Click here to download this article as a pdf file

Exoticism, snake dances, violin playing and ghosts

Eija Kurki discusses Sibelius’s music for the plays ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’ and ‘The Lizard’

The connection between Jean Sibelius and the theatre might at first seem surprising; Sibelius is primarily known as a symphonist. But in fact a significant number of theatre works form an essential part of his production alongside the symphonies, symphonic poems and vocal music. Many well-known works such as Finlandia, the Karelia Suite and Valse triste were originally composed in a theatrical context. Sibelius often reworked his theatre scores into orchestral suites or individual pieces for concert use. In their new forms they have been heard all over the world, but the original theatre scores have remained unpublished and have therefore attracted little attention. Sibelius’s theatre works comprise a one-act opera, music for two sets of historical tableaux, scores of various proportions for eleven plays and a ballet-pantomime. He wrote music for works by international as well as Finnish writers, among the former Hofmannsthal (Everyman) and Shakespeare (Twelfth Night; The Tempest), and among the latter Arvid Järnefelt and Mikael Lybeck.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Sibelius wrote music for Symbolist plays dealing with fairy tales, dreams, death, mysticism and exoticism. These plays included Järnefelt’s Kuolema (Death), Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande, Hjalmar Procopé’s Belshazzar’s Feast, August Strindberg’s Swanwhite and Lybeck’s The Lizard. In this article we shall examine the pieces he wrote for Procopé’s Belshazzar’s Feast and Lybeck’s The Lizard.

Belshazzar’s Feast

Processionals and Snake Dances

The play Belshazzar’s Feast by the Swedish-speaking Finnish writer Hjalmar Procopé (1868–1927) appeared in 1905 and is based on the Old Testament (Daniel 5) story of the feast arranged by King Belshazzar, at which luxuries are enjoyed from holy vessels stolen from the temple at Jerusalem. Daniel interprets the text that appears on the wall in the middle of the feast, ‘Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin’ , as an indication that Belshazzar’s rule is coming to an end. The Book of Daniel tells us that Belshazzar will meet his end on the night after the feast, and this comes to pass in Procopé’s play too. The play’s dialogue and stage directions include significant quotations from the Bible text. The Bible story is only a framework, however, to which more ‘decadent’ elements have been added.

Belshazzar’s Feast at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki, 1914

Photo: Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland archive

The principal characters in Procopé’s play are the Jewish girl Leschanah, who has been chosen to kill Belshazzar, and the dancer Khadra, whose place as Belshazzar’s lover is taken by Leschanah. These two women, who do not appear in the original Bible story, compete for King Belshazzar’s favour. Khadra is reminiscent of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, who is in love with Jokanaan but is rebuffed. Khadra, meanwhile, grows fond of the prophet Ben Oni and wants to kiss him, but he rejects her advances. On the other hand Khadra is the dancer who performs the Dance of Life and Dance of Death; these dances can be compared with Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils.

Sibelius composed the music for Belshazzar’s Feast in the autumn of 1906, while also working on his Third Symphony. It is scored for an orchestra including flute, two clarinets, two horns, percussion (bass drum, cymbal, tambourine, triangle) and strings.

The play begins in Babylon. In the centre of a city square is an idol before which everyone must bow down. The king’s Jewish adviser, Elieser, explains that a young Jewish woman, Leschanah, has been chosen to kill King Belshazzar. The Jewish prophet Ben Oni walks past the idol without bowing down, and is arrested. Also present is Belshazzar’s favourite slave girl, the dancer Khadra, who is in love with the prophet and wants him for herself, even if just for one night. She admires his appearance and wants to kiss him, but Ben Oni refuses to accept her kiss. Leschanah arrives in the square, and Belshazzar arrives as well, with a procession bearing idols. Musicians form part of the procession; Procopé mentions ‘trombones, trumpets, harps, psalters, lutes and all sorts of string instruments ’. (1)

