Click here to download this article as a pdf file

Sibelius’s ‘Swanwhite’ –

the original incidental music

Eija Kurki

Sketch for Swanwhite made in 1901 by Arthur Sjögren (1874–1951), who worked closely

with Strindberg. Sjögren made the sketch after a meeting with Strindberg and according

to his instructions.[1] Nordiska museets arkiv. CC BY-NC-ND-4.0. Image straightened.

Introduction

The Swedish author August Strindberg (1849–1912) wrote Svanevit (Swanwhite), a symbolic fairy-tale play about love, in 1901 as an engagement present for the young Norwegian actress Harriet Bosse (1878–1961), thirty years his junior, who was to become his third wife that same year. Their marriage was short-lived and officially ended in 1904, although Strindberg still hoped to be reunited with her later. Harriet Bosse was the inspiration for Strindberg’s A Dream Play and Swanwhite. In 1906 she made a guest appearance at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki, playing the role of Mélisande in Maurice Maeterlinck’s symbolist play Pelléas et Mélisande. Jean Sibelius (1865–1957) had composed incidental music for that play, and Harriet Bosse later described the performances as follows: ‘As I lay on my deathbed during the last act, the orchestra played The Death of Mélisande. I was so moved that I cried – at every performance.’[2]

Harriet Bosse made Sibelius’s acquaintance in the context of these performances and, impressed by his music for Pelléas, she suggested to Strindberg that Sibelius should write a score for Swanwhite, which had not yet been performed on stage. Strindberg replied in a letter to Harriet Bosse: ‘Sibelius is welcome to write music for Swanwhite.’[3] The premiere of the play was planned for 1907, in Stockholm, but this proved impossible. Instead, the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki decided to give the premiere of Swanwhite, and commissioned Sibelius to write the music. The first performance both of Strindberg’s play and of Sibelius’s incidental music took place at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki on 8 April 1908.[4]

Swanwhite was directed by the theatre’s head Konni Wetzer. The part of Swanwhite was played by the Swedish actress Lisa Håkansson and the Prince by Gustaf Hjorth. Strindberg sent a postcard to Sibelius, who conducted the music at the premiere, with the following text: ‘Maestro Sibelius! Thank you for the wonderful music you wanted to make for my most beautiful poem! Soon I may have the chance to hear it!’[5] The first performance of Swanwhite was a considerable success. The music Sibelius had written for the play played a major role in its popularity, and it became the second most popular Strindberg play at Helsinki’s Swedish Theatre between 1900 and 1950.

Swanwhite finally received its Swedish premiere at Intima Teatern in Stockholm on 30 October 1908, six months after the Helsinki premiere. Swanwhite was played by the 17-year-old Fanny Falkner, with whom Strindberg was now in love. Bosse, despite Strindberg’s hopes, had refused to remarry him and had declared that she was involved with someone else. Bitterly, Strindberg wrote to Albert Ranft, the director of the Swedish Theatre in Stockholm: ‘This matron [Harriet Bosse], over thirty years old, must not spoil my beautiful poem; and she [Fanny Falkner] must not fail!’[6] Harriet Bosse was never to perform this role that had been written for her.

Apparently Strindberg never heard Sibelius’s incidental music either. For reasons of cost, there was no music at all in the performances at Intima Teatern in Stockholm. Sibelius’s Swanwhite orchestral suite was performed at the Swedish Theatre in Stockholm for the first time in 1914, two years after Strindberg’s death.

Harriet Bosse, 1899 August Strindberg, 1901

Helledaysamlingen (public domain) National Library of Sweden

The main character in Strindberg’s three-act play, the 15-year-old Princess Swanwhite, lives in a medieval fairy-tale castle with her father (the Duke) and wicked Stepmother, who is a witch. The castle is also home to a number of the Stepmother’s fantasy animals such as a peacock. The Stepmother has three girls as servants. When she was small, Swanwhite had been promised in marriage to the Young King of the neighbouring principality. Now the King’s ambassador, the youthful Prince, has arrived to instruct Swanwhite in regal etiquette – but Swanwhite falls in love with the Prince and decides to have him for herself.

