Click here to download this article as a pdf file

Eija Kurki

In the late 1940s Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet premièred two choreographies which used Jean Sibelius’s music: Khadra and Sea Change. Khadra was choreographed in 1946 by Celia Franca (1921–2007) to the Belshazzar’s Feast suite. Sea Change was a choreography by John Cranko (1927–73), which Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet premièred in Dublin in 1949 and which was subsequently performed in London. The ballet was based on Sibelius’s tone poem En saga. [1]

Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet was a new company of young dancers and choreographers that performed from 1946 onwards at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in Islington, after Sadler’s Wells Ballet – which had previously performed at the theatre – had moved to the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, where it later assumed the name Royal Ballet.

Both choreographers, Franca and Cranko, were young dancers who danced or had previously danced either with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet (Celia Franca) or with both of these companies (John Cranko). Khadra was the 24-year old Celia Franca’s first ballet choreography for the company – indeed, the first major choreography that she ever undertook. She subsequently made her career as founder and director of the National Ballet of Canada. John Cranko, at the age of 21, had made some choreographies earlier, but Sea Change was his first major project for the company, to be followed by several others that made him famous. Later, as a director of the Stuttgart Ballet, Cranko developed that company and made choreographies for it that were also performed by other ballet companies worldwide.

Both these dancers, in fact, started their careers as choreographers with Sibelius’s music, specifically with short one-act works, around 15–20 minutes in duration. Celia Franca’s Khadra, which used the Belshazzar’s Feast suite, Op. 51 (1907, arranged for concert performance from the incidental music of 1906), played for around 15 minutes, and had a Persian theme. John Cranko’s Sea Change, a ballet related to the sea as its name indicates, is based on Sibelius’s tone poem En saga, Op. 9, composed in 1892 and revised in 1902, and takes around 18–20 minutes.

This article will also discuss the people who made designs and costumes for these choreographies. Honor Frost (1917–2010) designed the set and costumes for Khadra and wrote a short book about the production, How a Ballet is Made (1948), which includes many of her drawings and also photographs of the production. Later she became a renowned sea archaeologist. The set and costumes for Cranko’s Sea Change were by John Piper (1903–92), a famous English painter.

SADLER’S WELLS THEATRE BALLET

Sadler’s Wells Ballet, which had performed at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre, moved to the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and was later named the Royal Ballet. In its former headquarters, Sadler’s Wells Theatre, a new ballet company was established – Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet, to appear in opera ballets in that theatre and to give occasional performances of its own. Ninette de Valois (1898–2001) was director of both these ballet companies. The new company’s first performance took place on 8 April 1946 at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre.

The company’s dancers were young, some still students at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School (now the Royal Ballet School). The company consisted essentially of soloists or potential soloists, and a corps de ballet of the dimensions needed at Covent Garden was not required for its performances.

The Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet was envisaged from the beginning as a stepping stone to Covent Garden; a stage where dancers and choreographers could gain practical experience before moving on to more august precincts of the Royal Opera House. The repertoire consisted mostly of contemporary ballets by young artists – young painters and musicians as well as choreographers. Young dancers were encouraged to make choreographies and during the first nine years of its existence fifteen different choreographers produced ballets for the company.

An American tour in 1951–52 completed the process of turning the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet into a completely professional company with a distinct personality and assurance.[2] Today this company is called Birmingham Royal Ballet, after its relocation there in 1990.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH

It is surprising that neither of these ballets, Khadra and Sea Change, is mentioned in the literature related to Sibelius and also, at first glance, it seems that very little is known or has been written about these two choreographies. John Cranko’s Wikipedia page mentions Sea Change and its designer John Piper, but not Sibelius; and the article about Celia Franca does not mention her ballet Khadra at all.[3]

They have not, however, remained unknown for ballet researchers.

In Horst Koegler’s Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet from 1987, both these ballets are listed as titles of choreographies made to Sibelius’s music (head word: Sibelius).[4] The introduction to Celia Franca mentions that Khadra is based on Belshazzar’s Feast.[5] There is even the head word Khadra describing the plot of the ballet which ‘enfolds [sic] as a series of Persian miniatures around K. [Khadra], a young girl, who is full of wondering astonishment at what life holds for her.’[6]

In the introduction to John Cranko, however, there is no mention of Sea Change at all.[7] It is, however, mentioned in Otto Friedrich Regner’s Das Ballettbuch from 1954, which tells that Cranko made use of Sibelius’s En saga and summarizes the plot: ‘in a fishing village the wives are waiting for the return of their husbands from fishing – one of them does not return.’[8]

In Martha Bremser’s International Dictionary of Ballet both these ballets are listed – both in connection to Cranko and Franca and also as using Sibelius’s music – but there is no mention of which of his compositions were used.[9]

In The Sadler’s Wells Ballet. A History and Appreciation (1955), written by Mary Clarke, there are only a few lines about Khadra and Sea Change and no mention in either case that Sibelius’s music was used with the choreographies.[10] An appendix to the book provides the background and the history of the early years of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet in a condensed form.

J.P. Wearing’s London Stage Calendars – which are extremely important as a source of research as they list the performances and performers according to years – state that both the choreographies had music by Sibelius, but not the names of the pieces used.[11]

Both choreographers have been the subject of biographies, however, which mention these works. Carol Bishop-Gwyn’s The Pursuit of Perfection. A Life of Celia Franca (2011) discusses Khadra, and John Percival in Theatre in My Blood. A Biography of John Cranko (1983) writes about Sea Change.[12] Sibelius’s name is mentioned (on one page) in the text, but unfortunately both books have omitted his name from the index.[13]

Regarding Khadra, there is Honor Frost’s book How a Ballet is Made (1948). It is a short book of 27 pages and it has precious information about the production. The book focuses solely on Khadra and explains how the ballet was conceived and built up. She describes the work of the choreographer Celia Franca and the décor and costumes designed by herself. It has an illustration of the stage backdrop with its vivid pinks, reds, golds, and greens invoking a Persian art style, along with coloured costume illustrations. It also includes photographs of the ballet taken by Roger Wood and Churton Fairman.[14]

In addition to Honor Frost’s book there are photographs in the Royal Opera House archive, both black and white photographs and in colour. The photographs are in Roger Wood Photographic Collection and Frank Sharman Photographic Collection; both can been seen online. In the credits for all these photographs naming the choreographer, designer, dancers etc., however, there is no mention that Sibelius’s music was used (according to the situation on 5 March 2021).

In 2019 an anthology of Honor Frost’s life and work was published, In the footsteps of Honor Frost. The life and legacy of a pioneer in maritime archaeology (2019, ed. Lucy Blue). In that anthology there is an article by Sophie Basch that deals with Khadra: Honor Frost, True to Herself. From art and ballet to underwater archaeology.[15]

Besides John Cranko’s Sea Change, there are also other works with that same name: Sea-Change, choreographed by Alvin Ailey to music by Benjamin Britten at the American Ballet Theatre (1972) and an aquatic performance Sea Change by the Wet Hot Beauties (2017) in Parnell Baths, Auckland as part of Auckland Fringe in New Zealand.[16]

In the 1930s and 1940s Sibelius’s popularity was at its peak in the United Kingdom. Sir Thomas Beecham regularly conducted Sibelius with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Choreographies to Sibelius’s music were performed at the Ballet Rambert in 1930s and 1940s in London: Frederick Ashton’s (1904–88) The Lady of Shalott (1931) and Walter Gore’s (1910–79) Confessional (1941) and Antonia (1949).[17] In addition Antony Tudor (1908–87), Celia Franca’s ballet teacher, had planned a ballet already in 1936 with Sibelius music, based on stories from the Finnish national epic, Kalevala.[18]

In 1946 there were two Sibelius’s ballets on stage in London at the same time: Khadra at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre and a further performance of Walter Gore’s Confessional, this time at the King’s Theatre with 3,100 seats (demolished in 1963). Gore’s new work with Sibelius’s music, Antonia, was performed in 1949 at the King’s Theatre, at the same time as Cranko’s Sea Change at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre. Later in 1950s Gore made a third choreography with Sibelius’s music, Ginevra (1956) in the Netherlands for Het Nederlands Ballet, predecessor of the National Ballet.[19]

All these Sibelius choreographies by Frederick Ashton and Walter Gore will be discussed in a separate article.[20]

KHADRA

CELIA FRANCA AND HONOR FROST

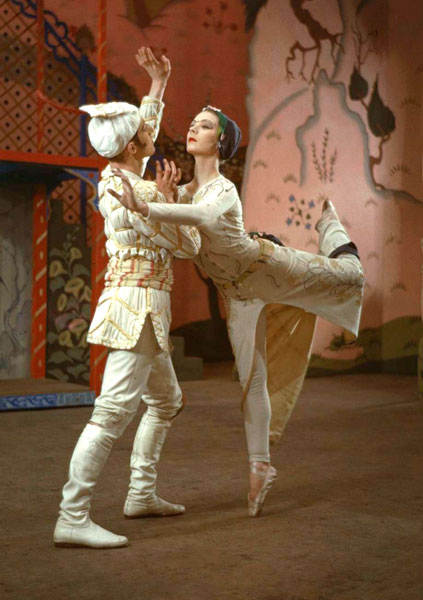

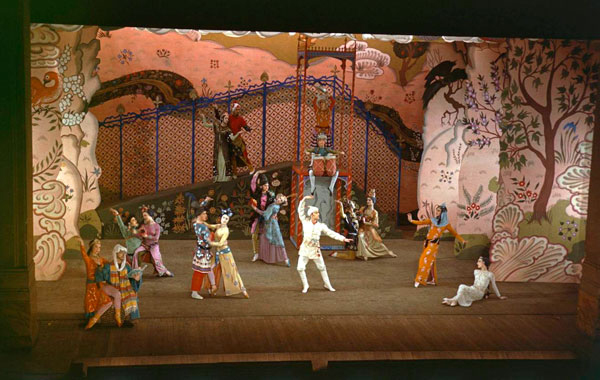

The première of Khadra was on 27 May 1946 at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre. The ballet was influenced by Persian miniatures and the story, invented by the choreographer Celia Franca, is as follows: ‘From her own independent world, Khadra, the young girl, watches the life around her. She sees the Lovers, whose solitude is disturbed by the assembled characters. She joins them all and at nightfall sees the pictures of their mingling shadows.’[21]