The tempo marking in Sibelius’s score is alla marcia. The gradual increase in the music’s dynamic level depicts the approach of the procession; we hear the beat of the bass drum, cymbal, tambourine and triangle. The strings’ quintuplets create an oriental atmosphere that is intensified by the woodwind solos and the piccolo’s shrill squeals. Sibelius recreates the play’s exotic atmosphere by means of tine colours, scale figures and repetitions. The mood resembles that of the Oriental-themed paintings by the Symbolists’ favourite artist Gustave Moreau, with shining jewels and soaring cupolas. The colourful orchestration of Sibelius’s music glows with the sounds of the percussion, as if in imitation of the radiance of those cupolas and jewels.

In the palace, Leschanah takes the king’s sceptre and demands that her rival Khadra be put to death. Belshazzar cannot countermand this order, but he agrees to allow Khadra to dance for him one last time, and organizes a feast where this will take place. At the feast, Khadra performs the Dance of Life on roses and tiger skins. In Sibelius’s incidental music there is a charming interplay between the flute and clarinet. Like Wilde’s Salome, who asks for Jokanaan’s head in payment for her dance, Khadra demands a price that flouts what is sacred: she wants to drink a toast from the beaker stolen from the temple in Jerusalem. Belshazzar grants Khadra’s request to drink from the holy beaker of Moses.

Having drunk from the beaker, Khadra expresses her gratitude by performing the Dance of Death; Belshazzar is enraptured. She opens a box, from which a glistening, wriggling cobra emerges; she winds the snake around her neck and dances a slow dance. During the dance the snake wakes up and bites her in the chest. Procopé gave the following instructions: ‘Two Hindus… take their flutes, on which they play a monotonous melody… Khadra dances a slow dance in time with the flutes. ’ (2) Sibelius has given the flute melody to the clarinet, which plays a sinuous, chromatic theme. The chromaticism, plus the use of the clarinet’s low register, are Sibelius’s way of writing ‘snake-like’ music. The clarinet melody is accompanied by string pizzicati, remaining for some bars on the note B natural. The steady rhythm of the bass drum adds to the fateful character of these pizzicati.

Sibelius’s theatre score contains a total of eleven numbers, some of which are repeats. The play also includes one vocal number: from the palace, Leschanah hears a Jewish girl, rowing a boat on the river and singing about Jerusalem. Khadra’s Dance of Life is heard three times during the course of the play, and the Dance of Death twice. Their music is heard at the end of the play. Leschanah visits Belshazzar and learns that he no longer loves her. At the same time, from the neighbouring banquet hall, we hear festivities and the sounds of Khadra performing the Dance of Life. Belshazzar remembers how well Khadra danced, and wants to go and see her dead body, but Leschanah prevents him. The sounds of the Dance of Life from the hall are replaced by those of the Dance of Death, and Leschanah kills Belshazzar with a dagger. During the feast Leschanah reveals that the Jews are behind the assassination. The Jewish counsellor Elieser states that Leschanah alone was responsible; he takes the dagger from Belshazzar’s breast and kills Leschanah with it.

And so the three main characters in this drama all meet their end during the play.

The first performance of Belshazzar’s Feast, at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki on 7 November 1906 was an eagerly awaited event and was sold out. The Operakällaren restaurant advertised a special menu inspired by the play’s opening night, featuring ‘Tournedos à la Belsazar’ . Procopé’s play was already to some extent familiar, as it had appeared in print the previous year, and expectations were high for the stage version. The theatre had evidently not spared any expense when it came to creating an Oriental atmosphere by means of costumes, stage sets and decor. The stage production was praised: ‘for it is rare in Helsinki to see something as splendid in terms of accoutrements as Belshazzar’s banquet hall with its imposing architecture, and the three groups of reclining women, all with naked arms and decked out with roses.’ (3)

The poet and journalist Eino Leino described the play as ‘a stylish series of tableaux’, and the staging in particular was singled out for praise: ‘The theatre director deserves full credit for this very unusual production, as does Mr Knudsen for his exceptional designs. In this respect the feast scene itself was the highlight. ’ (4) In all Belshazzar’s Feast was performed 21 times in 1906–07, and this exotic spectacle was the season’s most popular production at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki. It was staged there again in 1914.

