroom, Abishag wants Solomon to execute Sabud so that she can then marry him. Sabud, on the other hand, tries to kill Solomon with a dagger when he hears that Solomon plans to marry Abishag, who is just being prepared for the wedding. Abishag and the wedding procession arrive. Solomon does not execute Sabud, but demands that Abishag herself should give the command. But Abishag does not execute Sabud either; he forgives her for being prepared to have him killed. They flee the courtroom together. In the end Solomon gives the order to celebrate the wedding, even in the absence of the bride.

The reviews the play received after its première compared it to the work of August Strindberg, and stressed its anti-feminism – as shown for example by the whip used to discipline women in the play. Another writer with whose works The Language of the Birds was compared was George Bernard Shaw.

Old Testament-derived Oriental subject matter of the sort used in Paul’s play was familiar to Sibelius, as a few years earlier he had composed music for Belsazars gästabud (Belshazzar’s Feast) by Hjalmar Procopé (1868–1927), Op. 51 / JS 48 (1906), and Orientalism was in any case a fashionable topic around the turn of the century. Oscar Wilde’s Salome had appeared in French in 1893 and had been performed in Berlin in 1903–06, directed by Max Reinhardt. Richard Strauss saw this Berlin production when planning his opera Salome, premièred in Dresden in 1905.[8] Friedrich Freksa’s pantomime Sumurun, based on Oriental themes and with music by Victor Hollaender, was premièred in Berlin in 1910, also directed by Reinhardt. Sumurun enjoyed great success, touring in Germany and also receiving performances internationally, for instance in London in 1911 and New York in 1912.

In music, Orientalism was to be found not only in Richard Strauss’s opera, but also in earlier works such as Alexander Borodin’s In the Steppes of Central Asia (1880) and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade (1888), which is based on One Thousand and One Nights and formed the basis of an acclaimed Ballets Russes production in Paris in 1910.

The origins of the music

In the spring of 1911 Sibelius was working on his Fourth Symphony. In February he had completed two new pieces, Canzonetta and Valse romantique, for the play Kuolema by Arvid Järnefelt, the revised version of which had its première on 8 March. The first performance of the Fourth Symphony took place on 3 April and Sibelius worked on a fair copy of the score from late April until mid-May, sending it to his publisher Breitkopf & Härtel on 20 May.[9]

On 22 March 1911 Sibelius received a telegram from Paul asking for music for his new play, to be performed at the Hoftheater in Munich.[10] Paul followed this up with a letter in which he gave further details of the play and the music he wanted: ‘Dear Janne, Do me the great favour of writing music for my new play. It’s coming very soon at the Hoftheater in Munich and, to judge by how crazy they are about it, here in Hamburg and elsewhere, you could make some money out of it. As soon as it’s printed I’ll send you a copy. It’s called The Language of the Birds. The main role is Solomon, the heroine is Abishag from Shunem! (You know, the one who was brought to old King David to warm up his dying flames of life, and who was later given by Solomon to his friend Sabud, as his wife.) Just one piece of music, Oriental, drums, harps, cymbals, flutes and other stuff. To be heard first from inside the palace where she is being dressed for the wedding, – then the wedding procession approaches – (lots of eunuchs and court servants – the whole thing takes five minutes at most).’[11]

Hamburg, from where Paul wrote this letter, was then a very important place for the performance of his plays. Two of them had recently been performed at the city’s Thalia Theatre: Die Teufelskirche (The Devil’s Church) and Blauer Dunst.

Paul’s next letter was dated 19 April: ‘As we have permission to mention on the title page where the music can be purchased, and Breitkopf will surely agree to “duplicate” and sell it, I hope you have nothing against it if we write: “Music by Jean Sibelius from Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig. Score and parts”. I shall write and ask them, also for the sake of form, and ask them to get a proper fee from the directors.’ According to Paul, Albert Freiherr von Speidel (1858–1912), director of the theatre in Munich, was delighted that Sibelius would compose the music.[12]

Sibelius’s first reaction came in a letter to Paul dated 23 April 1911: ‘First of all send me your new masterpiece. Then I’ll know how much music is required. You should keep an eye on B & H.’[13] The same day he wrote to Breitkopf & Härtel: ‘I have no idea how much I have to compose, but I’m very keen to be of assistance to Paul.’[14]

In May Paul specified what he wanted Sibelius to do: ‘In fact the wedding procession in Act III and then at the end of the play are the places that need music. And – if you think so – perhaps the “birdsong” as well.’[15] The wedding procession in Act III comes from the following scene in the play, in which Abishag arrives to marry Solomon.

(The carpets covering the doorway are drawn aside. Out of the distance comes sound of trumpets, flutes and cymbals gradually nearing. The wedding procession approaches. First the musicians with harps, flutes, and cymbals, the girls, strewing flowers, then ABISHAG, splendidly attired with the royal circlet on her brow, the attending women, and last of all the PALACE CHAMBERLAIN, all with palm branches in their hands. SOLOMON standing erect in front of throne, gazing with triumphant mien at spectacle. Just as procession has reached steps of throne, he stretches out his hand commandingly. ABISHAG falls back a step. All stop. Music ceases).[16]

At the end of the play, too, Paul’s script asks for a wedding march: Solomon arranges a wedding without the bride, as Abishag has fled:

SOLOMON: Let it be served then! Let them play – wild music, maddening! Command the loveliest dancers! Let them show their skill! […] Music! (Music strikes up marriage march, and bridal procession, without bride, passes before SOLOMON, with deep obeisance and loud cries of joy. Procession disappears into palace. SOLOMON – alone – sinks down on the throne and remains seated, looking into blue vacancy with inward gaze.) CURTAIN. THE END [17]

The birdsong mentioned by Paul is heard on numerous occasions during the play, in the form of ‘twittering’ , ‘clamorous twittering’ or ‘violent twittering’ . Birds appear right at the start of the play:

(Apartment on ground floor of SABUD’S house. Fitted up in oriental style. In background, door and window, through which is seen garden, with trees and bushes in bloom. In foreground, to the right, stairs leading up to women’s apartments. On the right, a divan with cushions. SABUD sits on divan with crossed legs, gazing with melancholy air out into sun-bathed garden. Listens to twittering of birds, sighs dejectedly, and quite forgets his hookah, with the tube which he plays mechanically.) [18]

In the letter specifying where music is needed, Paul also writes: ‘On the title page we have printed that Janne’s music can be obtained from Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig. They were happy with that and wrote that you had mentioned it in a letter to them.’[19] In the printed edition of the play from 1911, however, this reference is missing.