Celia Franca (née Franks) was born in 1921, daughter of a tailor from a family of Polish Jewish immigrants in London’s East End. She began to study dance at the age of four and was a scholarship student at the Guildhall School of Music and the Royal Academy of Dance, taking piano and ballet lessons. In 1936, as a fourteen-year-old, she auditioned for a dance part in a new West End musical starring Walter Gore and Maude Lloyd, and became one of the chorus girls. She dropped out of school and set out to educate herself in the world of professional dance. Franca joined the Marie Rambert School where her teacher was Antony Tudor, and in the early 1937 Marie Rambert (1888–1982) invited her to join the company’s corps de ballet.

Celia Franca, 1946

Unknown photographer / Library and Archives Canada, e006581395.

Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence

The years spent with Ballet Rambert were ‘the bedrock of her professional training’.[22] She married Leo Kersley, her dance partner at the Rambert Ballet, in 1941; they separated the following year and divorced officially in 1948.[23]

Franca joined the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1941 as a dramatic ballerina and danced with the company on tours during World War II.[24] She had choreographed Midas (1939) for ‘Les Ballets Trois Arts’, the company in which she danced at the time, and three years later a small piece, Cancion (1942, with which Ninette de Valois ‘had been impressed’) for the Ballet Guild.[25] She thus had very limited experience of making choreography but the director Ninette de Valois gave her this opportunity as a compensation for giving her only minor dancing roles after the war.[26]

The designer Honor Frost was born in 1917 and grew up in Cyprus. She was the only child of a banker and, orphaned while still a child, she became the ward of discerning art collector and wealthy solicitor Wilfrid Evill, who saw to it that she had a good education at the École Vinet in Lausanne.

In the early 1930s Frost moved to England and attended Eastbourne High School and Eastbourne School of Arts and Crafts from 1932 until 1937. After her art studies Frost produced cartoons published in Clare Market and engraved etchings and woodcuts for Linden Broadsheets in the years 1938–40. During the war she was in the National Fire Service (NFS) and later also worked in the Arab section of the BBC.[27]

Before Khadra, Frost was already involved with ballet through the Oxford University Ballet Club. She had designed the decor for Porphyria’s Lover (1941) by Walter Gore performed at the Club and a cover page of the dance magazine Arabesque in the early 1940s.[28] [29]

Sophie Basch writes about Celia Franca and Honor Frost: ‘No one could imagine the association of two more contrasting backgrounds.’[30]

BACKGROUND OF THE BALLET KHADRA

Bishop-Gwyn writes: ‘Celia already had the germ of an idea using Sibelius’s Night Music. She told Cyril [Frankel], “Well, to cut a long story short with Gerald’s [Frankel] help I got the scenario fixed up. Then when Gerald left I spent a couple of days locked up at home and got the choreography worked out… Now I shall write to de Valois and suggest it. She will refuse and that will be that.’[31]

In the beginning there were two young men involved with the planning of Khadra, Cyril and Gerald Frankel, who were cousins. The latter had introduced the former to the world of ballet. Cyril Frankel (1921–2017) was a law student at Oxford University, had founded the Oxford University Ballet Club and had began publishing the dance magazine Arabesque for which Frost had designed a cover in 1943.[32]

While Gerald was helping Franca with the scenario, his cousin Cyril had introduced her to the designer Honor Frost.[33] Frost writes about her first meeting with Franca when planning Khadra: ‘During that first evening she told me the scenario, she played the records of Belshazzar’s Feast on a deplorable portable gramophone, danced all the principals’ roles, breathlessly explained the positions of the imaginary Corps de Ballet. I questioned her, we went over certain passages again, and, thanks to her efforts, I left with the whole shape of the ballet clearly in my mind.’[34]

Though they were listening to records, Celia Franca was also able to read music as she had taken piano lessons for several years. Frederick Ashton used her knowledge of music while preparing his new ballet The Quest (1943) with William Walton’s (1902–83) music.[35]

The ballet Khadra had a Persian theme which fascinated both Honor Frost and Celia Franca. Honor Frost writes in How to Make a Ballet:

‘Celia Franca, the choreographer, had also been fascinated by Persian paintings and she saw these paintings in terms of balletic possibilites. The primitive convention, for instance, through which perspective is shewn by the figures in the foreground being placed at the bottom and those behind them (though the same size) a little higher up on the page ; the application of this perspective to the drawing of the figures themselves, the shoulders usually square to the front, the head turned stiffly in profile; their stylisation and formality – all this made her think of a new type of conventional movement which could be applied to dancing. When she heard the music of Sibelius’s Belshazzar’s Feast, it occurred to her to couple it with the movements inspired by the Persian prints, and it was then that she realised that she could make her imaginary world come to life.’[36]

Frost considered her own contribution: ‘How can I bring to life on the stage the world of the Persian miniatures?’ My qualifications for this task were familiarity with Persian art and with the life of the East, where I was born and brought up.’[37]

Franca’s biographer Bishop-Gwyn writes: ‘Their encounter quickly developed into a true partnership with Frost designing the elaborate costumes and set designs. In order not to waste time, Celia moved to Frost’s flat near Baker Street for close three months, working from early morning until past midnight. Along with rehearsing the dancers, Celia sewed costumes with Honor in the evenings.’[38]

There were articles in the newspapers about preparations for the performance of Khadra and these ‘two women – Celia dark-haired and glamorous, Honor blond and usually dressed in trousers – attracted a good deal of publicity’.[39]

According to Bishop-Gwyn, the plot of Khadra was transparently autobiographical. She writes: ‘Celia’s estranged husband Leo said, “Khadra, to whom it all happened, was really the Choreographer when Young, for as a child, Franca used to sit on the kerbstone, apart in her own world, watching the other children playing in London’s somewhat Oriental east end.”’[40]

SIBELIUS’S MUSIC: BELSHAZZAR’S FEAST

The music in Khadra was Sibelius’s Belshazzar’s Feast suite, and in addition there was his Romance in C major, Op. 42, as an overture.[41]

Honor Frost explains: ‘The story, or rather theme, of Khadra was directly inspired by the moods in the music. Even the name came from the movement called Khadra’s Dance. A choreographer thinks in terms of moods, and to fit these into a literary-cum-theatrical theme sometimes necessitates the rearrangement of the music. For Khadra two fast movements and two slow movements were made to alternate, so as to give contrast to the work.’[42]

Sibelius’s Belshazzar’s Feast suite has the following movements: 1. Oriental Procession, 2. Solitude, 3. Nocturne and 4. Khadra’s Dance.

The order of the orchestral suite was rearranged to fit in with the ballet’s plot, starting with the last number in the suite. The first scene, called Khadra’s Dance, was followed by The Lovers’ Dance, which is No. 2, Solitude, in the suite. The scene called Oriental Procession came next, originally the first number in the suite, and finally there was the scene called Night Music which used used No. 3, Nocturne, from the suite.[43]

In 1907 Sibelius had arranged a four-movement orchestral suite from his incidental music to Belshazzar’s Feast, originally composed the previous year for Hjalmar Procopé’s oriental play (1905) with the same name based on the Old Testament (Daniel 5) story of the feast arranged by King Belshazzar, at which luxuries are enjoyed from holy vessels stolen from the temple at Jerusalem. Daniel interprets the text that appears on the wall in the middle of the feast, ‘Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin’, as an indication that Belshazzar’s rule is coming to an end.[44] As Honor Frost writes, they knew that Belshazzar’s Feast was incidental music for a play and ‘it could be played without any re-scoring by the orchestra at Sadler’s Wells Theatre.’[45]

Celia Franca’s choreography shifts the oriental Old Testament atmosphere of Hjalmar Procopé’s play to another oriental location: Persia. Not only the sets and costumes but also the choreography was influenced by Persian paintings. Frost explains Franca’s choreographic principles, where the shoulders were turned at right angles to the hips, heads in profile, and arms held in positions which showed up well in silhouette. The other feature was the length of the bodies and ‘Celia Franca broke up the other lines – i.e., the arms and legs. Dancer’s wrists, knees and elbows were always bent. The fingers are usually kept closed, this is also typical of Persian paitings, where the artist found the simple shape of the closed hand easiest to draw.’[46]

After describing the Persian influences in detail, Frost continues: ‘Belshazzar’s Feast has an Oriental flavour, but it still keeps the characteristics of European romantic music. In parts, it has a “roundness” which dictates rounded, sensuous movements in the dances – movements more evocative of classical ballet than of Persian painting.’[47]