At the première of Belshazzar’s Feast, Sibelius conducted an orchestra backstage. His music attracted attention even before the event, and received positive reviews even though the comments tended to be short, as they appeared in the context of articles about the stage play.

Sibelius revised the stage score for Belshazzar’s Feast to produce a concert suite that was published in 1907. The suite has four movements: Oriental Procession, Nocturne, Solitude (an instrumental version of the Jewish Girl’s Song in the theatre version)and Khadra’s Dance (combining the original Dance of Life and Dance of Death). Three of the original musical numbers were omitted from the suite.

Belshazzar’s Feast at Helsingin Kansanteatteri, 1950.

King Belshazzar is surrounded by his courtiers

Photo: Finnish Theatre Museum archive

Sibelius’s original theatre score manuscripts for Belshazzar’s Feast found at Ainola

The first Finnish-language performance of Belshazzar’s Feast (translated by Lyyli Järviluoma) with Sibelius’s music took place as late as 1950, and was given by Helsingin Kansanteatteri (predecessor of the Helsinki City Theatre) at the Old Student House in Helsinki. The theatre manager and director at the time was Glory Leppänen (1901–79) who, as the daughter of the soprano Aino Ackté, was also interested in music. Leppänen had studied direction at the famous Max Reinhardt Seminar in Vienna in 1933–34. She had previously directed Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Everyman with Sibelius’s music at the Finnish National Theatre in Helsinki in 1935, and at the Tampere Theatre in 1947.

After listening to the orchestral suite from Belshazzar’s Feast, Glory Leppänen started to wonder about the play for which Sibelius had composed these ‘brightly sparkling musical images ’ : what was it actually like? For the performances she directed, she was keen to use Sibelius’s theatre score rather than the concert suite. Sibelius was asked about the original score, but he thought it had been destroyed in the bombing of Leipzig while in the possession of his German publisher. Nevertheless, Jussi Jalas managed to locate the manuscript at Ainola. In the resulting production, the Helsinki Theatre Orchestra was conducted by Yngve Ingman. Ten performances were given, and the production was one of the greatest successes of the theatre’s season.

The original theatre music for Belshazzar’s Feast was recorded for the first time in 1995, but the score and parts remain unpublished.

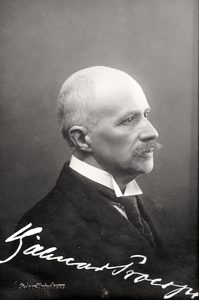

Hjalmar Procopé, 1910s

Photo: Salon Strindberg (CC BY 4.0)

The Lizard

Violin Playing and Ghosts

The Swedish-speaking Finnish playwright Mikael Lybeck (1864–1925) was in Sibelius’s circle of friends at the beginning of the twentieth century. Ödlan (The Lizard) was his first drama, completed in 1908. The events of the play take place at the start of the twentieth century at the Eyringe family manor, a week after the death of Count Ottokar, head of the household. His successor, the 23-year-old Alban, is engaged to the innocent 19-year-old Elisiv, who had been the previous count’s nurse. Also present at the manor is Alban’s 31-year-old cousin Adla, who wants Alban and the manor for herself. In Act I, Alban describes to Elisiv how, when he was eleven, Adla had once dressed up as a lizard. On her head she wore a little golden crown with sixteen stars, like in the Eyringe family’s coat of arms, which features a lizard. In Alban’s opinion the lizard suited her well, not just because of the similarity of names (Adla/Ödlan) but also because of the way they behave:

‘The lizard is an unusually clever creature; it gathers experience and changes its behaviour accordingly. Its neural life is superior to others ’ . There are also venomous lizards. And have you noticed how quiet she gets in winter? Like in a daze (…) She’s totally different in winter. But when spring comes, and early summer… Do you think I’m exaggerating? And yet… yes, it’s absurd!… a little detail: she can’t stand it if someone smokes in her presence. And nicotine is a deadly poison for lizards. Instantaneous, they say. It’s no coincidence that she is so attached to Eyringe… so passionately. ’ (5)

Alban is caught between two women, the demonic, sensual Adla and the pure, sensitive Elisiv. In the play’s dualistic portrayal of women, good and evil are clear opposites. According to the Finnish literary scholar Erik Kihlman, the ‘dark’ and ‘light’ women form a pair, like a ‘demon’ and ‘valkyrie’. (6) The lizard-like Adla is a femme fatale – a fateful female figure who, in turn-of-the-century literature, was deadly but in the end usually died herself, comparable with Frank Wedekind’s Lulu or Wilde’s Salome. In Lybeck’s play, a small lizard representing Adla frightens Elisiv so much that she falls down the stairs. Elisiv subsequently dies, and Adla thinks she has won Alban, but at the end of the play Alban avenges Elisiv’s fate by pushing Adla, who is dressed in a green lizard costume, off the balcony. With Adla’s death, the family’s lizard coat of arms shatters.

In paintings from the time, too, we find figures similar to Adla and Elisiv. As the French art historian Philippe Jullian has pointed out, Salome-like characters appear in paintings by artists such as Gustave Moreau; his ‘beauties walk freely over the corpses of their admirers and drag their silken draperies through pools of blood. To these Salomés… are opposed the Ophelias, the pale creatures destined to a watery grave with hair undulating like seaweed’ (7), and in literature they die at the hands of fateful women or evil men.

In the autumn of 1909 Sibelius composed two musical numbers for The Lizard, scoring them for small string ensemble. In Lybeck’s play music is of central importance, as is evident from the stage directions. The playwright gave precise instructions about where and what sort of music should be heard. Sibelius followed these guidelines; in his score he has marked lines and stage directions from the play. Consequently it is possible to follow the correlation between the play text and the music in detail.

The first musical number is for the end of Act II Scene 1, where Alban takes Elisiv to see the family’s funeral chapel. He has brought a violin with him: by playing it he wants to make contact with his deceased relatives. In the musical number Alban plays the violin, accompanied by the small string group. The music starts after Alban has spoken the words ‘Now I’ll let my soul rise up!’ (8) It begins with a two-bar introduction, the solo violin colouring the string texture. In Lybeck’s play, Alban’s playing makes Elisiv forget her fear. Elisiv feels as if she is in a big, flowering meadow, with the sun shining, and small children dancing a round hand-in-hand.

The mood changes immediately when Elisiv hears a child crying in the distance. At this point in Sibelius’s score, Alban’s playing stops. Elisiv’s vision of a sunlit meadow changes to something darker; she sees an abandoned graveyard. Above a background of syncopated violins we hear a viola and cello theme, dominated by rising and falling chromaticism. The sound of the music causes the graves to open; the chromaticism of the small string ensemble wakes the dead.

It becomes darker still; ghosts flit around the main door of the chapel, and Alban establishes contact with the departed. Alban’s solo violin plays espressivo above a tremolo from the other strings. The figure of the old Count Ottokar soars above the clearing. Alban’s solo violin melody rises higher and higher. Terrified by what she is seeing, Elisiv calls out to Alban; the solo violin stops playing and, immediately, darkness falls.