After receiving a proof of Paul’s play in mid-May, Sibelius answered him: ‘There will actually be very little music – only a march. To engage a full orchestra for this little bit would be over the top. Therefore I’m considering using only wind and percussion instruments. I would like to do some birds’ twittering, but that too will fall by the wayside.’[20]

That summer, according to his biographer Erik Tawaststjerna, Sibelius called in the builders. The time had come to build the upstairs rooms that had been envisaged right from the start at the family home, Ainola, and to cover the log walls with cladding. In addition, on 20 June the composer’s wife Aino gave birth to a daughter, Heidi. The arrival of a new baby, the sound of hammering and the usual financial worries formed the backdrop to Sibelius’s work on Paul’s commission.[21] In his diary he wrote brief comments about his work on the march between 1 June and 17 July, and he finished the piece on 4 August.[22]

In mid-July Sibelius wrote to Paul that he was considering two options for the wedding march: ‘One march, Oriental, cold and wild, festive and brilliant. And another, the one I went for, festive, ancient and warm. In other words, poetic. I think it’s the right choice. After all, Solomon’s entire approach to the matter is warm.’[23] Paul replied that Sibelius might like to send him both marches.[24]

The Wedding March

Sibelius sent the score to Breitkopf & Härtel on 5 August, the day after its completion. ‘I have the honour of sending you herewith my “Wedding March” for orchestra, Op. 64. With simplified scoring the piece will be used as music for Adolf Paul’s comedy The Language of the Birds.’[25] The march is scored for 2 flutes, 1 oboe, 2 clarinets, 1 bass clarinet, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, timpani, triangle, side drum, tambourine, bass drum and strings. Surprisingly, he omits bassoons and horns.

The same day, Sibelius wrote to Paul that he had sent the material to the publisher, and indicated which instruments should play it. ‘On stage, this composition is played by sixteen musicians; they are: 2 flutes, 1 oboe, 2 clarinets, 1 bass clarinet, 1 trumpet, 1 trombone, 2 violas, 2 cellos, 1 bass, (triangle and side drum), (bass drum and tambourine, timpani). 16 performers in total. I have marked the score accordingly.’[26]

In this version the complement of woodwind instruments is unchanged, but the brass has been reduced to a single trumpet and trombone. The small string sections use just the lower instruments – violas, cellos and double bass. Sibelius tells Paul that, in the score he sent to Breitkopf, he had marked which players were included in the theatre version. In the composer’s original manuscript there is a marking that relates the first and second violins, suggesting that they should be omitted from the theatre version: ‘The violins play only if the orchestra is large’.[27]

In addition, Sibelius made – or started to make – a theatre version of the Wedding March for woodwind, one trumpet, two trombones, lower strings and percussion, but only a fragment of the opening has survived.[28]

By mid-August Sibelius was awaiting a reply from his publisher, and wrote in his diary: ‘Nothing from B & H. Is there something going on?! It wouldn’t be the end of the world if they, i.e. B & H, didn’t want to have the thing. In that case the principle of “having a nose for something good” would be alien to them.’[29]

Breitkopf did not accept the work for publication. The reason given was that they regarded the piece as so closely bound to the play that it could only be used in that context.[30] Breitkopf copied the score and sent the original back to Järvenpää.[31] The composer noted in his diary: ‘Bad news from B & H. They don’t want the Wedding March. I’ll have to try to take care of it with someone else. “Si male nunc et olim sic erit” [Though now we suffer, we shall not suffer always]! I never thought this could happen to me. Now there’ll be war!’[32]

The costs associated with the music created problems in their own right, and this topic crops up frequently in letters. Paul’s publisher became involved as well. After Breitkopf’s rejection, Sibelius suggested that Paul ought to pay for copying out the orchestral parts. Sibelius supplied the music for the première without payment and promised: ‘I shall take my revenge on B & H. Stay calm! Maybe in a “more refined” way than they are used to.’[33]

Two years earlier, Sibelius had sent the music he had composed for Mikael Lybeck’s play Ödlan (The Lizard) to Breitkopf & Härtel, whose specialist assessor, Professor Paul Klengel, had declared: ‘The music that accompanies The Lizard… is planned only in direct association with the events on stage, in the absence of which it will be barely comprehensible and will also be of scant interest.’[34] Now Sibelius’s work was rejected once again.

Sibelius first gave the Wedding March the opus number 64 – which was ultimately assigned to the tone poem The Bard. As a consequence of the Wedding March remaining unpublished, its opus number was changed several times, regardless of chronology. At quite a late stage it bore the opus number 8, which now belongs to the music for The Lizard. In the end the Wedding March was not given any opus number at all.[35]

The Munich première

The world première performance of the play took place on Sunday 10 September 1911 at the Residenztheater in Munich. The director was Albert Steinrück (1872–1929), who also played the role of Solomon. The 1911 printed edition of the play is dedicated to Steinrück ‘in recognition of our long friendship’.[36] Three days before the première, Paul wrote to Sibelius: ‘Heartfelt thanks for your beautiful music, which I heard for the first time today. As the stage is small, we have only forty people in the procession, so we’ve had to “abort” the music – otherwise we would have needed to engage several hundred extras, and that isn’t possible.’[37]

We know therefore that Sibelius’s music was played at rehearsals, but it evidently proved to be too long for the circumstances of the production; it would have had to stop when the last member of the procession was on stage. It is of course possible that some other music was used in its place, but no information has survived to corroborate this.[38] The play’s reviews do not mention any music. As it was a new play, however, they did discuss its content. One aspect that attracted attention was the play’s anti-feminism, which the critic of the Allgemeine Zeitung regarded as positive: ‘The author, as a Finn [sic!], set out to mock feminism, an intention that is in itself noble and deserving of recognition.’[39] The Stage Year Book 1912 wrote: ‘Adolf Paul… brings Solomon in all his glory into his comedy “Die Sprache der Vögel” (Munich, Residenz-theater). It takes its wisdom from the Proverbs of Solomon, and tries to preach it with gay insouciance, but the line of thought is not sufficiently sure and clear, nor are the figures life-like enough.’[40]

Paul wrote to Sibelius before the first night: ‘The Residenztheater – the smaller of the two Court Theatres [in Munich] – is charming. The salon is entirely in the most ornate baroque style – a work of art in its own right, with splendid acoustics. Mozart has stood on the podium in the orchestra pit and conducted his Idomeneo. A pity that you aren’t here. Dear friend, think of me on Sunday.’[41] Sibelius wrote in his diary: ‘Today Adolf Paul’s comedy is premièred in Munich. With my music.’[42]

In Finland, too, the play’s performance was reported. On 17 September the correspondent of the newspaper Hufvudstadsbladet wrote an account that described the content of the play, but did not mention any music.[43] On the day of its publication, Sibelius noted in his diary that the play had been a success: ‘Adolf Paul’s play has received “praise”. He hasn’t said a word to me about anything. Not that I was expecting him to. But it’s strange.’[44]

Later that autumn Sibelius travelled to Berlin, where he met Paul. He wrote in his diary: ‘I heard from Paul that the Wedding March had been well received by the musicians. Still, I observed that his reticence on this subject was a result of jealousy. How human we all are!’[45]

Bird whistles in Vienna

Before the Munich première, Paul had written to Sibelius with the good news that the play was to be performed in Vienna as well, and that autumn it was included in the Hofburgtheater programme; its first night was on 30 November. This production was the first play directed by Albert Heine (1867–1949) at the Burgtheater.