The oriental features in Sibelius’s music for Belshazzar’s Feast were based on the influences of the play by Hjalmar Procopé. Sibelius also composed music for another play with an oriental theme, Adolf Paul’s The Language of the Birds, for which he wrote a Wedding March (1911).[48]

ORIENTALISM

Orientalism has proved popular in all fields of art. In his book Orientalism. History, theory and the arts (1995) John M. MacKenzie, examining the visual arts, architecture, design, music and theatre, writes that the western arts received genuine inspiration from the East. Orientalism was especially present in the Ballets Russes at the beginning of the twentieth century, for example in Sheherazade (1910) by Rimsky-Korsakov with designs by Léon Bakst (1886–1924). In the chapter dealing with the theatre MacKenzie stresses the Ballets Russes and its orientalism in stage design and also choreography:

‘Costumes and backcloths were designed with bold blocks of colour, intricate traceries of patterning, stripes, chevrons or interlocking geometrical forms. Clothed in such costumes, and set against flying drapes and exotic backdrops, the dancers created new moods: religious reverie, majestic display, unbridled sexuality or fabulous myth, conveyed by extremes of languor and muscular frenzy, slow unfolding patterns, twisting arabesques, sensual motions, themselves emblematic of the non-linear, curved and mobile character of eastern design. The key point, however, is that these Orientalist creations served to influence design, movement and procustions in the musical theatre generally. Those that ceased to have any connection at all to supposedly eastern themes still bore the mark of this revolution.’[49]

While dealing with music and the orientalist works by Mozart, Bizet and also British composers as Granville Bantock and Gustav Holst, however, he does not mention Sibelius’s Belshazzar’s Feast, nor is Celia Franca’s Khadra discussed in his chapter dealing with theatre and dance.[50] Surprisingly, Albert Ketèlbey’s (1875–1959) In a Persian Market is also missing. This six-minute light classical piece for orchestra and optional chorus, published in 1921, has been extremely widely performed, however, also in the context of comic oriental scenes, and therefore it should have been included in the discussion of other musical compositions associated with orientalism.

Another interesting orientalist work, which MacKenzie mentions only by name,[51] is Paul Dukas’ (1865–1935) La Péri, ‘the Flower of Immortality’, based on a Persian story and premièred in Paris 1912. The story tells of Prince Iskender in his search for the flower of immortality, which he then steals from the hands of a sleeping Péri (a female genie). The Péri proceeds to seduce Iskender and he is finally induced to return the flower that had held the promise of immortality for him. The role of the Péri was performed by Anna Pavlova (1882–1931) in the 1920s, for example in London, Paris and Buenos Aires.[52]

Dukas’ La Péri was performed by Ballet Rambert in 1931, choreographed by Frederick Ashton and with Alicia Markova (1910–2004) as the Péri. Ashton was inspired by Persian paintings that he saw at an exhibition at Burlington House. Ashton and Markova studied the paintings and gained ideas for both movement and make-up. Ashton borrowed the idea of groupings from Bronislava Nijinska’s (1891–1972) choreography Les Noces (1923), with music by Stravinsky. Ashton had recently worked with Nijinska in Paris at Ida Rubinstein’s ballet company, and William Chappell (1907–94), who made the design for La Péri, also danced there.[53]

Markova was the Péri and Ashton played Iskender with six female dancers. Mary Clarke writes about Ashton’s choreography in her history of Ballet Rambert: ‘He used also a corps de ballet of six girls, attendants of the Péri, and for them he devised strange, semi-oriental movements and groupings of surpassing beauty.’[54] Ashton’s biographer Julie Kavanagh writes: ‘To evoke the stiff, stylized groupings Ashton had seen at Burlington House, he borrowed the idea from Nijinska’s Les Noces, architecturally massing a corps of six girls, attendants on the Peri, into abstract constructivist pyramids.’[55]

La Péri was performed again in 1938 by the Ballet Rambert with choreography by the South African Frank Staff (1918–71), who also danced in the company. His choreography was made for ten women and one man. The Péri was danced by Deborah Dering, and Frank Staff was Iskender. Mary Clarke writes in her history of the Ballet Rambert: ‘he [Staff] used a corps de ballet for the first time but he did not succeed in effacing memories of the Ashton ballet and, despite its beautiful décor and costumes by Nadia Benois, this Péri was soon withdrawn.’[56]

The most interesting thing in the context of this research into Khadra, however, is that the Ballet Rambert Archive material reveals that Celia Franca, who danced at the company at that time, performed in this production as one of the Péri’s companions.[57] In all of the above-mentioned performances at the Ballet Rambert there was piano accompaniment, not orchestra.[58]

La Péri was also choreographed by Serge Lifar in 1946 for the Nouveau Ballet de Monte Carlo in the same year as Celia Franca’s Khadra.[59]

It should be mentioned that another Belshazzar’s Feast, William Walton’s (1902–83) oratorio was planned as a ballet in 1934, choreographed by Frederick Ashton, although this plan was never put into practice.[60] There are also earlier works with the name: an oratorio by Handel as well as Rembrandt’s painting Belshazzar’s Feast, at the National Gallery in London.

THE CHOREOGRAPHY OF KHADRA

Sibelius’s incidental music for Procopé’s play Belshazzar’s Feast is scored for flute (piccolo), two clarinets, two horns, various percussion instruments (bass drum, cymbals, tambourine and triangle) and strings. For the concert suite Sibelius added another flute (piccolo) and oboe. The oriental atmosphere is clearly discernible in the music; it is colourful and imaginatively orchestrated. This is apparent in all the musical numbers, especially in Oriental Procession and Khadra’s Dance. Below is a description of the four scenes of the ballet with the music from Belshazzar’s Feast as described by Honor Frost.

The ballet included also an overture, Sibelius’s Romance in C major, Op. 42 (1904), for string orchestra. Sibelius’s piece is romantically blooming music, tinged with darkness and elegantly singing, very much reminiscent of Tchaikovsky. Its duration is around four and a half minutes, during which an Old Man, a Sage, slipped out between the curtains and settled himself down in a chair reading a book.

According to Honor Frost: ‘The function of an overture is to put the audience into the right frame of mind for the journey they are about to make into an imaginary world. “Oriental” music is most frequently used on the stage and films to introduce the erotic and voluptuous. But this is not the mood of “Khadra”. The order, beauty, and benevolence of her world was introduced therefore by an old man, a Sage, who walked out from between the curtains and quietly settled down to read his book while overture played. He was a symbol of the peace and remoteness of the world behind the curtain, and when it went up he merged into the life of that world.’[61]

In the first scene, called Khadra’s Dance as in Sibelius’s suite, there are differerent characters and groupings on stage: Drum Boys, Flower Girls, Husband and Wife, etc. Khadra enters; her mood at the beginning of her dance is that of a wide-eyed child filled with a sense of wonder and unquestioning gaiety. She darts from group to group watching them, yet never taking part in their activities. She changes her mind and dances all around the stage. She spins, though made giddy by an excess of experiences. Exhausted at last, Khadra joins the old man: she falls asleep at his feet. All the others disappear from the stage.

Sibelius arranged the suite movement Khadra’s Dance from two separate musical numbers in the original theatre score. The first accompanies a ‘Dance of Life’ in which Khadra dances on roses and tiger skins; the duos of flute and clarinet alternate charmingly. The other dance is a ‘Dance of Death’: Khadra dances with a snake, which bites her; the sinous melody in the clarinet’s low register moves in a serpentine manner. For the suite Sibelius made an ABA structure, the Dance of Life returning at the end of the piece. Celia Franca’s choreography is totally different, however, and there is of course no snake in it.

In the second scene the Lovers appear on stage. The scene called The Lovers’ Dance is a pas de deux for the Lover and his Beloved. Frost explains: ‘The choreographer brings a quiet mood of tender lovemaking into the first part of the dance by keeping all the movements terre à terre, but when the music is repeated the mood develops and changes… The Beloved now leaves the ground – but always in a “lift”.’[62] In the original incidental music a Jewish girl is rowing a boat on the river and her melancholy song carries through the air to the palace. The song appears in the concert suite in a purely instrumental version entitled Solitude. The vocal part is played by solo viola and cello with an accompaniment of upper strings.[63]

In the beginning of the third scene, called Oriental Procession, little boys appear beating drums; they are following by other characters. Khadra is woken, she dances and Lovers are drawn into the dance. All three of them are encircled by the corps de ballet, and the Lover performs a virile solo. Finally all the others leave and Khadra is left alone. In Sibelius’s Oriental Procession, the arrival of the procession is depicted by an increase in dynamic level (crescendo). In this march we hear the beat of the bass drum, cymbals, tambourine and triangle. The strings’ quintuplets create an oriental atmosphere which is intensified by the woodwind solos and the piccolo’s shrill squeals. The departure of the procession is depicted by a decrease in dynamic level (diminuendo).

The original incidental music on which the Nocturne in Sibelius’s concert suite is based depicts night; the characters are observing the stars moving through the sky. The solo flute glitters like the stars above to an accompaniment from the strings. Like Sibelius’s Nocturne, the fourth and final scene of the ballet takes place at night, and is called Night Music. Khadra is again joined by the others, the Lovers and corps de ballet. The dancers form themselves into a tower-like group, like a pyramid. Khadra dances together with Lover and his Beloved, then leaves them and sleepily goes home to bed.