The second musical number is for Act II Scene 3, where Elisiv, after her fall, has delusions as she hovers between life and death. In her feverish visions she sees the dead waiting for her at the funeral chapel, and hears their conversation. The music is heard throughout this long scene. Lybeck’s instructions specified that the ghosts should hover over a megalith, and that a supernatural light should fall over the stage that would give everyone the impression of having been turned to stone. The ghosts remain at the megalith: ‘No gestures – sometimes a slight swaying of the upper body. ’ (9) The chromaticism in Sibelius’s score can be seen as an illustration of the ghosts’ material state, whilst the violins’ triplet figures portray their hovering.

Accented notes depict how Elisiv approaches the ghosts. Later this motif is transformed into Elisiv’s death theme. In her delirious state she hears Alban playing his violin, the same melody that he played at the funeral chapel. Elisiv is ready for her life to end, and asks that Alban’s playing might carry her soul across the divide. The violin theme guides Elisiv towards death; at this point Sibelius marks his score dolcissimo.

Overall the musical number is characterized by chromaticism and syncopation. Its repetitiveness creates a mystical atmosphere – or, as the Finnish musicologist John Rosas called it, ‘life’s meditation’. (10)

The scene at the end of The Lizard where Alban throws Adla from the balcony

The Lizard’s Fate

The first night of Lybeck’s play at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki on 6 April 1910 had been eagerly anticipated for a number of reasons. For a start it was the world première of a new play by a Finnish author. The theatrical production itself was eagerly awaited because the text of Lybeck’s play was already familiar, having been published two years previously. The inclusion of music by Sibelius was a further attraction.

Eino Leino reviewed the production: he was not impressed, finding fault both with the text and with the direction. Leino longed for a more lavish staging and in his view Valborg Hansson, who played the Lizard, lacked a deeper, mystical undercurrent. On the other hand Julius Hirn, who also reviewed the play, liked Hansson’s performance: ‘power, passion, cool calculation, lizard-like agility of movement and seductive beauty of form’. (11) Sibelius conducted the music at the première and, according to the reviews, both Lybeck and Sibelius ‘came on stage time after time to accept the audience’s accolades.’ (12)

In earlier reviews of theatre performances that featured scores by Sibelius, Leino had not remarked on the music at all. It is therefore interesting that on this occasion he does mention it: ‘With the aid of Sibelius’s music, once in a while we get a hint of the mystical, semi-twilight atmosphere that the author intended, and we regret that its beauties are not clothed in a more dramatic form.’ (13) This ‘mystical, semi-twilight atmosphere’ can be regarded as characteristic of the Symbolist artistic movement.

Sibelius’s contribution was mentioned in reviews by various music critics too. On the day of the première Karl Fredrik Wasenius (with the pseudonym Bis) wrote a long article about Sibelius’s new theatre score. Probably Wasenius had seen the score or had attended rehearsals, as he goes into detail about the music’s relationship to the events on stage. Wasenius drew attention to the music’s impact: ‘Nowhere does the music stand still; rather, it undergoes constant psychological transformations to an extent that gives it a unique status within the melodrama genre.’ (14) He also found its chamber-music-like qualities remarkable: ‘And this is achieved by means of a small string orchestra, without the mass impact of a modern orchestra! This circumstance places Sibelius’s mastery in an even more advantageous light. ’ (15)

The Operakällaren restaurant advertised a special ‘Lizard menu’ in honour of the first night. It included ‘Marquise Sibelius ’ , but Mikael Lybeck did not have a dish named after him. This tells us something about Sibelius’s position within Finnish cultural life in 1910. Despite a few critical asides, the première was well received by the press, but it did not find favour with the public, as Ester-Margaret von Frenckell has pointed out: ‘not even the music drew audiences to this subtle play ’. (16) It was performed just six times in 1910, and has not returned to the Finnish stage since then.