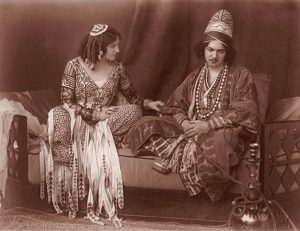

Else Wohlgemuth as Abishag and Alfred Gerasch as Sabud in

The Language of the Birds, Burgtheater, Vienna

(Photo by Archiv Setzer-Tschiedel/Imagno/Getty Images)

Paul was present in Vienna, as he had been in Munich. In the book Profiler he provides a colourful description of the performance: he was told by Heine that forty people – ‘a whole orchestra’ – were sitting playing ‘bird whistles’. Sibelius’s music is not mentioned, although he refers to music in a more general way: ‘ “Places”, shouted the director. I hurried out into my box. The entr’acte was beginning. In Vienna they’re still so old-fashioned, they still have such things! But they’re right! It draws the audience’s thoughts away from their everyday lives, turns their attention to what is to come, and keeps them in the right frame of mind between the acts. In the Burgtheater the orchestra cannot be seen. You can only see the conductor near the prompter’s cubby hole. He stands there directing his underground forces, stirs up something mysterious down there with the baton in his right hand, and sprinkles a little salt and pepper here and there with his left. The Burgtheater conductor, Novotny, was undeniably a comedy in his own right. The première went splendidly…’[46] The reviews ignored the music, although they pointed out the influence of Strindberg and the play’s anti-feminist message.

‘Conductors are idiots’

In January 1912 Sibelius wrote to Paul with some irritation: ‘Old chap… so far I haven’t heard anything about my music for your play. This music that cost me so much artistic effort. Breitkopf wrote – very surprised – that the music had been returned to them, even though they had sent it away as soon as they received the telegram. When I had the great honour of spending some time with Tali [Paul’s wife Natalie, whom Sibelius visited in Berlin the previous October], she said a lot about the play but not a word about the fate of the music. You yourself haven’t given any hint of how the premières went, or whether you used my music, which – even if it didn’t live up to your expectations – can’t be cast ungratefully aside. Breitkopf don’t own the rights to it. The parts were just copied out for a small fee. I haven’t received anything in respect of that, nor do I want it. I can see clearly that there’s a fly in the ointment. But we’re such a pair of old foxes that we can enjoy being angry.’[47]

Paul replied: ‘I have mentioned in my letter [referred letter missing] that, both times, Breitkopf has caused trouble and delay, and was the reason for the dispute in Vienna. Your music is very beautiful and, come what may, I don’t want to be without it at the next première. That’s why I asked you for a piano reduction, so I can play it at rehearsals. It’s incredible how theatre conductors are such idiots!’[48] He repeated his request in March, and in a letter dated 10 March Sibelius promised to make the reduction, referring to it again on 29 May, but probably did not get around to doing so: at least, no such piano reduction has been found.[49]

More performances in German, from Prague to Hamburg

In his letter dated 23 January 1912 Paul tells Sibelius that Georg Müller, the publisher of Paul’s plays, had given strict instructions that every performance contract for The Language of the Birds should stipulate that Sibelius’s music should be included. He mentioned that it would be performed the following season in both Hamburg and Berlin – although nothing came of these plans.

On the other hand, in Vienna performances continued, and the Burgtheater also took The Language of the Birds on tour to Prague and Budapest, as well as performing it in Vienna to mark Paul’s fiftieth birthday in 1913. No records have survived of any performances of The Language of the Birds in Berlin, but it was staged at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg in 1918 (first night 25 May). Paul wrote to Sibelius: ‘Tonight The Language of the Birds will have its première at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg, with your music. I can’t be there as I am ill.’[50] Nonetheless, the archive material at the Hamburg Deutsches Schauspielhaus, including the poster advertising the performance, makes no mention of music.[51] Therefore, despite Paul’s claim, Sibelius’s music was not used in this production either.

The play was programmed again in 1925 at the Residenztheater in Munich, and then at the Burgtheater in Vienna in 1927 (eight performances in September/October, directed by Albert Heine), together with the unfinished drama Esther by Franz Grillparzer (1791–1892). No information exists about music for these performances.

Arthur Travers-Borgström’s English translation

In the autumn of 1921 Paul wrote to Sibelius: ‘Did you know that Arthur Borgström has translated The Language of the Birds quite brilliantly into English; he’s received the most ample praise in London and is now working on getting it performed there with your music. Perhaps we’ll have an English première together this winter.’[52]

Arthur Travers-Borgström (1859–1927)

Photo: Rembrandt. CC BY 4.0

Arthur Travers-Borgström (1859–1927) was acquainted with both Paul and Sibelius. On his father’s side he came from a prosperous Helsinki family of industrialists and traders, and his mother, Alice Travers, came from a family of English merchants.[53] In addition to his business activities, he wrote poems under the pseudonym Vagabond.

Borgström often made large sums of money available to help Sibelius out of his various financial predicaments. To express his thanks Sibelius made a setting of Borgström’s poem Hymn to Thaïs for voice and piano in 1909, which he later dedicated to Aulikki Rautavaara.

Adolf Paul, too, often asked Borgström for financial help, as his correspondence with Sibelius reveals: ‘If it wasn’t for our good friend Arthur Borgström, I would have gone under long ago.’[54]

Borgström’s translation was published in 1922. The edition also contains an introduction by the author and travel writer Henry C. Shelley, in which he discusses Paul’s life and works as well as the performance history and reception of The Language of the Birds. The text contains some errors (for example claiming that the first performance took place in Vienna) that have been repeated elsewhere. He does, however, allude to Sibelius’s incidental music: even the title page mentions ‘Scenic Music by Sibelius’.

At that time Travers-Borgström was in England and gave financial support to attempts to have Paul’s play performed there with Sibelius’s music. Not only did Borgström help with translating, publishing and championing Paul’s play in England, but he even suggested putting him forward for a Nobel Prize, to which end he encouraged Paul to have how works translated into Swedish.[55]

More music for the play

The English première that Paul had envisaged in his letter from the autumn of 1921 did not in fact take place that winter. In October of the following year, Sibelius wrote in his diary that Paul wanted more music for the play. The request was probably made via Borgström, who was then in Finland and had recently met up with Sibelius. ‘A short prelude to be played when the curtain has gone up, leading to the twittering of birds – and, as soon as the curtain falls, an interlude between Acts I and II. A prelude to Act III, and a shortened version of the Wedding March – these are Paul’s wishes.’[56]

Sibelius replied to Paul that he would write the music as requested, but not until the spring.[57] That autumn Sibelius was busy with his Sixth Symphony, on which he worked intensively between October and the following February.[58]

In December Paul told Sibelius that, according to Borgström, the play had been accepted for performance in London and Birmingham. He asked him to hurry up with the music, as ‘they’re only doing the play on account of your music’.[59] The early arrival of the music would have increased the likelihood of a performance in the Birmingham spring season. In another letter Paul commented: ‘It’s good of you to write the bird sounds! Thank you, Janne! If you do it soon, we can have it for the spring season in Birmingham, and you’ll get the payment that you have long deserved but not yet received.’[60] This once again indicates that the music had never been performed together with the play.