ON A PERSIAN CARPET IN ISLINGTON

There were many dancers involved in Franca’s choreography. The roles of the Lover and the Beloved were danced by Leo Kersley and the 15-year old Anne Heaton. The principal character, Khadra, was danced by Irish-born Sheilah O’Reilly (1931–2019), also 15 years old at the time.[64]

The choreography of Khadra was a challenge for the dancers, especially for the male dancers. In his memoir, the dancer Peter Wright (b. 1926) writes about Khadra: ‘The ballet was like a fragment of a Persian sculptural frieze coming to life. I had to lift a girl from a shoulder-height rostrum and carry her around the stage as she sat on my upraised hands above my head. That was quite a test of my partnering skills at the time.’[65]

Among the critics, especially the design of the ballet was praised. According to Sophie Basch, Honor Frost’s design was so impressive ‘that some critics feared that it overwhelmed the ballet itself.’[66] Frost was even compared to Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes designer Léon Bakst who had provided the scenery for such productions as Cleopatra (1909) and Scheherazade (1910). The Stage started its review with the sentence: ‘A popular title for “Khadra” might be “On a Persian Carpet”.’

‘The curtain rose to reveal a larger-than-life conception of a Persian oasis rich in vegetation familiarised by the carpets of Isphahan [city in Persia, today in Iran, famous for its carpets]. Honor Frost, who designed costumes and décor should have received the largest and most colourful of the many bouquets handed across the footlights. The scarlet-lacquered pavilion, the golf-leaf sky, the stylised flowering shrubs and varied flora sprouting from the pink sand, created a world as wondrous and luxuriant as any known to Scheherazade. The tasteful costumes seemed to embody every colour known to man. Far from clashing, they all harmonised to excite eye as vividly as the music of Sibelius fell on the ear. Celia Franca’s choreography hardly rose to the same inspired heights despite her attractive groupings. One expected rather more than a slight incident to occur in so exotic setting. With rare beauty, Sheilah O’Reilly, Anne Heaton and Leo Kersley translated attitudes born of the Orient into movement and happily blended them to music created in Finland. The ballet was a feast for the eye and should put Miss Frost well on the road to becoming the Bakst of her generation.’[67] [68]

The sumptuousness of the sets and costumes was achieved despite shortages at a time when everything related to clothing was rationed. Bishop-Gwyn writes: ‘Rationing was still in effect and Celia had to calculate the number of coupons necessary for costume yardage. She reckoned that for forty yards of wool stockinette, one hundred and eighty coupons were needed. She begged and borrowed coupons from whomever was around.’[69]

These obstacles, however, only flamed Honor Frost’s imagination. Khadra’s particularly imaginative costumes were cut from recycled materials.[70] Honor Frost writes: ‘All the costumes were made of a heavy, clinging wool stockinette, a material which is admirably suited to certain types of dancing, as it hangs well, yet the line of the body is never lost. This white stockinette was bought in bulk. Owing to post-war shortages, it was impossible to get it in colours; every inch of it was dyed and over a hundred colour blocks printed on it by hand… The head-dresses were made out of completely fanciful materials – plastic wire straw, cellophane-straw, horsehair etc., etc., and all the women’s “wigs” were made out of navy-blue stockinette.’[71]

Richard Buckle (1916–2001), who later wrote several books related to ballet, for example about Nijinsky (1971) and Diaghilev (1979) – wrote in his commentary in July:

‘The choice of Sibelius’ music was certainly a happy one, and some of the fantastic Persian dresses were splendid – though the intricate scenery was ill-conceived; there were some good groupings and movements, which seemed to derive partly from Fokine’s mock Oriental dances for the Queen of Shemakkan; but the general effect was one of romantic chaos. For most of the quarter of an hour which the ballet lasts, the stage is full of people, all dressed differently and all performing different movements; in spite of Khadra’s smile and of the languors of Leo Kersley and Anne Heaton, the white-clad lovers, the works lacks accent and construction… In all honesty I must say that after I have seen Khadra twice or three times, and now that I have read my programme, I may give a more favourable or at any rate a different report on it. More fortunate than the patrol leader, I get a second chance; and nothing much hangs on what I say one way or the other. Khadra was applauded with greater enthusiasm and noise than any other production of the recent French ballet [Ballet des Champs-Élysées] at the Adelphi. I am interested in applause. Apart from the applause due to the several merits of Franca’s work, the ovation accorded to Khadra was no doubt due partly to the “Happy Family” game traditionally played at Sadler’s Wells, partly to the variety of bright colours in the designs of Honor Frost, but chiefly, I am sure, to the sudden appearance of handsome Miss Franca and pretty Miss Frost, hand in hand, wearing striking evening dresses, and bowing humbly as they received a shower of bouquets.”[72]

Khadra was a success and stayed in the repertoire every season until summer 1952. There were altogether 48 performances in London at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre. The company also toured in the United Kingdom with Khadra.[73]

Sibelius’s music was conducted at the première by the English conductor Reginald Goodall (1901–90), who had joined the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in 1944. He had previously conducted Benjamin Britten’s opera Peter Grimes there in 1945. After Reginald Goodall the following seasons’ conductors of Khadra were Ivan Clayton (1946–47), Harry Plats (1947–48), Guy Warrack (1948–51) and Norman Tucker (1951–52).[74]

AFTER THE SUCCESS OF KHADRA

At the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet Celia Franca’s following choreography – Bailemos, using Jules Massenet’s music Le Cid and premièred on 4 February 1947 with sets and costumes by Honor Frost – proved to be far less successful. During the spring of 1947 it was performed eleven times and after that it disappeared from the repertory.[75]

After making these two choreographies for the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet, Franca joined the Metropolitan Ballet in 1947. She also choreographed for television: Dance of Salome (1949, music by James Hartley) and Eve of St Agnes (1950, music by John Lanchbery), which was commissioned by the BBC.[76] In 1951 she worked again with Honor Frost and choreographed Colloque Sentimental, poems by Verlaine set to music by Debussy with Frost’s decor and costumes for Ballet Rambert at the Mercury Theatre.[77] In 1950 Celia Franca received an invitation from Canada to establish a ballet company; the following year she moved to Toronto and the new organization became the National Ballet of Canada. When Franca passed away in 2007 at the age of 85, she was honoured in the press: ‘She taught Canada to dance’.[78] The Celia Franca Foundation was established in 1979 to honour her devotion to quality dance education in Canada.[79]

The designer Honor Frost made sets and costumes for the Ballet Rambert in the yearly 1950s and soon after that dedicated herself to sea archaeology, the discipline in which she became world-famous and which earned her the epithet ‘the diving diva’. In 1947 her drawings for Khadra were exhibited alongside work by other painters and scenographers for a retrospective entitled Background to Ballet at an art gallery in Mayfair.[80] The following year her book How a Ballet is Made was published, a slim volume dealing only with Khadra. The hard-to-find book is in itself a work of art, a valuable addition to the Sibelius literature.[81] [82]When Honor Frost passed away in 2010 at the age of 92, she bequeathed the proceeds of the art collection left for her by her guardian Wilfrid Evill to fund maritime research in the eastern Mediterranean. Its value was enormous: the £41 million it obtained at auction in 2011 exceeded all expectations. Today the Honor Frost Foundation awards research grants for maritime archaeology.[83]

SEA CHANGE

‘Sea change is an English idiomatic expression which denotes a substantial change in perspective, especially one which affects a group or society at large, on a particular issue. The term originally appears in William Shakespeare’s The Tempest in a song sung by a supernatural spirit, Ariel, to Ferdinand, a prince of Naples, after Ferdinand’s father’s apparent death by drowning.’[84]

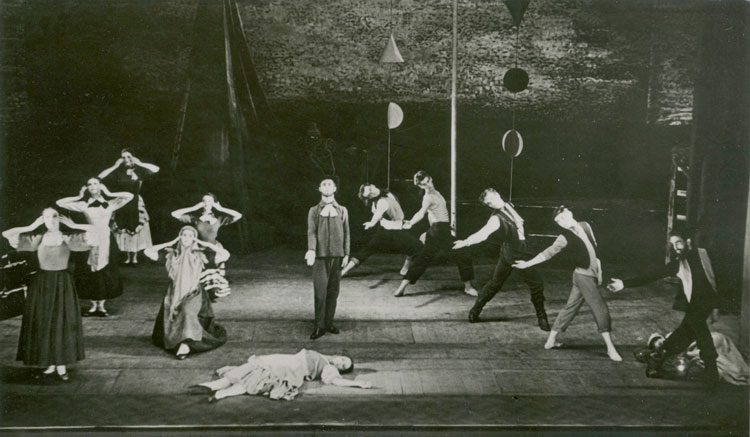

Sea Change was a choreography by John Cranko (1927–73) to the music of Sibelius’s tone poem En saga, Op. 9 (1892/1902), with design and costumes by John Piper. It was premièred during Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet’s tour in Dublin on 18 July 1949 at the Gaiety Theatre. In the Dublin programme there is a line characterising Sea Change which is from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: ‘Nothing of him that doth fade; But doth suffer a sea change; Into something rich and strange’.[85]

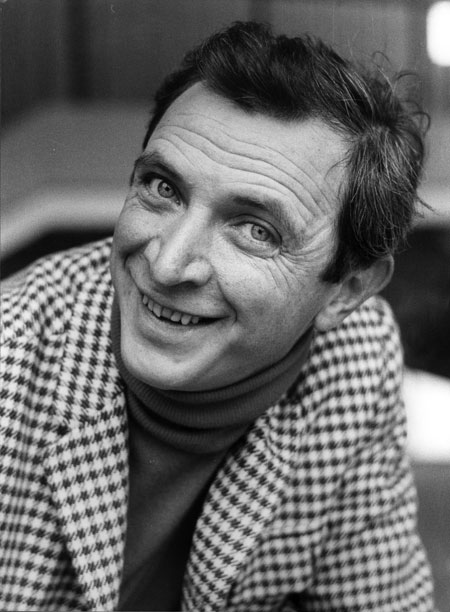

JOHN CRANKO

John Cranko was born in South Africa in 1927 and received his early ballet training in Cape Town. In 1945 he choreographed his first work using Stravinsky’s suite from L’Histoire du Soldat for the Cape Town Ballet Club. He arrived in London in 1946 to continue his dance studies at Sadler’s Wells Ballet School, and shortly afterwards he became a member of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet.