The play breathes an air of fairy-tale love in the middle ages. In this respect it is reminiscent of Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande. Behind both of these plays lies the story of Tristan and Isolde – Wagner was, after all, greatly admired by the symbolists. In Maeterlinck’s play Golaud kills Pelléas out of jealousy, and at the end of the play Mélisande dies after giving birth to a daughter. In Strindberg’s text the Prince (who corresponds to Tristan and Pelléas) is drowned at sea, but Swanwhite (Isolde/ Mélisande) brings him back to life with God’s help. Unlike Tristan and Isolde or Pelléas and Mélisande, the young lovers in Swanwhite are united in this world, not the next.

In a letter Strindberg explains that he was influenced by Maeterlinck when writing this play. He also observes: ‘there are princes and princesses everywhere; I have long found the stepmother motif to be a constant feature in fairy-tales; and in such tales we also find dead people coming back to life.’[7]

Sibelius’s Swanwhite music, JS 189 / Op. 54 (1908), contains fourteen musical numbers for small orchestra. The score requires flute, clarinet, two horns, triangle, timpani, organ and strings.

‘Swanwhite’ was the second most popular Strindberg play (after ‘Gustav Vasa’) at Helsinki’s Swedish Theatre at the beginning of the twentieth century, to a large extent because of Sibelius’s music. This picture is from 1921. Photo: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland SLSA 1270.

The Play and the Music

Act I

At the beginning of the first act the Duke, who is about to leave for war, says farewell to his daughter. He gives Swanwhite a magic horn, which she may use to summon her father if she is in danger. He also tells her that the Young King of the neighbouring principality – Swanwhite’s husband-to-be – has sent his Prince to teach Swanwhite the manners that befit a queen. We hear the army’s horn-call, a signal for the Duke to depart.

Swanwhite awaits the arrival of the Prince. This scene (without dialogue) in Strindberg’s play contains indications for stage effects: the wind whistles outside, the peacock shakes its wings and its tail. The recurring note E from the flute and clarinet represents the peacock’s cries, and the transition-like string figurations depict the rosewood blowing in the wind. At this point the characters of Swanwhite and the Prince are depicted in the music. The movement is in ABA form; the violins’ melody with its appoggiaturas represents Swanwhite, and the motif featuring string pizzicati represents the Prince. The themes’ similarity indicates the young couple’s suitability for each other.

The wicked Stepmother and her three servant girls arrive to interrupt the encounter between Swanwhite and the Prince. The Stepmother tells the Prince to go and sleep in the castle tower. Swanwhite’s dead mother flies past the castle in the shape of a swan; the flight of the Swan-Mother is represented musically by an E major chord.

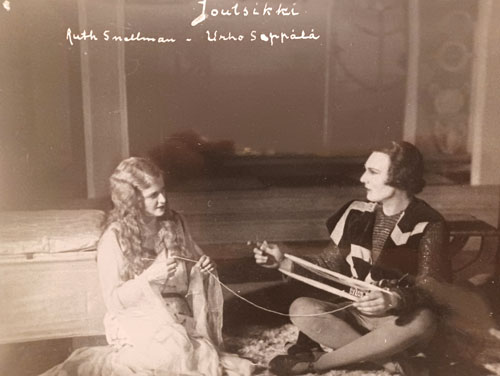

Sibelius’s daughter Ruth Snellman in the role of Swanwhite and Urho Seppälä as the Prince in a 1930 Finnish-language-production of ‘Swanwhite’ at the National Theatre in Helsinki.

Finnish National Theatre Archive, photo: Tyyne Savia.

Act II

Swanwhite’s wicked Stepmother has not allowed her to wash her feet, brush her hair or wear clean clothes. At the beginning of the second act, while Swanwhite is asleep, her Swan-Mother arrives, carrying a magic harp that plays itself. She combs her daughter’s hair, washes her feet and brings her a fresh, white gown. During this scene, too, there is no dialogue but we hear Sibelius’s music. The music consists of rising, arpeggio-like pizzicato figurations from the muted strings. The pizzicato arpeggios imitate the sound of the harp.

Swanwhite’s mother weeps as she washes her daughter’s feet. The flute and clarinet solos at the end of the musical number depict the mother’s moods. The Prince’s Swan-Mother also flies in. In the music we hear once again the E major chord representing a flying swan.