Music from Belshazzar’s Feast

From the beginning of 1923 onwards, Paul kept Sibelius up to date concerning the performance situation and the use of his music. Breitkopf had not answered Paul’s letters in which he asked for the material to be sent to England; nor indeed had they sent it. Paul asked Sibelius to use his influence: ‘Can’t you give them a poke in the ribs? Otherwise my play won’t be performed in Birmingham.’[61]

As Sibelius was busy with the Sixth Symphony, he probably did not have time to concern himself with Paul’s request. The symphony’s première took place on 19 February 1923, and six days later Sibelius and Aino set off for an extensive foreign tour to Stockholm, Rome and Gothenburg. In early March they visited Adolf and Natalie Paul in Berlin, en route to Rome.[62] According to Tawaststjerna, during this visit Sibelius suggested that the music he already composed for Hjalmar Procopé’s Belshazzar’s Feast could be used for the Birmingham performance of The Language of the Birds.[63]

As early as 1920 it had been agreed with Lienau, publisher of the Belshazzar’s Feast music, that it could be used in England in conjunction with Paul’s play. [64] Evidently Sibelius had been contacted about this while the translation of the play into English was still at the planning stage. In a letter to Rome Paul told Sibelius that Lienau had sent the music. ‘It’s brilliant and very suitable or – would it be alright with Hj[almar] P[rocopé]? Will he object? The oriental march sounds as if it’s tailor-made for Abishag’s wedding procession.’[65]

The first performance in English, in Birmingham

The play’s first English-language performance took place at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre on 31 March 1923, and it was given fifteen times over a two-week period. It was directed by H. K. Ayliff, who also played the role of Solomon. The journal The Stage praised the stage design by Paul Shelving (1888–1968): ‘Special costumes and stage decorations have been designed by Mr. Paul Shelving. On the scenic side there is much splendour. The scenes, of course, have oriental richness of colouring. The wedding procession is most impressive’, and on the subject of music observed: ‘For the original performance Sibelius composed incidental music, but this is not used for the present revival in this country. The music is nevertheless most appropriate, and is ably conducted, by Mr. Harold Mills. It is as follows:– Overture, “Abu Hassan” (Weber), love song and dance (Rutland Boughton), Hymn to the Sun (Rimski-Korsakov), and “Il Seraglio” (Mozart).’[66]

Movements from Belshazzar’s Feast with new titles

Even though the Birmingham performances did not use Sibelius’s Belshazzar’s Feast music, Paul still wrote to the composer afterwards regarding the adaptation of the score for possible future performances in England:

I spoke on the telephone to Lienau about the music and he promised to deal with it as soon as possible. We can retain the same order in the score and parts if we play the Oriental March [Op. 51 No. 1] as an overture to the play, immediately followed by Solitude [Op. 51 No. 2] (‘Solomon’s question’). Then the Nocturne [Op. 51 No. 3] (here: ‘Sabud’) would be used as a prelude for Act II, and for the Act III the dance [Op. 51 No. 4] (‘Abishag’s Triumph’). And the march can be repeated in Act III for the wedding procession. Would that be acceptable? The main thing just now is for Lienau to get the piano arrangement on the market in England. He can sell a lot of them.[67]

No version of the piano transcription of Belshazzar’s Feast with different titles has been found.

Other performances and planned performances in England

The correspondence between Paul and Sibelius also refers to a performance of the play in London in 1923. Paul wrote to Sibelius: ‘Shelley wrote that the director of the theatre in London had asked him to reserve your new music for the London première.’[68] This shows that Paul was still hoping to receive the new musical numbers that Sibelius had previously promised to compose – but, despite the gentle reminder, Sibelius still did not deliver any. Paul then wrote to him that, notwithstanding the success of the Birmingham production, there would be no further performances in England.[69] But a couple of months later the situation had changed: ‘Lienau has sent your music [Belshazzar’s Feast] to London for my play, Borgström writes. He can sell a lot of copies of the piano arrangement there. The London première will be in the autumn.’[70]

The correspondence between Sibelius and Paul does not disclose which of London’s many theatres was to host the planned performance, but in the press it was reported that at the projected Playbox Theatre: ‘Plays are to be produced in series of three or four, and nearly all the plays in these series will be by well-known British playwrights, and will be seen for the first time in this country. In each series there will probably be one foreign play… Among the succeeding foreign plays will be “L’Annonce fait à Marie” by Paul Claudel; “Die Sprache der Vögel” by Adolf Paul with music by Sibelius; and (it is hoped) “Masse Mensch”, a drama of mankind, by Ernst Toller, one of the leaders of Communists.’[71] The plays were put on by the Reandean Company, managed by Basil Dean (1888–1978), and their matinés were held at St Martin’s Theatre, now best known as the venue for Agatha Christie’s Mousetrap. In the end, however, this projected performance of The Language of the Birds came to nothing.

In 1925 Paul complained to Sibelius that Borgström had not answered his communications.[72] But by that time Borgström had fallen on hard times, and was unable to help either with getting the play performed in England or with other projects. He died eighteen months later, in early 1927.

The Language of the Birds was not performed in London until 1928, at a small and unassuming venue. The first night was on 21 March at the Playroom 6 theatre in New Compton Street, directed and designed by Horatio Taylor, with Charles Maunsell as Solomon, Noel Dixon as Sabud and Elisabeth Addyman as Abishag. The reviews did not mention music and it is likely that the limited size of the venue meant that none was used. This production is not mentioned in the correspondence between Paul and Sibelius. If Sibelius had made a piano version of the Wedding March – which Paul had requested as early as 1912 – that might have been suitable for inclusion.

Tawaststjerna tells us that the play was performed in Liverpool without any music, but that the performance was a ‘complete fiasco’. [73] As there is no information to corroborate this but Tawaststjerna does not mention the Birmingham performance, he may have confused the two cities.

In an article from 1947, Ralph W. Wood claims that Paul’s play and Sibelius’s music had indeed been performed together, but he does not mention where any such performances took place: ‘It is a subtle, witty, urbane version of an episode in the life of King Solomon and has earned its author comparisons with Bernard Shaw as well as Strindberg. It was first performed in at the Burgtheater, Vienna, and subsequently seen at Prague and Buda-Pesth. The music, published without opus number, is quite unknown in concert-halls, but was considered an integral factor in the play’s success on stage. A dramatic critic found it “charming”.’[74] Among Wood’s sources was Shelley’s introduction to the play’s English translation, which wrongly states that the world première took place in Vienna rather than Munich. Wood also states incorrectly that the music had been published. His suggestion not only that the music and play had been performed together but also that a theatre critic had commented on it is odd, as I have been unable to trace any performances at all that used Sibelius’s music.