He was able to join the company because George Gerhardt, one of its few experienced male dancers, was leaving. One of the roles created for Gerhardt was the Husband in Celia Franca’s Khadra. ‘He had to catch Anne Heaton from a platform at shoulder height, raise her above his head and lower her gently. The sequence was made to measure for Gerhardt who, in Heaton’s phrase, was “built like a tank”. He also had to lift Sheilah O’Reilly in a “lotus position” above his head. The young men at Sadler’s Wells had neither the strength nor training for that sort of feat. But in South Africa, because male dancers were scarce, even the most rudimentary beginners were taught partnering. Cranko asked whether he could have the vacant post provided that he could manage those lifts. He rehearsed and obtained the job, unfortunately at the cost of giving himself a hernia for which he needed hospital treatment.’[86]

John Cranko

© Hannes Kilian, courtesy Stuttgart Ballet

Peter Wright, too, noted that Khadra was ‘a test for his partnering skills’.[87] Cranko danced the role of the Husband in Khadra in the season 1946–47. He was also one of the Nobles in Franca’s next choreography, Bailemos, in the spring of 1947.[88]

In the beginning of season 1947–48 Cranko was transferred to the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, Covent Garden, to give him more chances to work as a dancer with experienced choreographers. He took small parts in ballets by Frederick Ashton, Ninette de Valois, Robert Helpmann and Leonide Massine.[89] Dancing in both these companies gave him the opportunity to make choreographies for the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet. He undertook some choreographies for the company and also outside, for instance the revue Calypso (for a small company called St James Ballet) and The School of Nightingales with music by Couperin (1948).[90] Sea Change was, however, Cranko’s first major choreography for this company.[91]

BACKGROUND TO THE CREATIVE WORK; CHOOSING MUSIC AND DESIGN

Cranko’s biographer John Percival writes that the first inspiration for Sea Change came in 1947, from the attraction that the sea and the fishermen’s lives exercised on the choreographer during his holiday in Cassis. The small fishing village by the Mediterranean, not far from Marseille in southern France, had inspired many artists such as Paul Signac (1863–1935), André Derain (1880–1954), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Georges Braque (1882–1963) and Raoul Dufy (1877–1953).

From Cassis Cranko wrote a letter to his friend Hanns Ebenstein: ‘I can’t begin to write it all down, it’s so lovely. One sees at a glance all the blue period of Picasso – the wild horses of Chirico – the extraordinary landscapes of Dali – the Italian primitives – Botticelli. Colour intensifies, the sun dries out all the sogginess of the soul. The air glitters like diamonds and the night air is like warm honey… Tonight we are going fishing. God bless us every one!’[92]

He wrote that ‘all the activity on the beach had a great fascination for me – the nets hanging out to dry, people mending them, various types standing round watching, all the usual incidents that happen in a fishing village. Certain movements such as boys kicking football gave me ideas for the choreography.’[93]

These sunny Mediterranean pictures from his holiday soon disappeared from his choreography plans. Earlier, however, in South Africa in 1945, he had bought records of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition and planned ‘a large and sumptuous ballet on fisherman and his soul, for which I shall use the Moussorgsky.’ Percival writes that this plan never came to fruition,[94] but it suggests that the fisherman as a potential topic was already in his mind.

Percival writes: ‘Having to use existing music, John considered several possible scores, all of which were rejected as unsuitable for one reason or another. Among the rejected choices was Sibelius’s Tapiola [Op. 112, 1926], and at that stage in planning, the story was to have been of “a rather simple girl who hangs about on the outskirts of a village… She finds a fisherman who has been washed up on the shore. She revives him and looks after him until he gets strong. During this time he becomes all the world to her, and he is grateful but unaware of her affection. When he is completely recovered, he sees some other villagers and returns to the world he knew, leaving the girl to her solitary existence.” When he rather reluctantly accepted the suggestion of another Sibelius score, En saga, he found that “the music suggested rather a different story.”’[95]

In his memoirs Peter Wright, who danced in Sea Change as one of the fisherfolk, writes: ‘Sea Change was not at all bad even though its score, En saga by Sibelius, was his 15th choice before Madam [Ninette de Valois] would let him do that early ballet.’[96]

The story of the ballet ‘eventually showed fishermen preparing and setting out on a peaceful evening for a night’s work; while they are at sea, a storm blows up. The women wait anxiously and when the boat returns one of its crew has been lost, causing inconsolable grief to his young wife. It was a simpler and a better story [than Tapiola].’[97]

For Cranko, choosing a designer was obviously easier than choosing the music. John Piper was already a famous artist at the time. Cranko was already familiar with his works before leaving Cape Town and thought highly of them, although only from reproductions.[98] According to Piper’s wife Myfanwy there were two people he had considered when in South Africa and with whom he wished to collaborate: Benjamin Britten and John Piper.[99] Ninette de Valois put Cranko in touch with Piper in 1948 and Cranko asked him to provide the scenery for the ballet.[100] Piper had previously designed two ballets, one for Frederick Ashton and another for Ninette de Valois. Most of his earlier stage designs had been for opera.[101]

Myfanwy Piper writes: ‘Sea Change is a sad little tale of a joyful departure of the fishermen and their farewell to their families, a dance of tragic anticipation for the wives and families during a storm, and the return of the men without one of their number and the breaking of the news to his pregnant wife. Cranko had difficulty is [=in] finding the right music for this ballet – it was not to be a commissioned work – and the final choice of Sibelius’ En saga was not particularly interesting or very easy for him to work to. But the rich simplicity of the set, red, black and dark blue, the peasant-like awkward movements of the fisher folk and the touching reality of their simple emotional relationships gave an extraordinarily moving quality to a work that was in some ways raw and stilted.’[102]

OTHER SEA INFLUENCES

John Percival suggests that the dark mood of Sea Change was at least partly influenced by Benjamin Britten’s (1913–76) opera Peter Grimes ‘which also included episodes of fishermen mending their nets’.[103] This influence might be possible. Peter Grimes was premièred in 1945 at Sadler’s Wells, and it was also performed at the Royal Opera House in 1947. As Cranko arrived in London in 1946, he would surely have seen the work at Covent Garden.

Peter Grimes is set in a Suffolk coastal village in the mid-19th century. The principal character Peter Grimes is a fisherman who is blamed for the death of his apprentice at sea. Later John Piper introduced Cranko to Benjamin Britten and they worked together on several productions, starting in 1953 when Cranko staged dances to Britten’s new opera Gloriana with Piper’s design at the Royal Opera House.[104]

There might, however, be another source as well: the Irish writer John Millington Synge’s (1871–1909) works about the rural people in the Aran Islands and his play Riders to the Sea, premièred in Dublin in 1904. The play deals with the hopeless struggle of people against the impersonal but relentless cruelty of the sea.

The sea is a central element in other operas too, including Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. After his opera Debussy composed La Mer (1905), an impressionistic work dedicated to the sea. Many British composers have composed music related to sea: Edward Elgar’s Sea Pictures (1899), Vaughan Williams’s Sea Symphony (1909) and Frank Bridge’s The Sea (1911).

Constant Lambert (1905–51) – composer, conductor and music director of Sadler’s Wells Theatre since 1931 – wrote in his book Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline in 1934: ‘Whereas in most works of art inspired by the sea, Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony, for example, we are given the sea as a highly picturesque background to human endeavour and human emotion, a suitable setting for introspective skippers, heroic herring fishers and intrepid explorers, La Mer is actually a picture of the sea itself, a landscape without figures, or rather a seascape without ships.’[105]

Sibelius himself wrote several works related to sea, for example the incidental music to Pelléas et Mélisande, Op. 46, in which one of the numbers in the orchestral suite is named By the Sea (1905), and Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Op. 109. His work with the most obvious connection to the sea is the tone poem The Oceanides, Op. 73 (1914). His early sea-inspired chamber music includes the Trio in A minor, ‘Havträsk Trio’ (JS 207, 1886) and Trånaden (Yearning) for recitation and piano (JS 203, 1887), both composed in Korpo.

SIBELIUS’S EN SAGA

The orchestral work En saga, Op. 9, was composed in 1892 and revised in 1902, with its origins in a projected Ballet Scene No. 2, which Sibelius had intended to compose as an octet for strings, flute and clarinet while studing in Vienna in 1890–91. In 1892 he wrote that Ballet Scene No. 2 ‘is just like a saga in the romantic style, 1820.’

