Click here to download this article as a pdf file

Valse triste revisited

De Basil’s Ballet Russe’s Sibelius in South America

Eija Kurki

It is not generally known that Jean Sibelius’s Valse triste has been performed on stage by Wassily de Basil’s Ballet Russe on the company’s tours in Brazil and in a revised version of the choreography in Barcelona in the late 1940s. In this article I shall discuss these performances and the people behind the two productions. Both of them were choreographed by Russian-born Nina Verchinina (1912–95) who also danced the leading role. Her choreography was premièred in São Paulo, Brazil, in 1946 and performed after that also in Rio de Janeiro. Brazil was the last country of De Basil’s Ballet Russe’s four-year-tour in Latin America. Verchinina revised her choreography for Barcelona in 1948; that was the last year that the company still performed on tours with de Basil, and it was disbanded a few years later.[1]

Colonel de Basil’s Ballet Russe

Serge Diaghilev’s famous company Ballets Russes came to an end in 1929. Three years later the Frenchman René Blum (1878–1942), director of the Monte Carlo Theatre, and the Russian Wassily de Basil (Colonel de Basil; 1888–1951) together established a company, Les Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, to continue the traditions of the Ballets Russes de Serge Diaghilev. The majority of the works performed had previously been staged by Diaghilev’s company, but other new works were commissioned. Its choreographers and dancers, such as George Balanchine, Leonid Massine, Michel Fokine and Bronislava Nijinska, had worked with Diaghilev’s company. Featured dancers included David Lichine, Leon Woizikowsky, Marian Ladré, Lara Obidenna and young dancers such as Irina Baronova (1919–2008), Tamara Toumanova (1919–96) and Tatiana Riabouchinska (1917–2000), all 13–15 years of age. After the immediate success of these girls, English writer Arnold Haskell (later headmaster of the Royal Ballet School) dubbed them the ‘baby ballerinas’ , and they were to become pillars of the company.[2]

Later the company was split in two: one was René Blum’s Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo while the other, De Basil’s company, performed under different names, as Col. W. de Basil’s Ballet Russe, Covent Garden Russian Ballet and finally, from 1939 on, with the name Original Ballet Russe. During these years choreographers and dancers swapped from one company to another. De Basil had even a second company which toured in Australia and New Zealand in 1936–37 while the first company performed in Europe, the United States and Canada. During World War II de Basil’s Original Ballet Russe left Europe and performed in the United States (as did Blum’s company).

From 1941 to 1946 de Basil’s company, the Original Ballet Russe, toured Latin America, and even had its headquarters in Argentina, at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. Later in 1946 the company performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York and toured in the United States. Back in Europe the following year, the company performed in London, Paris and Brussels. After a few months’ break, in the spring of 1948, it started touring in Spain, Portugal and Spanish Morocco, beginning in Barcelona. The last stop on the tour was Mallorca; these were the company’s last performances.

Valse triste in Brazil: São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro

In early 1946 the company toured Mexico, moving on to Havana, Cuba, and Rio de Janeiro in June/July, before arriving in São Paulo. The première of the choreography by Nina Verchinina of Sibelius’s Valse triste was at the Theatro Municipal in São Paulo on 26 July. Russian-born Nina Verchinina had studied both classical dance in Paris with Olga Preobrajenskaya and modern dance with Isadora Duncan. She had joined Les Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo in 1932 and created roles in Leonid Massine’s symphonic ballets in the 1930s, and was therefore known as ‘Ballerina Symphonica’ . She belonged to the inner circle of the company as her sister, dancer Olga Morosova was married to de Basil.

Vicente García-Márquez writes in his book The Ballets Russes that Valse triste was not based on any regional or folk tale, like the other ballets created during the tour in different countries: ‘but instead was a choreographic poem to melancholy: though man strives to achieve happiness, his soul is always overcome with sadness… Valse triste was an amplification of Verchinina’s personal choreographic vocabulary already explored in Quest, blending classical ballet with modern dance.’[3] Unfortunately Kathrine Sorley Walker does not mention this Valse triste in Brazil in her book about de Basil’s Ballets Russes (1982).

Verchinina’s Quest, previously named Étude, was premièred in Sydney during the company’s tour in Australia in 1940, with music by Bach. The all-female cast wore mauve, buff and blue leotards; there was no decor. Sorley Walker writes: ‘the choreography was based on her own fluent and forceful dance style’.[4]

In Valse triste there were two main female roles, Melancholy and Life, and a group of dancers. Verchinina danced the leading role of Melancholy and April Olrich from England took the role of Life. Olrich was de Basil’s last ‘baby ballerina’; she had joined the company during its tour in Chile in 1944 at the age of thirteen and was fifteen when she performed the role of Life.[5]

The scenery and costumes were designed by Jan Zach, a Czech residing in Brazil. [6] Jan Zach was later known mainly for his sculptural work. But how did this Czech artist come to join the team? The connection might be the Czech choreographer and dancer Ivan Psota (1908–52), who worked with the company during its Latin American tour.

In his article ‘Imagery, Light and Motion in My Sculptures’ (1970), Zach has described various phases of his work in Brazil, Canada and the United States. He writes about the time in Brazil: ‘I became very conscious of the tremendous impact of sunlight and of shadows. I observed that the shadows projected by a group of trees created a four-dimensional visual experience. This experience came to dominate my outlook as a sculptor. ’ Unfortunately, however, in the article there is only a mention of him making sets and costumes for Valse triste – nothing about the production and no description of his sets and costumes for the piece. [7] [8]

The orchestra of the opera house, Theatro Municipal, was conducted by William McDermott who had joined de Basil’s Ballets Russes in March 1943 in Lima, Peru at the time of the Latin American tours.[9] [10]

For her book Kathrine Sorley Walker interviewed McDermott, who told her about the precarious circumstances in which music was performed during the tour in rural areas, outside of the main cities. She describes his joining the company: ‘McDermott was a man with right humorous approach and adaptability for the extraordinary itinerant months that were to follow.’[11]

After São Paulo the company returned to Rio de Janeiro in August where Valse triste was performed at the opera house, Theatro Municipal.[12] Both opulent opera buildings where Valse triste was performed, the Theatro Municipal in São Paulo (1911) and Rio de Janeiro (1909), were inspired by the Paris Opéra of Charles Garnier.