The mothers of Swanwhite and the Prince meet and agree upon the forthcoming union of their children. It becomes apparent from their conversation that the Young King is an evil man, unsuitable to be Swanwhite’s husband. Dawn breaks, and the Swan-Mothers depart. At the same time the table clock chimes three times. The dawn chirping of a robin is depicted by a warbling flute, and the chimes of the clock are represented in Sibelius’s music by three notes from the triangle. The scene without dialogue continues: Swanwhite awakes and notices the change that has befallen her: her feet are clean, her hair is combed and on the bed there is a beautiful white gown. The strings’ pizzicato figurations allude to the sound of the magic harp.

Another scene without dialogue: Swanwhite imagines holding a conversation with the Prince. The strings’ G sharp minor melodic line does not lack a hint of romance.

The Prince arrives to join Swanwhite, but the lovers’ happy conversation soon turns into a quarrel. Swanwhite leaves, and the Prince remains, sad and alone. The Prince’s sorrow is depicted in Sibelius’s music. A dark-toned melody in G minor is based upon a theme which moves in small intervals. The melody is heard first from the clarinet and then from the strings. The music progresses laboriously, reflecting the Prince’s sadness, and this is emphasized by a rhythmic motif from the lower strings.

The Stepmother arrives and offers the Prince the hand of her daughter Magdalena in marriage. As a result of the recent dispute, the Prince decides to accept her in place of Swanwhite and, straight away, they celebrate the wedding. The bride arrives, her face veiled. The theme is a melody that resembles a wedding waltz, but the melancholy key of E flat minor reveals that something is amiss.

The bride’s veil is lifted to reveal – to everybody’s surprise – Swanwhite herself. The young couple go to sleep in bed, with the Prince’s sword virtuously placed between them. The melody that characterizes Swanwhite and the Prince’s bed scene is graceful and charming. The violin melody is accompanied by gentle cello pizzicato motifs that imitate the plucking of a harp. The horns allude to the sound of Swanwhite’s magic horn.

The Stepmother arrives and, finding Swanwhite in bed in place of her daughter Magdalena, snatches the sword from between them and accuses the young people of concealing an impediment to marriage: Swanwhite had, after all, been promised to the Young King. The Stepmother imposes a punishment on them both: Swanwhite’s long hair is to be cut in such a manner that she is ashamed of herself, and the Prince is to be taken back to his native country in chains.

Act III

Before the planned premiere of the play in 1907, Strindberg added some additional text at the beginning of the third act. In this scene Swanwhite’s intended husband, the Young King, arrives to meet her. In his opinion Swanwhite is not remotely attractive, and not at all suitable to be his wife – and so he has no intention of marrying her. Meanwhile the Prince, who had hidden to avoid the Stepmother’s punishment, returns, and Swanwhite runs into his embrace. In the music, a string theme characterized by rising scale motifs is followed by a theme for flute and violins. The flute’s staccato figurations add an element of gentleness which emphasizes the happy reunion of Swanwhite and the Prince. Very similar musical material was later to find a place in Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony.

When he sees the tender scene between Swanwhite and the Prince, the disappointed Young King threatens to burn down the Duke’s castle and kill the Prince. The Prince flees by boat to avoid the Young King’s punishment. Swanwhite blows her magic horn to summon help from her father, the Duke. The central elements of Sibelius’s music at this point are a clarinet solo and the horns’ short signals. Swanwhite blows her own horn, and another horn answers her. The timpani rumble in the background.

The Duke resolves the disputes and decides that Swanwhite and the Prince should be united. The Stepmother too changes for the better: she sheds her snake-like witch costume and becomes a normal person. While sailing to safety, the Prince decides to swim back to Swanwhite, but on the way he is drowned; his dead body is brought to Swanwhite. Here Sibelius’s music stresses the unhappy events of the play, but although the music is characterized by slow, accented quavers, the atmosphere is of consolation rather than gloom.

The final scene of ‘Swanwhite’, production at the Swedish Theatre, Helsinki 1921.

Photo:Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland SLSA 1270

Swanwhite brings the Prince back to life with God’s help. She whispers in the Prince’s ear and, the third time she does so, he comes back to life. The play ends with a scene in which all the characters fall on their knees in gratitude and praise God. The music Sibelius provided here is in C major, and the use of simple thematic material creates a mood of devotion. Just over a week after the first performance, Sibelius added an organ part to the last two numbers in his score.