Many suggestions have been made about the work’s inspiration. The Swedish title En saga suggests the Eddas but in connection with the composition of the piece Sibelius referred to the painter Arnold Böcklin: his gloomy forests, symbolic white swans and the Isle of the Dead. Sibelius later dissociated himself from all literary and artistic interpretations, remarking: ‘En saga is an expression of a state of mind.’[106]

En saga is dark, dramatic music, impassioned and with archaic features. Its introduction is bathed in primeval twilight; the woodwind monotonously intone a humming motif of narrow compass.

Sibelius’s biographer Erik Tawaststjerna has discussed tragedy and ballet in the context of En saga: ‘Sibelius persistently repeats melodic figures and motifs with falling seconds, creating a suggestive mood of magic and sorcery… The concluding tragedy is anticipated by four muted violins, ppp… The final culmination is almost frightening in its acute drama. The final motif of the ballad-like counter-subject laments in the oboes… Everything moved towards silence… Personally I have always felt that En saga would be most suitable for a ballet. The rhythmic nerve and the tragico-lyrical episodes of the tone poem undeniably produce scenographic associations…’[107]

OTHER CHOREOGRAPHIES: EN SAGA AND TAPIOLA

Tawaststjerna mentions a choreography of En saga named Poème by George Gé (1893–1962) at the Finnish National Ballet in 1931, but not Cranko’s Sea Change. George Gé’s Poème was the first choreography to Sibelius’s music in the company’s repertoire and En saga was later choreographed by Elsa Sylvestersson (1924–96) as well, with the name Satu (the tone poem’s name in Finnish).[108]

Outside Finland En saga has been choreographed not only by Cranko but also by the Australian ballerina Laurel Martyn (1916–2013), who made a version in 1936 in London, where she was studying ballet. It was performed at a charity matinée organized by Lady Moyne, and Moyne’s daughter Grania Guinness was the lead dancer. It was conducted by Malcolm Sargent, who tried to convince Laurel Martyn to choose an easier score. The performance was not successful – ‘a disaster’ – but it was a very good learning experience. She returned to Australia in 1939 and joined the Borovansky Ballet for which she reworked En saga. Her best-known work, this premièred in 1941 in Melbourne. It is a war story; the choreography was heavily based on character dance and the female performers wore character shoes.[109]

Percival writes that Cranko knew this choreography while creating his own to En saga: ‘The music finally chosen helped greatly in creating a sombre mood, but John did not find it interesting or easy to work with. He closely questioned Charles Lisner, who had come from Australia to join the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, about a ballet which Laurel Martyn had made for the Victorian Ballet Guild using that score: her subject matter, general treatment and what Lisner thought of the ballet.’[110]

It is interesting that another Australian ballerina, Joanna Priest (1910–97), chose Sibelius’s Tapiola – the composition that Cranko had considered but rejected – in 1947 for her choreography Winter Landscape. Priest had studied with Marie Rambert in London from 1930 until 1932. Back in Australia she made Winter Landscape for the Studio Ballet Theatre; it was performed in Adelaide in 1947.[111]

Sibelius’s En saga was performed again at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London when David Bintley (b. 1957) used it in his choreography The Swan of Tuonela, a ballet featuring many different compositions by Sibelius, in 1982.[112]

PREMIÈRE IN DUBLIN

In 1949 Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet started its summer tour of the United Kingdom and Ireland in Belfast and Dublin.[113] When the company was playing at the Theatre Royal in Hanley, Staffordshire England in June, the theatre caught fire, while Sea Change was in preparation.[114] [115]

Sea Change was premièred at the Gaiety theatre in Dublin on 18 July 1949. The Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet performed there for two weeks, starting on Monday 11 July, giving nightly performances and also matinées on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The programme also included Act II of Le Lac des Cygnes – with Elaine Fifield as Odette and David Poole as Prince Siegfried – and Frederick Ashton’s choreography Façade to music by William Walton. All the performances were conducted by the Scottish composer and conductor Guy Warrack (1900–86), who worked with the company during the period 1948–51.

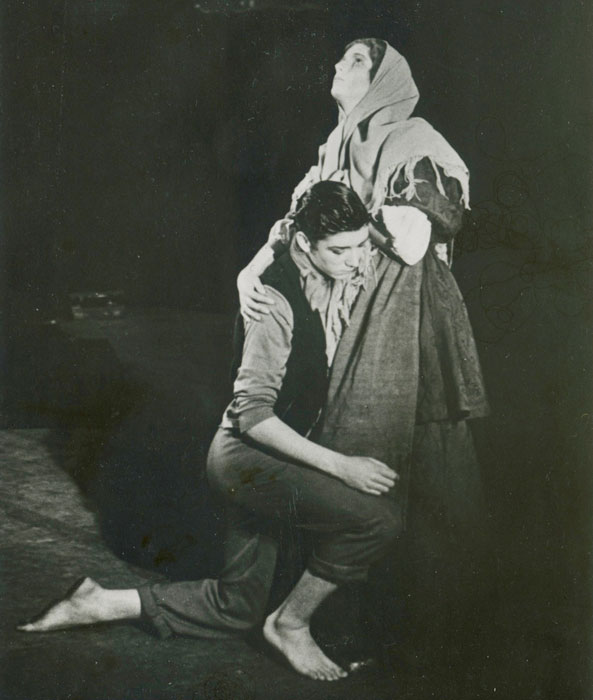

In Sea Change there were roles such as The Skipper (danced by David Poole), His Wife (Joan Cadzow), The Fisherman (Michael Hogan) and His Young Wife (Sheilah O’Reilly). There were also dancers depicting Fisherfolk and the Pastor.[116]

There were South African dancers in the company, among them David Poole and Maryon Lane (one of the Fisherfolk). The Fisherman’s Wife, who lost her husband at sea, was Sheilah O’Reilly. She had performed the role of Khadra, among others, and ‘was beginning to attract attention in dramatic roles but had never been given such an opportunity for anguished emotion, and she rose to it whole-heartedly.’[117] O’Reilly had to finish her dance career some years later after suffering an injury. She subsequently moved to France and taught ballet there.[118]

John Percival writes about Sea Change: ‘The ballet had some rough edges to its structure and the groupings, like the emotions, were sometimes a little too obviously contrived, but it marked a step forward for its choreographer in its attempt to achieve dramatic seriousness and depth.’[119]

It should be noted that the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet’s performance in Dublin took place only a few years after the end of World War II, and the circumstances were still poor and precarious (cf. the situation with the costume fabrics for Khadra). The Gaiety Theatre announced in the programme booklet: ‘This Theatre is Disinfected throughout with Jeyes’ Fluid.’

After Dublin the company performed Sea Change in London, starting on 27 September 1949.[120] The review in The Stage referred to Peter Grimes and labelled it as one of the richest jewels in the company’s crown:

‘The atmosphere of Peter Grimes is recalled as the curtain raises on this new ballet to the En saga music of Sibelius, revealing the crew of hardy fishermen about to put out to sea from their rough stone breakwater. “Men must work and women must weep” and, left alone on the waterfront throughout the violence of the ensuing storm, the womenfolk sink into the depths of despair concerning their loved ones at sea… as the mariners return one by one, to the relief of their waiting mothers and wives. The suspense is almost unendurable, only shattered by the outbreak of wild hysteria on the part of the young wife whose husband is claimed by the sea. Surrounded by figures arrested in static attitudes of grief and dejection Sheilah O’Reilly danced the role with stirring tragic force. John Piper has painted a decorative back-cloth suggesting how completely fisherfolk are at the mercy of the elements. His dark brooding sea of many secrets strikes the same note as the wild music of Sibelius. John Cranko has expounded this intensely dramatic episode in bold movement, which portrays the strong emotions of these primitive people in a ballet of unforgettable power and poignancy… is one of the richest jewels in the crown of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet.’[121]

Postcard; photo by O’Callaghan

So far, everything Cranko had produced in London had been light-hearted (e.g. Tritsch Tratsch to music by Johann Strauss), but Sea Change was a complete contrast in mood.[122] The review by Richard Buckle, who was then ballet critic for the Observer (1948–55), reveals the atmosphere of the ballet compared to Cranko’s previous choreographic works:

‘MR JOHN CRANKO, whose Muse I believe to be a gay and sprightly creature, is perhaps going through one of those dark, brooding periods common to intelligent young men, and his new ballet, SEA CHANGE, given at Sadler’s Wells on Tuesday, is about humble folk who go out fishing and get drowned in appalling weather leaving their girl-friends behind them. Such themes are well matched by the music of Sibelius – “En saga” in this case – and by John Piper’s black and tragic style of landscape painting. Cranko is choreographically inventive, he sets his steps to music in a way that shows the music means something to him, and he has the taste to know what will and what will not look right on the stage: in fact he is a good choreographer and he has made a success of this work. That I think his theme unsuitable to a one-act piece I will not deny, and I hope that from the dark waters of the psychological ballet he will be one of the fishermen who return safely home. The company, which had obviously been thoroughly rehearsed, gave a fine performance… Intensive interpretation of the music by Mr Warrack who had given a fine rendering of Sea Change robbed this last ballet [Carnaval, choreography by Fokine] of much of its delicate charm.’[123]

There is a cartoon of Sea Change by Ronald Searle, made for Punch, of the final scene depicting the Young Wife lying on the ground and others around her.[124] John Piper’s drawing of the set design with red, black and dark blue colours is in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection and can be seen online (click here).