Film

In 1930 Paul told Sibelius: ‘Now I’m in negotiations about making a film of The Language of the Birds. That’s the last lifeline I have. If anything comes of it, it will be on the condition that all of the music is written by you, and is handsomely rewarded.’[75] Theoretically a film would have been quite possible, as Paul had written a number of film scripts and, back in 1919, had also tried to persuade Sibelius to write some film music for him.[76] Despite the popularity of Oriental themes on film at that time, however, the screen version of Paul’s Language of the Birds never became a reality.

The 1930s: Sweden and Palestine

In 1930 Paul wrote that a contract had been signed with Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern in Stockholm, and that The Language of the Birds was to be included in the following season’s programme.[77] No trace of this performance is found in the theatre’s programme archive, but the play was translated into Swedish (the translation exists in manuscript only and was never performed).[78]

In 1937 Paul wrote to Sibelius that he had received a request from the Habima Theatre in Tel Aviv, Palestine, to perform the play, but that he had turned it down because it came from Leopold Jessner (1878–1945), with whom Paul had previously had bad experiences.[79] These experiences seem to have concerned Jessner’s work as a theatre and stage director in Hamburg, Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) and Berlin, before 1933. During Jessner’s time in Hamburg three of Paul’s plays were performed: Die Teufelskirche, Blauer Dunst and Die Triumph der Pompadour (The Triumph of the Pompadours). Jessner stayed in Tel Aviv for only a short time, and then moved to Hollywood; the Habima Theatre later became the Israeli National Theatre.

Neither a wedding nor a Wedding March

Despite Paul’s above-mentioned letter to his publisher Müller insisting on the use of Sibelius’s music at every performance of The Language of the Birds, it has in fact never been performed in its rightful place in the play, even though some of the theatres in question had orchestras that played (for example) interludes. The music remained unpublished and without opus number. It is perhaps indicative of the fate of Sibelius’s Wedding March that at the end of Paul’s play there is actually no wedding, as the bride beats a hasty retreat.

The Wedding March remained unplayed until 1983, when the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen made a radio recording of it. Its first commercial recording came from the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra under Neeme Järvi in 1990 (BIS-502). A publishing contract was agreed between the Sibelius family and Edition Fazer (now Fennica Gehrman) in 1994, and the score and parts appeared in 1997.

The brevity of Sibelius’s piece may seem surprising, but Paul’s original commission was for one lasting five minutes. Its use of the woodwind corresponds to Paul’s wish for birdsong but it is, so to speak, written into the march. Sibelius omitted the violins entirely from the theatre version that he mentioned both to Paul and to Breitkopf & Härtel, asking instead for the lower strings to be used, presumably to emphasize the register used by the ‘birds’ .

On the other hand, the play’s Oriental theme is not particularly to the fore, either melodically or harmonically. Of the two options he mentioned when composing the work, Sibelius apparently chose the one that was not particularly Eastern. Only the percussion – according to Paul’s text cymbals – try to create an Oriental atmosphere, as in Sibelius’s earlier music for Belshazzar’s Feast. The tempo marking, Allegro, ma moderato e con grandezza, emphasizes the march’s festive, noble character. At the end of the piece, fanfare-like trumpets portray the arrival of the wedding procession.

In the sleeve notes for the first recording Andrew Barnett mentions the stylistic affinities between the Wedding March and At the Draw-bridge, third movement of Scènes historiques II, Op. 66, which was composed shortly afterwards.[80] In the introduction to the published score, Veijo Murtomäki points out similarities with other later works as well: ‘woodwind arabesques based on parallel thirds [,] point forward in Sibelius’s stylistic development to The Oceanides, the music for The Tempest and even Tapiola.’[81]

Because Sibelius wrote the Wedding March for large orchestra, Breitkopf & Härtel’s assessment that it was only suitable for use in the context of the play must have come as a disappointment, especially bearing in mind the publisher’s earlier rejection of his music for The Lizard.

Compared with earlier theatre scores that Sibelius later revised for concert use either independently (Valse triste, Scene with Cranes) or as orchestral suites (King Christian II, Pelléas et Mélisande, Belshazzar’s Feast, Swanwhite), he proceeded in reverse order: first of all he wrote the Wedding March for large orchestra, then reduced the scoring to make a theatre version for Adolf Paul’s play.

Conclusions: Paulini and Sibellini

There are many letters from Sibelius to Paul – and even more from Paul to Sibelius – about the Wedding March. At one point Sibelius suggested to Paul, presumably in jest, that they should collaborate on an operetta: ‘Aren’t you interested in an operetta? Using false, i.e. fictitious names. Paulini and Sibellini. Paul Giovanni Paulini and Adolfo Sibellini.’[82]

The Wedding March was at first a tricky task for Sibelius – one in which many other people had a stake: Paul (who commissioned it), the Munich theatre director von Seidel (responsible for the performance), probably also Albert Steinrück (director of the play), plus Sibelius’s publisher Breitkopf & Härtel and Paul’s, Georg Müller. Despite being only a few minutes long, this piece caused a lot of headaches and work.

In England, too, a number of people were championing Paul, among them Arthur Travers-Borgström and Henry C. Shelley, resulting in some organizational confusion. This may have been why Sibelius lost interest in composing any additional music for the play, especially after Breitkopf & Härtel’s rejection of the Wedding March.

The letters reveal that, despite his annoyance, Sibelius remained patient in the face of Paul’s repeated requests for additional music, and explored the possibility of using the music he had previously composed for Belshazzar’s Feast; Paul (who had studied music and had even composed music for his own play Blauer Dunst, and therefore had a clear vision of how to use music in the theatre) had suggested renaming the movements so they could be used for his play too. Nonetheless, the first English performance in Birmingham used Oriental-style music by other composers, and the Belshazzar’s Feast score has never been used at a performance of The Language of the Birds.

And what did Sibelius think of his own Wedding March? After completing it he wrote in his diary: ‘The style of this composition! Will it stand the test of time? Subtle, but – I think – impractical, at least in the conventional sense!’[83] A few weeks later he continued: ‘I’m slightly embarrassed about all this business with Paul’s theatre music. But – still, the music is genuine. It may not be amazing or interesting, or whatever, in the style of modern commissioned stuff. But it’s natural and “zweckmässig” [appropriately] scored. And it’s not without poetry.’[84]

© Eija Kurki 2019

Eija Kurki D. Phil. published her dissertation Satua, kuolemaa ja eksotiikkaa. Jean Sibeliuksen vuosisadan alun näyttämömusiikkiteokset (Fairy-tale, Death and Exoticism. Jean Sibelius’s Theatre Music from the Beginning of the 20th Century) in 1997. She has written numerous articles in various specialist publications both in Finland and internationally (e.g. Sibelius Studies, Cambridge University Press 2001). This is the first ever large-scale article about Sibelius’s music for Paul’s play The Language of the Birds.

