Jean Sibelius:

String Quartets in E flat major, A minor, B flat major and D minor ‘Voces intimae’

Breitkopf & Härtel Jean Sibelius Werke SON 634

Edited by Pekka Helasvuo and Tuija Wicklund

Some years ago it was widely believed that Sibelius wrote only one string quartet – Voces intimae – a work that remained a relative rarity on international concert programmes, although it was held in high regard by connoisseurs of the genre. In 1931 Cecil Gray wrote that it ‘ranks with the finest achievements of Sibelius’s middle period […] beautifully written for the medium and exceedingly effective in performance’.[1] Fast forward to the present day: thanks primarily to the Sibelius’s family’s donation of manuscripts to the National Library of Finland in 1982 and the pioneering research of Kari Kilpeläinen, Fabian Dahlström and many others, our knowledge of the range and extent of Sibelius’s output is now considerably more complete. In fact he completed four string quartets plus a number of individual movements. The four completed works are contained in this new volume of the JSW Critical Edition.

The earliest and shortest of the four is the String Quartet in E flat major (JS 184), composed in Hämeenlinna just before Sibelius set off for his studies in Helsinki, although we know of no performances during the composer’s lifetime. We may well agree with Karl Ekman, who in 1935 was the first to evaluate the work: ‘This last composition from his school years reveals a technical ability and handling of form, striking for a novice in music, who has had no other teacher than himself’[2]. The influence of Haydn is evident, especially in the first movement. The two central movements are quite short. If the character of the slow movement is hard to define (the many melodic and textural demisemiquavers in apparent contradiction to the Andante molto marking), the scherzo and Vivace finale are refreshingly down-to-earth.

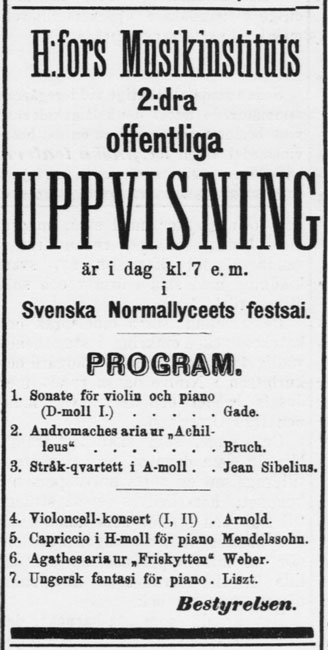

Next is the String Quartet in A minor (JS 183) from 1889, his final year of study under Martin Wegelius in Helsinki. The work was premiered at a concert at the Helsinki Music Institute on 29 May of that year and was positively reviewed in the press. Of all Sibelius’s string quartets, this comes closest to the melodic abundance of his finest pieces for piano trio from the second half of the 1880s – the ‘Hafträsk’, ‘Korpo’ and ‘Lovisa’ Trios. Its Adagio ma non tanto slow movement, which drew praise at the premiere (‘Here one is immediately captivated by the inherent poetry and beauty of the motifs; the impression of the entire movement is magnificent’[3]), shares its gently swaying 9/8-metre and its key of E major with the corresponding movement of the ‘Hafträsk’ trio. Whereas the trio movement is a fresh and spontaneous barcarole, however – one can imagine Sibelius writing it down just after taking a boat trip in Hafträsk bay – its quartet counterpart views the voyage from a respectful distance, as if describing the same event in polite company many months later.

Among Sibelius’s independent movements for string quartet is one that is generally known as Fugue for Martin Wegelius [JS 85]; according to research by Kari Kilpeläinen[4], this was probably originally envisaged as the finale of the A minor Quartet. The Fugue is not included in this volume of JSW.

Newspaper advert in ‘Finland’, 29 May 1889, promoting the premiere of the String Quartet in A minor

The String Quartet in B flat major, completed in 1890 a few months after the Piano Quintet in G minor [1890; JS 159], was the only one of these three early works to receive several performances during the composer’s lifetime, though not all of them were complete. It is also the only one of the three that would ultimately bear an opus number – Op. 4 (a number that Sibelius had also considered giving to various other works including the Piano Quintet and Suite in A major for string trio [1889; JS 186]). It is similar in proportions to the A minor Quartet but more serious in tone throughout. Here too, an ostensibly independent movement may have been intended for the quartet, in this case the very beautiful Adagio in D minor, JS 12, which may have been a first attempt at the slow movement (it is not included in the present volume).