There were 13 performances in London during the 1949–50 season, and the following season Cranko took the trouble to work on it further, ‘eliminating the somewhat superfluous role of a pastor, for instance, and putting the women into soft shoes instead of point shoes so that the movement looked more natural.’[125] There were the same number of performances that season, the last one being on 5 June 1951.[126]

After that it disappeared from the repertory of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet. Sea Change was, however, performed by University of Cape Town Ballet in 1952, together with Cranko’s Beauty and the Beast (to Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite) staged by David Poole. Cranko allowed the company to have the works without any payment, in gratitude for the help he had received when he was young.[127]

CRANKO AND MUSIC

After Sea Change, Cranko continued his choreographic work in England in the 1950s. Thanks to their collaboration in Sea Change, Piper became an important person for Cranko. Percival writes: ‘Offstage, too, the Pipers became like second parents to John, and he picked up from their example many influences on his daily life as well as art. They affected his taste in food, for instance, his liking for antiques – even, one friend thought, the way he walked.’[128] Piper made several sets and designs for his choreographies, such as Harlequin in April (1951), The Shadow (1953), The Prince of the Pagodas (1957) and Secrets (1958).

Following prosecution for homosexuality Cranko relocated to Stuttgart where in 1961, at the age of thirty-three, he became director of the city’s ballet company, which he developed into a world-class ensemble. Cranko’s career ended when he died unexpectedly in at the age of 45 on a return flight back to Stuttgart from a successful tour in the United States in 1973. The plane made an emergency stop in Dublin, where he was pronounced dead. (In the end, he did not return safely home, like the fisherman in his choreography). In 1971 he had opened the Stuttgart Ballet School, which after his death was renamed the John Cranko School. There is also a John Cranko Society which presents the John Cranko Award every year. His choreographies are performed by ballet companies all around the world.

All the previous comments about Sea Change show that choosing music for his choreography was difficult for Cranko, and Sibelius’s En saga was suggested to him. He was not particularly interested in choreographing a composition by Sibelius. It should also be noted that Cranko had not received musical training so his musical knowledge came from recordings.[129] Despite that, as John Percival writes, his choreographies were skilfully planned from a musical point of view.[130] As early as 1947 his Morceaux enfantins to Debussy’s music was praised, especially ‘the sensitivity with which Cranko had matched movement to music’.[131]

TOURING IN CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES

In the autumn of 1951 the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet travelled to North America, a tour organized by the American impresario Sol Hurok (1888–1974), who had also organized the two tours for the Covent Garden ballet company in 1949–50 and 1950–51.[132]

Hurok writes about the performances he saw during his visit to London: ‘Celia Franka [Franca] had an interesting work, Khadra, to a Sibelius score, with charming Persian miniature setting and costumes by Honor Frost. The young South African John Cranko, who had been a member of the Covent Garden company in the first New York season, had a number of extremely interesting works, including Sea Change…’[133] For the tour he chose Khadra but not Sea Change. He thought that Sea Change was moving but he ‘never felt that music and movement quite came together’.[134]

Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet travelled to Canada and the United States in September 1951 and the tour lasted twenty-two weeks, until April 1952.[135] The orchestra was from New York, named ‘American Sadler’s Wells Orchestra’, and was the same ensemble that had performed for the Covent Garden company’s two American seasons.[136] It was conducted by John Lanchbery (1923–2003) and the American Robert Zeller (1919–82).[137] Lanchbery had just joined the company (with which he worked from 1951 until 1959); Robert Zeller had conducted De Basil’s Ballet Russe in the late 1940s and other European ballet companies when they were on tour in America.

After the company had performed in Los Angeles, it travelled to the next city by train. In his memoirs Peter Wright relates: ‘Next was a long trek, three days and two nights, across the Arizona desert on board a 13-car train to San Antonio in Texas. This was pretty eventful! Back in London but aware of the itinerary, Madam [Ninette de Valois] worried about the rather randy American orchestra that was travelling with us. We were not allowed our own musicians because of union restrictions. The orchestra travelled in separate coaches but Madam was very concerned about our young girls. She insisted that the connecting door between the dancers’ section and the orchestra was to be kept locked, presumably to prevent her girls being deflowered. Anyway, within half an hour out of Los Angeles the lock was picked and life became more interesting…’[138]

The tour ended in New York, where the company performed at the Warner Theatre as the Metropolitan Opera House was not available, as the current opera season was not yet over.[139] The New York Times announced the visit of the company in an article with the headline: ‘Theatre Ballet Unit performs Khadra’.[140] The tour was a great success, both artistically and financially, according to its impresario Hurok ‘breaking box-office records for ballet in many cities’.[141]

John Cranko’s Sea Change disappeared from the company’s repertoire after Hurok had rejected it for touring. After the company returned to London there were four performances of Celia Franca’s Khadra in June 1952, after which this too disappeared from the repertoire. Khadra had been a real success, however, having been performed as a popular ballet in six seasons during the first years of the company’s existence.

Mary Clarke writes in her history of the company: ‘The American tour 1951–52 completed the process of turning the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet into a completely professional company with a distinct personality and assurance.’[142]

SIBELIUS, CELIA FRANCA AND JOHN CRANKO

There is no mention of these choreographers or choreographies in the Sibelius book by Santeri Levas, who was Sibelius’s private secretary in his later years.[143] It would be interesting to know if Sibelius knew about these ballets, as he was familiar with dance.

Why did these two young dancers and choreographers, Celia Franca and John Cranko, choose Sibelius’s music? Undeniably Sibelius’s reputation was high in the UK; his music was performed in concert and had also been used in earlier ballets.

It might be, however, that both Franca and Cranko were influenced by Constant Lambert. The influence might have been direct or indirect, through middlemen or in this case a middlewoman, Ninette de Valois.

Lambert conducted Sibelius in concert, and in his book Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline, he championed Sibelius strongly. He mentions Sibelius’s En saga in connection with his other symphonic poems, such as The Oceanides and Tapiola.[144] He also refers to other compositions related to the sea, such as Debussy’s La Mer and Vaughan Wlliams’s Sea Symphony.[145] Lambert also writes about exoticism in music, and refers to Persia and Glinka’s opera Ruslan and Ludmilla.[146] He does not mention Sibelius’s Belshazzar’s Feast, but refers to Walton’s oratorio of the same name.[147] As Stephanie Jordan has clarified, Lambert was a central figure in suggesting and choosing music for Frederick Ashton’s ballets.[148] Ashton even had a plan (which was never realised) to make a choreography to Sibelius’s Seventh Symphony.[149]

In his book Lambert writes: ‘Of all contemporary music that of Sibelius seems to point forward most surely to the future. Since the death of Debussy, Sibelius and Schönberg are the most significant figures in European music, and Sibelius is undoubtedly the more complete artist of the two.’[150]

After these works neither Celia Franca nor John Cranko choreographed any music by Sibelius. Cranko was not inspired in the early stages of choreographing his Sea Change with En saga. A few years after the première, however, Otto Friedrich Regner wrote an appreciation of Sea Change in Das Ballettbuch (1954). He compares the young Cranko to Leonide Massine, George Balanchine and Serge Lifar when these famous choreographers were in their twenties: ‘You could feel that he represented a new choreographical style… [Cranko] does not use clichés and does not bend to convention. The plot is balladesque… One of the wives experiences now the destiny that constantly threatens all of them [the fishermen and their wives]. A moving story, a moving ballet which, however suffers because Cranko rather coyly makes a compromise between what is realistic and what is balletic.’[151]

George Balanchine (1904–83) wrote a book about great ballets, including Giselle, The Nutcracker, Romeo and Juliet, Scheherazade and Swan Lake. He chose one choreography made to Sibelius’s music: Khadra.[152]

© Eija Kurki 2021

Eija Kurki (b. 1963) published her dissertation Satua, kuolemaa ja eksotiikkaa. Jean Sibeliuksen vuosisadan alun näyttämömusiikkiteokset (Fairy-tale, Death and Exoticism. Jean Sibelius’s Theatre Music from the Beginning of the 20th Century) in 1997 at the University of Helsinki and has subsequently continued her research, uncovering much previously unknown information about the plays, Sibelius’s fascinating scores and their performance history, writing numerous articles in various specialist publications both in Finland and internationally (e.g. Sibelius Studies, Cambridge University Press, 2001). She has written the booklet notes for several world première recordings of Sibelius’s music on the BIS label, texts that have won praise from leading Sibelians such as Robert Layton. In November 2024 she published, together with Professor Karl Toepfer from San Francisco, the most comprehensive study of Sibelius’s tragic pantomime Scaramouche, comprising 170 pages.

Since 2017 she has also been researching the Swedish-born theatre composer Einar Nilson (1881–1964), his life and work with director Max Reinhardt.