Just after finishing the work, Sibelius described his score for The Lizard to his friend Axel Carpelan: ‘The score for Lybeck’s Lizard became one of the most full of feeling that I have written. ’ (17) After the first night he noted in his diary: ‘The Lizard was a success. The music, I mean. ’ (18)

Years later he told his son-in-law, the conductor Jussi Jalas, that ‘there are passages in it where the ghosts go around on stage for a long time dressed in white sheets… How undramatic ! ’ (19)

Sibelius’s fellow-student and friend, the writer Adolf Paul, who had moved to Berlin where he championed Sibelius’s music, made a German translation of the play (Die Eidechse), and this was published in 1909. From the correspondence between Sibelius and Paul it becomes clear that Paul tried to organize performances in Germany in which Sibelius’s music would be used. (20) A translation into Finnish was also considered, and Lybeck thought of asking Eino Leino to do this – but nothing came of it.

In 2014, in the context of the 150th anniversary of Lybeck’s birth, the two scenes from Act II of the play that use Sibelius’s music were performed at Helsinki University Hall at the annual celebrations of Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland (the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland).

Mikael Lybeck

Photo: Atelier Rembrandt (Public Domain)

Sibelius’s Lizard among Lybeck’s possessions

According to the contract between Sibelius and Lybeck from 1909, the score and parts passed into Lybeck’s ownership in exchange for a fee. After his death in 1925, the material formed part of his estate, and it was here that the Sibelius researcher Harold Johnson found the original manuscript in the late 1950s. In 1960 Lybeck’s heirs donated Sibelius’s manuscript to the Sibelius Museum in Turku.

In 1988 the orchestra in Kauniainen, Lybeck’s home town, performed the music at the initiative of the playwright’s heirs. On this occasion the composer Pehr Henrik Nordgren (1944–2008) made some changes to the score. (21)

The 1909 contract also states that Sibelius would have to pay part of the fee back to Lybeck if he wanted to revise the work for concert use. Sibelius offered it to his German publisher Breitkopf & Härtel, who sought the views of a specialist in whose opinion the music could not be understood away from its original dramatic context. The score remained unpublished for decades. In the German translation of the play, however, it is stated that the material is available from Breitkopf & Härtel.

In 1996 two recordings of the music for The Lizard appeared, both using the original manuscript score and parts. The following year, the music was published by Fazer (now Fennica Gehrman). Unfortunately no photographs of the 1910 production have survived. It would be fascinating to see a stage production of the play including the music, making full use of the possibilities of modern technology.

© Eija Kurki 2018

Eija Kurki D. Phil. published her dissertation Satua, kuolemaa ja eksotiikkaa. Jean Sibeliuksen vuosisadan alun näyttämömusiikkiteokset (Fairy-tale, Death and Exoticism. Jean Sibelius’s Theatre Music from the Beginning of the 20th Century) in 1997. She has written numerous articles in various specialist publications both in Finland and internationally (e.g. Sibelius Studies, Cambridge University Press 2001).

This article is a revised version of a text that appeared in the book Dekadenssi vuosisadanvaihteen taiteessa ja kirjallisuudessa, ed. Pirjo Lyytikäinen (SKS, 1998). English version published in Sibelius One Magazine, January 2019. Translation: Sibelius One.

(1) ‘Basuner, trumpeter, harpor, gigor, psaltare, lutor och allehanda strängaspel ljuda.’

(2) ‘Två hinduer… framtaga… sina flöjter, på hvilka de blåsa en entonig melodi… Khadra… dansar en långsam dans i takt till flöjtspelet ’ .

(3) ‘ty det är sällan man i Helsingfors fått skåda något så vackert i utstyrselväg som Belsazars gästabudssal med dess impossanta arkitektur och de tre färgrika grupperna af halfliggande kvinnor, alla med nakna armar och prydda med rosor. ’ Thf. (pen name of unidentified writer), Nya Pressen, 8 November 1906

(4) Eino Leino in Helsingin Sanomat, 9 November 1906: ‘tyylikäs kuvaelmasarja… Teatterinjohtaja ansaitsee täyden tunnustuksen todellakin harvinaisista näyttämöjärjestelyistään, samoin kuin hra Knudsen erinomaisista dekorationeistaan. Pitokohtaus oli tässä suhteessa huippu. ’