English version published in Sibelius One Magazine, July 2019. Translation: Sibelius One.

Sources:

Aaltonen, Esko 1984 (1947): Entisajan Forssaa ja sen väkeä I. Kolmas painos. Forssan Kustannus KY.

Barnett, Andrew 1990: Wedding March from ‘The Language of the Birds’ in the booklet for BIS-502. BIS Records, Åkersberga

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery 1986: Exhibition Catalogue. Paul Shelving (1888–1968) Stage Designer. 7 June–27 July 1986. Edited and catalogued by Tessa Sidey.

Boyden, Matthew 1999: Richard Strauss. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. London.

Burgtheater 1776–1976: Band I–II. Österreichischer Bundestheaterverband.

Dahlström, Fabian 2003: Jean Sibelius. Thematisch-Bibliographisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke. Wiesbaden-Leipzig-Paris. Breitkopf & Härtel.

Dahlström, Fabian (ed.) 2016: Din tillgivne ovän. Korrespondensen mellan Jean Sibelius och Adolf Paul 1889–1943. Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland. Helsingfors.

Ginzberg, Louis 1909 (2017): Legends of the Jews. Translated from the German manuscript by Henrietta Szold. Volumes 1–4. Global Grey 2017. Globalgreybook.com.

Heymann, Margret 2014: ‘Das Leben ist eine Rutschbahn…’ Albert Steinrück. Eine Biographie des Schauspielers, Malers und Bohemiens [1872–1929]. Vorwerk 8. Berlin.

Huesmann, Heinrich 1983: Welttheater Reinhardt. Prestel-Verlag München.

Kilpeläinen, Kari 1991a: The Jean Sibelius Musical Manuscripts at Helsinki University Library. A complete catalogue. Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden-Leipzig-Paris.

Kilpeläinen, Kari 1991b: Tutkielmia Jean Sibeliuksen käsikirjoituksista. Studia Musicologica Universitatis Helsingiensis 3. Helsingin Yliopiston Musiikkitieteen laitos.

Kindermann, Heinz 1968: Theatergeschichte Europas. VIII Band. Otto Müller Verlag. Salzburg.

Kuka kukin oli 1961: Who was who in Finland 1900–1961. Henkilötietoja 1900-luvulla kuolleista julkisuuden suomalaisista. Otava. Helsinki.

Kungliga Dramatiska Teaterns Repertoar 1908–. Dramatens Arkiv och Bibliotek. Rollboken. www.dramaten.se.

Lüchou, Marianne (ed.) 1977: Svenska Teatern i Helsingfors. Repertoar, Styrelser och teaterchefer, Konstnärlig personal 1860–1975. Stiftelsen för Svenska Teatern i Helsingfors.

Matthews, Bache 1924: A History of the Birmingham Repertory Theatre. London. Chatto & Windus.

Murtomäki, Veijo 1997: ‘Jean Sibelius: Wedding March’ (English translation by Andrew Bentley) in Jean Sibelius: Wedding March for orchestra 1911. Score. Edition Fazer.

Paul, Adolf 1911: Die Sprache der Vögel. Komödie in vier Akten. München bei Georg Müller.

Paul, Adolf 1922: The Language of the Birds. A comedy by Adolf Paul. Only authorised English translation by Arthur Travis-Borgstroem, scenic music by Jean Sibelius; introduction by Henry C. Shelley. London. Montgomery.

Paul, Adolf 1937: Profiler. Minnen av stora personligheter. Söderström & C:o Förlagsaktiebolag. Helsingfors.

Rask, Hedvig: Adolf Paul – en litterär översikt, pp. 49–60. ‘Din tillgivne ovän. Korrespondensen mellan Jean Sibelius och Adolf Paul 1889–1943’.

Sibelius, Jean 1911 (manuscript): Die Sprache der Vögel / Schauspiel von Adolf Paul. op. 64. Hochzeitzug. Tonstück für Orchester. UBHels 0938. Helsinki University Library.

Sibelius, Jean 1911 (manuscript, sketch): Die Sprache der Vögel. HUL 0939. Helsinki University Library.

Sibelius, Jean 1997: Wedding March from the play ‘Die Sprache der Vögel’ by Adolf Paul for orchestra 1911. Score. Edition Fazer.

Sibelius, Jean 2005: Dagbok 1909–1944, ed. Fabian Dahlström, Skrifter utgivna av Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland 681, Helsingfors och Stockholm: SLS & Bokfölaget Atlantis.

Tawaststjerna, Erik 1971 (1989): Sibelius 3. Otava. Helsinki.

Tawaststjerna, Erik 1988: Sibelius 5. Otava. Helsinki

Trewin, J. C. 1963: The Birmingham Repertory Theatre 1913–1963. Barrie and Rockliff. London.

Wearing, J. P. 2014: The London Stage 1920–1929. A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Wood, Ralph W. 1947: ‘The Miscellaneous Orchestral and Theatre Music’, pp. 38–90 in Sibelius. A Symposium, ed. Gerald Abraham. Lindsay Drummond Limited. London.

[1] Aaltonen 1984 (1947), pp. 114–115

[2] Rask 2016

[3] Lüchou 1977, pp. 88–89

[4] Paul to Sibelius, 16 September 1903: ‘Skriv för fanden violinsolot, kort och bussigt – du kan och ingen annan…

Du skrifver det nog på en halvtimme.’

[5] Paul to Sibelius, 9 May 1919 and 24 January 1921

[6] Dahlström 2016, pp. 34–35

[7] Ginzberg 1909, p. 967

[8] Boyden 1999, p. 164

[9] Tawaststjerna 1971 (1989), p. 235

[10] Paul to Sibelius, 22 March 1911: ‘schreibst du kurze buechnennotiz zu meinem neuen stuecke auffuehrung hoftheater muenchen brief = adolf’

[11] Paul to Sibelius, before April 1911: ‘Käre Janne, Gör mig den stora tjensten att skrifva musik till mitt nya stycke. Det kommer mycket snart fram vid hofteatern i München och att döma af hur kåta de äro på det, och här i Hamburg och annorstädes. Du kan alltså förtjena på det. Så snart det är tryckt sänder jag dig ett exemplar. Det heter ”Foglarnes språk”. Salomo är hufvudpersonen och Abisag från Sunem hjeltinnan! (Du vet hon som lades hos den gamle Kung David för att värma de slocknade lifsandarne och som sedan Salomo gaf åt sin vän Sabud till fru). Bara ett nummer, orientaliskt, trummor, harpor, cymbal, flöjter och annat jobb. Höres först ur det inre af palatset der hon smyckas till brud, – så kommer bröllopståget närmare – (stor stass af eunucker och hoftjenstefolk) och in på scenen – högst 5 minuter tar det hela.’