Sources

ARCHIVES

Royal Opera House collection, online

Victoria and Albert Museum Collection, online

University of Limerick, Digital Library

Finnish National Opera and Ballet Archive, online

The Ballet Rambert Archive, online https://www.rambert.org.uk/

https://theaterencyclopedie.nl/wiki/walter_gore

LITERATURE

Balanchine, George 1968 (1954): Balanchine’s New Complete Stories of the Great Ballets. Edited by Francis Mason. Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York

Basch, Sophie 2019: ‘Honor Frost, true to Herself: from art and ballet design to underworld archaeology’ in In the footsteps of Honor Frost. The life and legacy of a pioneer in maritime archaeology, edited by Lucy Blue. Sidestone Press, Leiden. pp. 39–90

Beaumont, Cyril W. 1951 (1937): Complete Book of Ballets. Putnam. London

Beaumont, Cyril W. 1952 (1942): Supplement to Complete Book of Ballets. Putnam. London

Bishop-Gwyn, Carol 2011: The Pursuit of Perfection. A life of Celia Franca. Cormorant Books Inc. Canada

Blue, Lucy (ed.) 2019: In the footsteps of Honor Frost. The life and legacy of a pioneer in maritime archaeology. Sidestone Press. Leiden

Bremser, Martha (ed.) 1993: International Dictionary of Ballet. Volume I A-K and II L-Z. St James Press

Brissenden, Alan – Glennon, Keith 2010: Australia Dances: Creating Australian Dance 1945–1965. Wakefield Press

Clarke, Mary 1955: The Sadler’s Wells Ballet. A History and Appreciation. The Macmillan Company. New York. Universal Digital Library

Clarke, Mary 1962: Dancers of Mercury: the Story of Ballet Rambert. Adam and Charles Black. London

Crisp, Clement – Gore, Walter – Hilton Gore, Paula 1988: The Life and Work of Walter Gore: A Tribute in Four Parts: I. Crisp: Introduction, pp. 3–6, II. Gore: Up till now, pp. 7–16; Hilton Gore: III. Walter Gore, pp. 17–22; IV. Walter Gore’s choreographies, A first listing pp. 23–29. In Dance Research: The Journal of Society for Dance Research. Vol. 6 No. 1 (Spring 1988). Edinburgh University Press

Crisp, Clement 2005: ‘Le Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas’ in The Journal of Society for Dance Research. Vol. 23 No. 1 (Summer 2005). Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–17

Croome, Angela 2014: ‘Frost, Honor Elisabeth (1917–2010), marine archeologist’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford. Published online, 9 January 2014 https://www.oxforddnb.com/

Dahlström, Fabian 2003: Jean Sibelius. Thematisch-Bibliographisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke. Wiesbaden-Leipzig-Paris. Breitkopf & Härtel

Frost, Honor 1948: How a Ballet is Made. Photographs by Churton Fairman and Roger Wood. Ballet Series No. 1. Golden Galley Press Ltd. London

Gruen, John 1975 (1970): The Private World of Ballet. The Viking Press. New York

Hurok, Sol 1953: S. Hurok Presents. A Memoir of the Dance World. Hermitage House. New York

Jordan, Stephanie 2000: Moving Music: Dialogues with Music in Twentieth-Century Ballet. Dance Books. Cecil Court. London

Kavanagh, Julie 1997 (1996): Secret Muses. The life of Frederick Ashton. The first paperback edition (with corrections) Faber and Faber

Kilpeläinen, Kari 1996: En saga, Op. 9 (booklet text) in Jean Sibelius: Symphony No. 5 in E flat major (original 1915 version), En saga, Op. 9 (original 1982 version). BIS-800. BIS Records AB, Åkersberga

Koegler, Horst 1987 (1982): The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Second Edition, updated 1987. Oxford University Press

Kurki, Eija 1995: Belshazzar’s Feast (booklet text) in Jean Sibelius: Jedermann, Op. 83 (Jokamies/Everyman); Belshazzar’s Feast, Op. 51 (Original Score); The Countess’s Portrait. BIS-735. BIS Records AB, Åkersberga

Kurki, Eija 2001: ‘Sibelius and the theater: a study of the incidental music for Symbolist plays”. in Sibelius Studies, edited by Timothy L. Jackson and Veijo Murtomäki. Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–94

Kurki, Eija 2019a: ‘Exoticism, snake dances, violin playing and ghosts. Eija Kurki discusses Sibelius’s music for the plays “Belshazzar’s Feast” and “The Lizard”.’ Sibelius One Magazine 01/2019. pp. 16–25. Also available online https://sibeliusone.com/music-for-the-theatre/

Kurki, Eija 2019b: ‘The Language of the Birds. Theatre music that cost of lot of effort but was never performed’. Sibelius One Magazine 07/2019. pp. 7–24. Also available online https://sibeliusone.com/music-for-the-theatre/

Lambert, Constant 1934: Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline. Second Edition. Faber and Faber Ltd, London

Levas, Santeri 1992 (1957/1960): Muistelma suuresta ihmisestä (Nuori Sibelius/Järvenpään mestari) WSOY. Porvoo-Helsinki-Juva

MacKenzie, John M. 1995: Orientalism. History, theory and the arts. Manchester University Press

Minors, Helen Julia 2009: ‘La Péri, poème dansé (1911–1912): A Problematic Creative-Collaborative Journey’ in Dance Research. The Journal of the Society for dance Research. Vol. 27, No. 2. Les Ballets Russes Special Volume Part 2. In Celebration of Diaghilev’s First Ballet Season in Paris 1909 (Winter 2009). pp. 227–252

Percival, John 1983: Theatre in My Blood. A Biography of John Cranko. Herbert Press

Piper, Myfanwy 1954: ‘Portrait of a Choreographer’. In Tempo, New Series, No. 32 (Summer 1954). Cambridge University Press, pp. 14–23

Rebling, Eberhard 1980: Ballett A-Z. Henschelverlag. Kunst und Gesellschaft. Berlin

Regner, Otto Friedrich 1954: Das Ballettbuch. S. Fischer Verlag

Tawaststjerna, Erik 1986: ‘En saga, Op. 9, first version 1983, revised 1902’ (booklet text) in Jean Sibelius: Scènes Historiques, Suite Op. 25 & Op. 66, En saga, Op. 9. BIS-295. BIS Records AB, Åkersberga

Tawaststjerna, Erik 1989 (1965): Jean Sibelius 1, toinen uudistettu painos. Otava

Vaughan, David 1999 (1977): Frederick Ashton and his ballets. Second revised Edition. Dance Book. Cecil Court. London

Vienola-Lindfors, Irma – af Hällström, Raoul 1981: Suomen Kansallisbaletti 1922–1972. Musiikki Fazer. Helsinki

Wearing, J.P., 2014a: The London Stage 1940–1949: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel. Rowman & Littlefield

Wearing, J.P., 2014b: The London Stage 1950–1959: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel. Rowman & Littlefield

Wicklund, Tuija 2014: Jean Sibelius’s En saga and Its Two Versions: Genesis, Reception, Edition, and Form. Academic dissertation. University of the Arts Helsinki, Sibelius Academy. Studia Musica 57. Unigrafia. Helsinki

Wright, Peter 2018 (2016): Wrights & Wrongs. My Life in Dance. Published in paperback with revisions. Oberon Books

NEWSPAPERS REVIEWS AND OTHER MATERIAL

Programme booklet, Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet 1949

The Stage, 30 May 1946: Sadler’s Wells ‘Khadra’

The Stage, 29 September 1949: Sadler’s Wells ‘Sea Change’

Richard Buckle, 2 October 1949, Observer: Ballet

Benoit Négrier, 10 November 2019. l’Éveil, Normand: Un denier hommage à la danseuse étoile Sheilah O’Reilly

Lauren Sanderson, 27 February 2017, Danz Dance Aotearoa New Zealand: Sea Change – The Wet Hot Beauties 21 February 2017, Parnell Baths, Auckland, Auckland Fringe https://danz.nz/sea

ONLINE:

Frederick Ashton: http://www.frederickashton.org.uk/shalott.html

Celia Franca Foundation: https://www.celiafrancafoundation.com

Honor Frost Foundation: https://honorfrostfoundation.org

Stuttgart Ballet: https://www.stuttgart-ballet.de/company/the-cranko-era/

John Cranko Gesellschaft e.V. : https.// www.johncrankogesellschaft.de/john-cranko.html

Royal Opera House: http://www.roh.uk/people/john-cranko

American Ballet Theatre: https//www.abt.org/ballet/sea-change

Danz Dance Aotearoa New Zealand: https://danz.nz/sea

Lauren Martyn: https://movementdanceeducation.com/about-lauren-martyn/timeline/

Het Nederlands Ballet: http.//teaterencyclopedie.nl/wiki/Het_Nederlands_Ballet

Foundation Serge Lifar: www.sergelifar.org

WIKIPEDIA articles

Frederick Ashton, Nadia Benois, David Bintley, Benjamin Britten, Richard Buckle, William Chappell, John Cranko, Celia Franca, Cyril Frankel, George Gé, Reginald Goodall, Walter Gore, Sol Hurok, Constant Lambert, John Lanchbery, Lauren Martyn, John Piper, Joanna Priest, Elsa Sylvestersson, John Millington Synge, Antony Tudor, Jorma Uotinen, Ninette de Valois, Guy Warrack, Peter Wright, Sea change (idiom), Aldeburgh Festival, Cassis (France), Gaiety Theatre (Irland), Het Nationale Ballet, Sadler’s Wells Theatre, Theatre Royal Hanley

FOOTNOTES

[1] I would like to thank professor Karl Toepfer for his support and inspiring thoughts while writing this article.

[2] Clarke 1955, pp. 311–315