(5) ‘Ödlan är ett ovanligt klokt djur, den samlar erfarenhet och ändrar sitt uppförande därefter. Har ett högre nervliv än andra. Det finns också giftliga ödlor. Och har du märkt hur stilla hon är om vintern? Liksom i dvala. […] Hon är en helt annan om vintern. Men när våren kommer och försommarn… Du tror att jag överdriver? Dessutom… ja det är löjligt… en småsak: hon tål ju inte att någon röker i hennes närvaro. Och nikotin är för ödlorna ett gift som dödar. Ögonblickligen – säger man. Att hon är så fäst vid Eyringen så passionerat… det är ingen tillfällighet. ’

(6) Erik Kihlman, Mikael Lybeck: liv och diktning. Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland, Helsinki 1932, pp. 392–393

(7) Philippe Jullian: ‘The Esthetics of Symbolism in French and Belgian Art’ (translated from the French by Édouard Roditi) in: The Symbolist Movement in the Literature of European Languages, ed. Anna Balakian, Budapest 1982, p. 533.

(8) ‘Nu låter jag själen stiga!’

(9) ‘Inga gester – ibland en sakta vaggning med överkroppen. ’

(10) John Rosas, Sibelius’ musik till skådespelet Ödlan. Suomen Musiikin vuosikirja 1960–61, Helsinki, pp. 49–56

(11) Julius Hirn in Nya Pressen, 7 April 1910: ‘kraften, glöden, den kalla beräkningen, den ödlelike smidigheten i rörelserna och den förföriska skönheten i det yttre’.

(12) ibid.: ‘Efter föreställningens slut bröt en bifallsstorm lös, som icke lade sig innan de uppträdende samt författaren och kompositören gång på gång franträdt för att mottaga publikens hyllning. ’ See also Kurki, Satua, kuolemaa ja eksotiikkaa. Jean Sibeliuksen vuosisadan alun näyttämömusiikkiteokset, 1997, p. 205

(13) Eino Leino in Helsingin Sanomat, 10 April 1910: ‘Sibeliuksen musiikin avulla, silloin tällöin saamme aavistuksen tekijän tarkoittamasta mystillisestä puolihämäräisestä mielialasta ja valitamme, että sen kauneudet eivät ole draamallisimpiin muotoihin pukeutuneet. ’

(14) Karl Fredrik Wasenius in Hufvudstadsbladet, 6 April 1910: ‘Musiken står ingenstädes stilla, utan undergår städse psykologiska omgestaltningar i en vidd, som förlånar den en enastående rangplats inom melodramets område. ’

(15) ibid: ‘Och dette med medlen af en liten stråkorkester, utan masseffekten af en nutida orkester! Denna omständighet ställer Sibelius’ mästerskap i än idealare belysning. ’

(16) Ester-Margaret von Frenckell, ABC för teaterpubliken, Borgå 1971, p. 188: ‘Inte ens musiken drog folk till denna subtila pjäs. ’

(17) Letter dated 19 November 1909: ‘Musiken till Ödlan af Lybeck, blef något af det känsligaste jag skrifvit. ’

(18) Diary, 8 April 1910: ‘Ödlan haft succés. D.v.s. musiken. ’

(19) Jalas 1984: ‘siinä on kohtia, joissa haamut pitkän aikan kulkevat näyttämöllä valkoisiin lakanoihin puettuina, ja [Sibelius] lisäsi: Kuinka epädramaattista ! ’

(20) See Fabian Dahlström (ed.): Din tillgifne ovän. Korrespondensen mellan Jean Sibelius och Adolf Paul 1889–1943. Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland, Helsinki 2016, pp. 266–270

(21) Pehr Henrik Nordgren: Sibelius, Lybeck ja Sisilisko. Kauniainen Orchestra concert programme, 19 May 1988