[12] Paul to Sibelius, 19 April 1911: ‘Då vi på titelbladet till stycket få lof att annonsera hvar musiken får köpas, och Breitkopfs väl åtar sig att ”mångfaldiga” och sälja den, hoppas jag du har intet emot att vi sätta dit ”Musik von Jéan Sibelius bei Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig. Partitur und Stimmen daselbst”. Jag skriver och frågar dem, för formens skull också, och skall be dem ta ordentligt betalt af direktörerna.’ / ‘Excellenzen von Speydel i München som är direktör för teatrarne der var högst charmerad öfver att du skrifver musiken…’

[13] Sibelius to Paul, 23 April 1911: ‘Sänd med det första ditt nya mästerverk. Så jag vet huru mycket musik som skall levereras. Samt håll öga på B et H.’

[14] Sibelius to Breitkopf & Härtel, 23 April 1911, quoted in Dahlström 2003, p. 52: ‘Ich habe gar keine Ahnung wie viel ich zu komponieren habe, möchte aber sehr gern d. Paul behilflich sein.’

[15] Paul to Sibelius, 16 May 1911: ‘Det är egentligen bröllopståget i tredje akten och så slutet som behöver musik. Och – om du finner kanske ”foglalätena” också.’

[16] Paul 1922, pp. 62–63; Paul 1911, pp. 75–76

[17] Paul 1922, pp. 70–71; Paul 1911, pp. 87–88

[18] Paul 1922, p. 13; Paul 1911, p. 1

[19] Paul to Sibelius, 16 May 1911: ‘På titelbladen har vi tryckt att musiken av Janne fås hos Breitkopf & Härtel i Leipzig. De voro med om det och skrefvo att du nämt om det i bref till dem.’

[20] Sibelius to Paul, 26 May 1911: ‘Det blir nog bra litet musik – endast en marsch. Jag tänker därför taga endast blås- och slaginstrument. Fågelqvittret skulle jag gärnä göra men äfven det fölle ur ramen.’

[21] Tawaststjerna 1971 (1989), pp. 269–270

[22] Diary, 4 August 1911

[23] Sibelius to Paul, 15 July 1911: ‘En marsch, orientalisk, kall och vild, festlig och brillant. En åter, den jag stannade för, festlig, antik och varm. Poetisk med andra ord. Jag tror det är den rätta. Salomos hela syn på tingen är ju varm.’

[24] Paul to Sibelius, 25 July 1911” ‘så skicka hit båda två…’

[25] Sibelius to Breitkopf & Härtel, 5 August 1911, quoted in Dahlström 2003, p. 528: ‘Hiermit habe ich die Ehre Ihnen zur Ansicht meine Composition ”Hochzeitszug” für Orchester, Op. 64, zu überreichen. In vereinfachter Besetzung wird das Stück als Musik zu Adolf Pauls Komoedie ”Die Sprache d. Vögel” angewendet.’

[26] Sibelius to Paul, 5 August 1911: ‘På scenen spelas denna komposition af sexton man, de äro: 2 Flauti, 1 Oboe, 2 clarinett, 1 Basclarinet, 1 trumpet, 1 Basun, 2 Altvioliner, 2 Celli, 1 Bass, (Triangel och liten Trumma), (Stortrumma och Tamburin), (Pukor). Ingesamt 16 man” Detta har jag anmärkt på partituren.’

[27] ‘Die violinen werden nur bei starker Besetzung gespielt’

[28] manuscript HUL 0939; see Kilpeläinen 1991a, p. 244

[29] Diary, 23 August 1911: ‘Intet från B. et H. Något därbakom?! Det är nu ej ”Hela verlden” om de, d.v.s. B et H, ej vilja ha asken! ”Så svek mig ej min goda lukt”-principen främmande för dem i så fall.’

[30] Sibelius to Paul, 29 August 1911

[31] Dahlström 2003, p. 528

[32] Diary, 28 August 1911: ‘Jobs-poster från B. et H. De vilja ej ha ”Hochzeitzug”. Skall försöka klara skifvan med nå’n annan. – ”Si male nunc et olim sic erit”! Trodde aldrig att detta kunde hända mig. Nu gäller Kamp!’

[33] Sibelius to Paul, 29 August 1911: ‘Jag skall nog hämnas på B et H. Var lugn! Eheru på ett något ”finare” sätt än de äro vana vid.’

[34] Paul Klengel to Breitkopf & Härtel, 28 August 1909, quoted in Dahlström 2003, p. 27: ‘Die begleitende Musik zu Ödlan […] ist nur in direktem Zusammenhang mit den Vorgängen auf der Bühne gedacht und würde ohne diese kaum verständlich sein und auch kaum Interesse erwecken.’

[35] Kilpeläinen 1991b, pp. 196–197

[36] ‘in alter Freundschaft gewidmet’

[37] Paul to Sibelius, 7 September 1911: ‘Hjertligt tack för din vackra musik som jag hörde första gången i dag. Vi har bara 40 man i festtåget då sçenen är liten, få alltså ”afbryta” musiken – annars sku vi få ta in flere hundra statister och det går inte.’

[38] No materials pertaining to this performance (posters, photographs) have survived. Information provided to the present author by Babette Angelaeas and Kim Heydeck, Deutsches Theatermuseum in Munich, 18 June, 2019

[39] Allgemeine Zeitung, 23 September 1911: ‘Dem Autor als Finnen lag daran, den Feminismus zu verspotten, und schon diese Absicht ist edel und verdient Anerkennung.’

[40] The Stage Year Book 1912, p. 71

[41] Paul to Sibelius, 7 September 1911: ‘Residenzteatern – den mindre af de båda hofteatrarne –är förtjusande. Salongen helt i rikaste barock – ett konstverk i och för sig, akustiken glänsande. I orkestern har Mozart stått vid dirigentpulpeten och dirigerat sin Idomeneo. Skada att du inte är här. Käre vän, tänk på mig om söndag.’

[42] Diary, 9 September 1911 (one day before the première): ‘I dag premier i München af Adolf Paul’s komedie. Med min musik.’

[43] Hufvudstadsbladet, 17 September 1911. Litteratur och Konst. ‘Adolf Pauls skådespel Fåglarnas språk’

[44] Diary, 17 September 1911: ‘Adolf Pauls skådespel får ”beröm”. Mig underrättar han ej med ett ord om nånting. Icke därför att jag väntar mig något. Men det är säreget.’

[45] Diary, 31 October 1911: ‘Hörde af Paul att Hochzeitzug hade haft framgång hos musikerna. Jag märkte förresten på honom att hans tystlåtenhet i denna sak härledde sig af jalousie. Huru menskliga äro vi ej alla!’