A trend towards greater earnestness (and indeed larger instrumental forces) is discernible in Sibelius’s chamber music as he prepared to take the decisive leap towards orchestral music. Indeed the quartet’s scherzo, Presto, bridges the gap between chamber and orchestra music: it is often heard separately in Sibelius’s own transcription for string orchestra, made for a performance in Turku in early 1894. But whereas the thematic material of the Piano Quintet is conceived on a grand, almost epic scale, that of the B flat major Quartet is more intimate; and the harder Sibelius works with his motifs, the more strained they sound. In the slow movement, for instance, the expressive and rather beautiful main theme is drawn into a nightmarish realm where it is overwhelmed by the busy textures (bars 87–123). Overall this is not an easy piece to perform convincingly: passages such as the rising and falling dotted rhythms in the first movement (first heard in bars 23–24 ) or long stretches of the scherzo can easily sound mechanical if played with insufficient subtlety.

The JSW edition includes an incomplete early version of the first movement, here published for the first time. It runs to 232 bars, breaking off at the start of the recapitulation. From this it is clear that Sibelius had originally envisaged including an exposition repeat that he deleted from the final version; but there are many other significant differences from the final version throughout.

Whereas the first three quartets did not appear in print until decades after Sibelius’s death (Edition Fazer), the five-movement String Quartet in D minor ‘Voces intimae’, Op. 56, was published during his lifetime – by Lienau in 1909. It was around that time that Sibelius’s music started to assume a dark, uncompromising, often introspective character. When working on the quartet, he had already started to sketch ideas that he would use as incidental music for Mikael Lybeck’s symbolist play Ödlan (The Lizard), scored for a small string chamber ensemble. That intense score with its anguished, often nightmarish atmosphere clearly indicates the path that Sibelius was to follow both in Voces intimae and in other masterpieces over the coming years, culminating in the Fourth Symphony of 1911. As Sibelius himself remarked in a radio interview in 1948, Voces intimae was to a significant extent composed in London. Sibelius arrived there in February 1909, conducting his own music with great success and meeting various members of the British aristocracy, though he was living in fear of a recurrence of the tumour had been removed from his throat the previous year, and was thus forced to abstain from alcohol and cigars. The JSW introduction mentions a performance in early 1910 by the Alexander Mogilevsky’s Moscow Quartet in Russia (whether private or public is unknown), which predates what was previously believed to be the premiere in Helsinki on 25 April.

Numerous facsimile pages illustrate this handsome volume, including the original ending of ‘Voces intimae’ from the autograph score and an extra proposal for the very end of the piece (the ending did not reach its definitive form until late in the publication process, after proofs had been delivered). The extensive introductory essay places each work within the context of Sibelius’s life and career as well as discussing their origins and reception, and there are extensive critical annotations and commentaries.

Review by Andrew Barnett & Ian Maxwell

Review copy kindly supplied by Breitkopf & Härtel

Price: €326.00

328 pages – ISMN: 979-0-004-80369-1

Order link and more information: https://www.breitkopf.com/work/6198/18149

[1] Cecil Gray, ‘Sibelius’, Oxford University Press 1931, pp. 125–126

[2] Karl Ekman, ‘Jean Sibelius’, Otava 1935, p. 39. ‘Denna skolårens sista komposition röjde ett tekniskt kunnande och en behärskning av formen, påfallende hos en musikens adept, som icke haft någon annan lärare än sig själv.’

[3] Unsigned review in Finland, 31 May 1889: ‘Här fängslas man genast af den inneboende poesin och skönheten i motiverna; intrycket af hela denna sats är storslaget.’

[4] Kari Kilpeläinen, introduction to ‘Fugue for Martin Wegelius’, Edition Fazer, Helsinki 1994; also ‘The Jean Sibelius Musical Manuscripts at Helsinki University Library – A Complete Catalogue’, Breitkopf & Härtel 1991, p. 117