Jean Sibelius Werke – Series IV (Works for solo instruments with piano) Vol. 6: Works for Violin or Cello and Piano, edited by Anna Pulkkis

SON 621 / €281.41 / 352 pages / ISMN: 979-0-004-80323-3

Click here for further information or to order.

Newly released in the ongoing JSW (Jean Sibelius Werke) critical edition from Breitkopf & Härtel is a volume featuring music for violin (his own instrument) or cello and piano. The present edition contains all the opus-numbered pieces for these combinations except the Violin Concerto, which has already been released in the JSW series (SON 628 Vol. 1A). Even though the majority of works included are short – the exceptions being the Sonatina in E major for violin and Malinconia for cello – the volume is still a substantial release, running to 352 pages.

Violin and Piano

Sibelius wrote extensively for violin/cello and piano during his youth, but the earliest works included here are two pieces, Romance and Perpetuum mobile, that were written in 1890/91 and revised (as Romance and Epilogue) in August 1911. The Romance draws on material from a sonata movement for piano, and thus links back to the music of his student years.

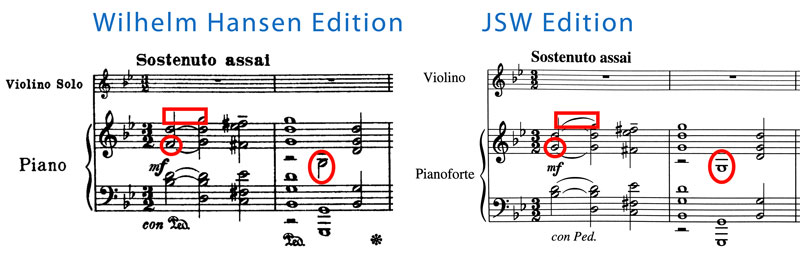

Many of the violin works included here date from the First World War. As the war had isolated Sibelius from the European mainstream, he initially offered Opp. 77–80 to the local publisher Axel Lindgren, who acquired the rights but failed to issue them in print. The rights passed to another Helsinki publisher, Westerlund, and then to Wilhelm Hansen who finally issued them in the early 1920s. Hansen blamed Westerlund for some mistakes in the scores but, whoever was to blame, errors there were, and it is good that these have finally been corrected in the JSW edition. Compare for example the opening bars of Religioso, Op. 78 No. 3, in the Hansen and JSW editions – note in particular the altered harmony in the first chord:

Like his piano music, Sibelius’s violin pieces can present technical challenges, but there are many works here that are well within the capabilities of a reasonably proficient amateur player. Also like with the piano music, sometimes the short pieces were collected into groups for the purposes of publication and/or convenience, for instance Op. 78 (for which Sibelius considered the title Pensées fugitives), Op. 79 and Op. 81. Op. 77 contains just two ‘Ernste Melodien’ (Serious Melodies), a title that is eminently well deserved. The exception is the Op. 80 Sonatina in E major, a three-movement piece lasting some 12 minutes and composed in time for the composer’s fiftieth birthday celebrations in 1915. ‘Dreamed that I was twelve years old and a virtuoso. My childhood sky is full of stars – so many stars’, Sibelius wrote in his diary while working on the piece.

After the wartime pieces we jump forward until the 1920s before Sibelius again started to write for violin and piano. As always he was in financial difficulties and the Novellette, Op. 102, was planned as the first of a set of pieces, although in the end it remained the only one to bear this opus number. Its style is gentler and more ‘romantic’ than the five Danses champêtres from 1924/25, which blend a bucolic character with a degree of acerbity that anticipates the later Opp. 115 and 116 groups. Dating from 1929, these hint at the sort of musical language Sibelius might have used in his Eighth Symphony.

Cello and Piano

The two Serious Melodies, Op. 77, and Four Pieces, Op. 78, are playable by either violin or cello and piano (both versions are included here), which leaves Malinconia, written for Georg and Sigrid Schnéevoigt in 1900, as Sibelius’s only mature piece exclusively for cello and piano. It is a substantial piece, some 12 minutes long in performance. The critical edition reveals that it was shortened by at least six bars a few years later (as much as possible of the ‘missing’ bars is included in the critical comments), with further revisions before publication in 1911.

The present volume, edited by Anna Pulkkis, contains the usual authoritative essay about the music (which is particularly thorough concerning the works’ publication history) and copious editorial notes as well as a number of facsimiles, mostly of manuscripts or sketches but also including and a page of proofs with corrections by Sibelius.

Review by Ian Maxwell & Andrew Barnett

Review copy kindly supplied by Breitkopf & Härtel