[46] Paul 1937, pp. 143–153: ‘Har 40 man sittande med fågelpiporna – en hel orkester! ’ / ‘Plats på scenen! skrek regissören. Jag skyndade mig ut i min loge. Mellanaktsmusiken började. Man är ännu så gammalmodig i Wien, att man har den kvar! Och man gör rätt i det! Den får publikens tankar bort från det dagliga livet, riktar dess uppmärksamhet på vad komma skall och håller den i stämning under mellanakterna. I Burgtheatern är orkestern osynlig. Endast kapellmästaren ser man framme vid sufflörsluckan. Han står där och dirigerar sina underjordiska makter, rör ihop någonting hemlighetsfullt med högra handens taktpinne där nere och strör litet peppar och salt då och då med den vänstra. Burgteaterns kapellmästare, Novotny, var onekligen en komedi för sig. Premiären gick briljant … ’

[47] Sibelius to Paul, 18 January 1912: ‘Gamle gosse, Tills dato har jag ej fått höra nån’ting om min musik till ditt stycke. Denna musik, som kostat mig så mycken konstnärlig möda. Breitkopfs skrefvo – fulla af förundran – att de erhållit noterna returnerade eheru de omedelbart afsände notmaterialet då telegrammet ingått. Då jag hade det stora nöjet att vara med Tali, berättade hon mycket om stycket men nämnde icke ett ord om musikens öde. Själf har Du ej med ett ord låtit mig veta huru denna premiären aflupit samt om du begagnat dig af min musik, som – låt så vara att den måhända ej motsvarar dina förväntningar – dock icke kan så där sans facon slängas undan. Breitkopf äga ej stycket. Noterna erhållas endast copierade emot ett litet honorar. Jag har intet erhållit för detta arbete och vill det ej heller. Att det varit något smolk i mjölken märker jag granneliga. Men – vi äro ju båda så pass gamla räfvar att vi kunna njuta af att vara arga

[48] Paul to Sibelius, 23 January 1912: ‘Att Breitkopfs båda gångerna krånglat och sölat och voro orsak till bråket i Wien har jag omnämnt i mitt brev. Din musik är herrligt vacker och jag vill ej på vilkor gå miste om den vid nästä premiere. Derför bad jag dig ge mig en pianoskizz af den så att jag kan få spela den på repetitionerna. Det är alldeles otroligt hvad teatrarnas kapellmästare äro idiotiska

[49] Dahlström 2016, p. 36

[50] Paul to Sibelius, (wrongly dated) [June 1918]: ‘I qväll har Die Sprache der Vögel premiere, Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg med din musik. Jag kan ej fara dit då jag är sjuk.’

[51] Information provided to the present author by Dr Jürgen Neubacher, Staats- und Universitätsbibliotek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky, 13 February 2019

[52] Paul to Sibelius, 12 September 1921: ‘Vet du att Arthur Borgström har öfversatt ”Foglarnes Språk” alldeles brillant till engleska och har fått de mest ampla loford i London och håller nu på att drifva fram den der med din musik. Kanske få vi så en engelsk premiere tillsammans i vinter.’

[53] Kuka kukin oli 1961, p. 56

[54] Paul to Sibelius, 16 December 1921: ‘Hade ej vår vän Arthur Borgström varit hade jag varit under isen för längesedan.’

[55] Paul to Sibelius, 15 April and 22 June 1923

[56] Diary, 14 October 1922: ‘Ett kort förspel som förtonar sedan ridån gått upp och öfvergår till fogelqvittret – och genast ridån faller ett mellanspel mellan 1 och 2 akten. Ett förspel till 3 akten och bröllopståget som förkortas – Detta Paul’s desiderata.’

[57] Sibelius to Paul, 16 October and 9 December 1922

[58] Tawaststjerna 1988, pp. 113–115

[59] Paul to Sibelius, 11 December 1922: ‘då de ju spela stycket bara för din musiks skull’.

[60] Paul to Sibelius, 26 December 1922: ‘Att du gör foglalåten är snällt! Tack Janne! Gör den snart så vi får den till vårsäsongen i Birmingham och du skall få dig en lön som du länge förtjent men ännu ej fått.’

[61] Paul to Sibelius, 11 January 1923: ‘Kan du inte ge dem en Rippenstoss? Annars spela de mig inte i Birmingham.’

[62] Sibelius to Paul, 12 March 1923

[63] Tawaststjerna 1988, p. 132

[64] Sibelius to Lienau, 20 February 1920

[65] Paul to Sibelius, 16 March 1923: ‘Den är brillant och passar utmärkt eller – gör der för Hj[almar] P[rocopé]? Gruffar han inte? Den orientaliska marschen är som vore den gjord för Abisags bröllöpståg.’

[66] The Stage, 5 April 1923, p. 20, ‘Provincial Productions. The Language of the Birds’

[67] Paul to Sibelius, 5 April 1923: ‘Jag talade i telefon med Lienau om musiken och han lofvade genast ta itu med den. Vi kan i partitur och stämmor behålla ordningen om vi gör så att vi spela den orientaliska marchen som förspel till hela stycket och genast anslutande: solituden (”Salomos fråga”). Så kommer som förspel till andra akten ”Nächtliches Lied” (Här ”Sabud”) och till tredje: dansen (”Abisag triumfans”). Och marschen upprepas sedan i Akt III som bröllopståg. Går det så? Hufvudsaken för Lienau är att få ut pianoarrangemanget i England just nu. Han kan sälja kopiöst deraf då.’

[68] Paul to Sibelius, 5 April 1923: ‘Shelley skref att direktören för London teatern bedt honom reservera din nya musik för Londonpremieren.’

[69] Paul to Sibelius, 15 April 1923

[70] Paul to Sibelius, 22 June 1923: ‘Lienau har allt sändt din musik [op. 51] till mitt stycke till London, skref Borgström. Han får nog sälja en mängd af pianoarrangementet der. Premièren i London blir höst.’

[71] The Stage, 22 February 1923. ‘Chit Chat. The Playbox’

[72] Paul to Sibelius, 30 September and 5 October 1925

[73] Tawaststjerna 1988, p. 132, ‘täydellinen fiasko’

[74] Wood 1947, p. 86

[75] Paul to Sibelius, 29 January 1930: ‘Nu förhandlar jag om att göra tonfilm af foglarnes språk. Det är för mig sista rädningsankaret. Blir det af så gör jag till betingelse att hela musiken skall skrivas af dig, och betalas rikligt.’

[76] Paul to Sibelius, 9 May 1919

[77] Paul to Sibelius, 22 October and 1 December 1930

[78] Information provided to the present author by Dag Kronlund. Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern, 15 March 2019.

[79] Paul to Sibelius, 14 May 1937

[80] Barnett 1990

[81] Murtomäki 1997

[82] Sibelius to Paul, 26 May 1911: ‘Är icke Bror lifvad för en operett? Under falskt d.v.s. fingeradt namn. Paulini och Sibellini. Paul Giovanni Paulini och Adolfo Sibellini.’

[83] Diary, 4 August 1911: ‘Är den att hålla på? Subtil, men – som jag tror – opraktisk, åtminstone i gammal bemärkelse!’

[84] Diary, 20 August 1911: ‘Är något generad öfver hela den Paul´ska teatermusiken. Men – nog är denna musik äkta. Låt så vara att den ej är förbluffande, intressant m.m. i denna moderna ”Commis”-stil. Men den är naturlig och ”Zweckmässig”t instrumenterad. Samt saknar ej poesi.’