Conclusion and Orchestral Suite

As we have seen, the incidental music features the fantasy instruments of Strindberg’s fairy-tale – the harp and the magic horn. Sibelius imitates the harp by means of string pizzicati. Princess Swanwhite’s magic horn is heard on numerous occasions in the score, and it appears as a horn duet within the orchestral texture at the point where Swanwhite blows her own horn and is answered by another. In the music we can also hear the fantasy animals of the play: the clarinet and flute imitate the calls of the peacock. Music is heard during much of the pantomime scene in the play. Sibelius wrote the music for the places indicated by Strindberg’s stage directions.

In the autumn of 1908 Sibelius reworked the incidental music into a seven-movement orchestral suite, Op. 54, for concert use. The orchestral suite includes almost all of the material from the original score because Sibelius combined several numbers to form longer movements.[8] In addition the orchestration has been expanded; for example, the suite calls for a harp as well as four horns. In the suite an entire movement is devoted to Swanwhite’s mother’s fantasy creature, the peacock, the rapping of whose beak is rendered musically by the clacking of castanets. It was first performed in Christiania (Oslo) on 8 October 1910, conducted by the composer; on that occasion the second and fifth movements were omitted.

© Eija Kurki 1996/2023

‘Swanwhite’ at the Finnish National Theatre, 1930. On the left Swanwhite (played by Sibelius’s daughter Ruth Snellman), in the middle the Stepmother. Finnish National Theatre Archive, photo: Tyyne Savia.

Eija Kurki D. Phil. published her dissertation Satua, kuolemaa ja eksotiikkaa. Jean Sibeliuksen vuosisadan alun näyttämömusiikkiteokset (Fairy-tale, Death and Exoticism. Jean Sibelius’s Theatre Music from the Beginning of the 20th Century) in 1997. She has written numerous articles in various specialist publications both in Finland and internationally. This article is a revised version of the cover text for BIS’s world premiere recording of the complete Swanwhite score in 1996 and is based on the writer’s Master’s degree in musicology and theatre research at Helsinki University in 1994, ‘August Strindbergin ja Jean Sibeliuksen Joutsikki’ (‘Swanwhite by August Strindberg and Jean Sibelius’). Swanwhite is also discussed in her article ‘Sibelius and the theater: a study of the incidental music for Symbolist plays’ in Sibelius Studies, ed. Timothy L. Jackson and Veijo Murtomäki, Cambridge University Press (2001).

[1] Ollén, Gunnar 1990, p. 257. ‘Kommentarer: Tillkomst och mottagande Kronbruden-Svanevit’. August Strindbergs Samlade Verk 45. Kronbruden. Svanevit. Stockholms Universitet, pp. 227–271.

[2] Waal, Carla 1990, p. 59. Harriet Bosse. Strindberg’s Muse and Interpreter

[3] Strindberg, August 1976, p. 235. Letter to Harriet Bosse, 18 March 1906. ‘Sibelius får gerna göra Svanehvit.’

[4] The play was given its first Finnish-language performance, together with Sibelius’s orchestral suite, at the Finnish National Theatre in 1930, with Sibelius’s daughter Ruth Snellman in the title role.

[5] August Strindberg’s postcard to Jean Sibelius [without date], postmarked 11 April 1908. Finnish National Archive, Sibelius collection: ‘Mäster Sibelius, Tack för Er vackra musik Ni velat dikta till min vackraste dikt! Snart får jag höra den!’

[6] Strindberg, August 1989, p. 321–322. Letter to Albert Ranft, 27 May 1908. August Strindbergs Brev 16. Maj 1907–juli 1908. Utgivna av Björn Meidal. Strindbergssällskapets skrifter. Albert Bonniers Förlag. Stockholm: ‘Denna matrona, öfver trettio år, får icke förstöra min vackra dikt; och hon får inte misslyckas!’

[7] Strindberg, August 1919, pp. 300–301. Öppna brev till Intima teatern: ‘Prinsar och prinsessor funnos i överflöd; styvmorsmotivet hade jag redan för länge sedan upptäckt som konstant (i 26 svenska sagor); uppväckandet från döden fanns där (och finnes även i Drottning Dagmars historia).’

[8] Movements in the Orchestral Suite: No. 1. The Peacock. Adagio – (Allegro comodo); No. 2. The Harp. Largo; No. 3. The Maidens with Roses. Lento assai; No. 4. Listen, the Robin Sings. Vivace; No. 5. The Prince Alone. Andante sostenuto; No. 6. Swanwhite and the Prince. Allegretto; No. 7. Song of Praise. Largo