Photo: PortoBay Hotels & Resorts. CC BY-ND 2.0 Deed (background edited)

After the tour in Brazil

After these performances in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro the company headed for New York where they performed at the Metropolitan Opera House followed by a tour in the United States. After this, back in Europe (performances in London, Paris and Brussels) de Basil’s Ballet Russe started a Spanish tour in Barcelona in 1948.

Valse triste’s choreographer and dancer of the role of Melancholy, Nina Verchinina did not travel to New York with the company. She stayed in Brazil, married the local Count Jean de Beausacq (who had represented the ballet company during the tour in that country), and took a position as choreographer and ballet maîtresse of the ballet company at the Escola de Dança at the Theatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro.[13]

Thus the choreographer and main dancer of Valse triste did not accompany the company to the United States, and this is probably the reason why Valse triste was not performed in the Metropolitan Opera and at the following performances in the United States and Europe. This is unfortunate, as Sibelius was popular and his music was played often in the United States and England in the 1940s, and therefore much of the audience could have been also familiar with his Valse triste.

Six years later, after the Valse triste performances in Brazil, another ballet company, ‘Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas’ , toured in both of these cities in 1952 (they had previously toured there in 1948). Some of the dancers of the company were from the former de Basil’s Ballet Russe, such as American Rosella Hightower, who had danced with the company during the tour in the United States. Also conductor William McDermott had joined the de Cuevas Ballet and again conducted opera orchestras in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. This time, when de Cuevas Ballet’s repertoire included Sibelius’s ballet pantomime Scaramouche, choreographed as a ballet by Hightower, the composer was already known to the local ballet audience. After touring in Brazil, de Cuevas Ballet performed Scaramouche the same year at the Edinburgh Festival with William McDermott conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.[14]

Valse triste in Barcelona

When de Basil’s company started touring in Spain Valse triste was performed in Barcelona, which was the first city on the tour. Nina Verchinina’s renewed Valse triste, with subtitle Elegía Coreográfica, was performed on 13 May at the Gran Teatro del Liceo. It was announced as first performance in Spain (estreno en España) and was repeated on 15 and 16 May, the latter being the last performance of the company in Barcelona.[15]

Verchinina had joined the company again for its European and Spanish tour. She had arrived in Europe with a few dancers from Brazil, the dance group of Nina Verchinina, backed by her husband, Count Jean de Beausacq. Her group had given some independent performances, but she now appeared regularly with de Basil’s Ballet. Her husband worked at the company too, as ‘Assistant to the Director’.[16]

Verchinina danced Melancolía (Melancholy) again, and Vida (Life) was Sandra Dieken, a Brazilian dancer from her own dance group who had now also joined de Basil’s Ballet Russe. There was also an ensemble named ‘Sombras’ (Shadows). A synopsis of the ballet is given in the programme book: ‘A deserted garden, surrounded by the ruins of a castle. Melancholy nurses mystery and desolation. The shadows flutter in a sombre atmosphere. A ray of light penetrates the darkness with the promise of new life. Turning to a joyous whirlwind, it struggles against the powers of darkness, but Melancholy releases her dark powers and finally defeats Life in her kingdom of the shadows.’[17] In Verchinina’s Valse triste, Melancholy conquers Life.

Las Sombras, the nine ‘Shadows’ , both male and female and under the command of Melancholy, were Jeanne Artois, Helene Voronova, Olga Barneva, Marita Kern, June Newstead, Betty Scott, Paul Grinwis, Kenneth Laurence and Guy Stambaugh. [18] Looking at the background of the dancers we observe that they were of different nationalities – Russian, English, American and Dutch – which shows how the company was put together for this tour. [19]

The scenery and costumes were by Manuel Muntañola. The archive at the Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques (digitalized archive of MAE) contain only drawings from 1948–49 for a Valse triste production made by Rafael Richart (1922–92), not the ones by Manuel Muntañola. The titles of the roles in the drawings are, however, the same as in Verchinina’s choreography: Vida (Life) and Melancolia (Melancholy). There is also Hombre (A Man, who is not mentioned in a list of characters in the 1948 programme) and a drawing of the scenery. The costumes were influenced by ancient Greece. Vida has a light pink dress, without sleeves and leaving one of her legs bare, and Greek-style shoes. Melancholy has a light blue-green dress with long sleeves stretching to the ankles and a long violet scarf covering her hair. The Hombre has a short light blue costume barely covering his hips, and one shoulder is bare.

In the scenery sketch there is a light brown desert; the horizon is far away, the sky grey-blue and pink. There are three Greek-style white pillars, all damaged; one is still standing, two others are about to fall. There is violet tissue like muslin, from a curtain, which binds them together. There is also light green-blue tissue that lies on the ground like a serpent. The scenery is reminiscent of Salvador Dali’s paintings.[20]

Verchinina toured with her dance group in Spain the following year, 1949, and it may be that these costumes and scenery were used at those performances.

Sibelius’s music was conducted by Walter Ducloux with the Orquestra de Gran Teatro del Liceu. The Swiss-born American Ducloux had joined the company for this European tour and had worked previously with Arturo Toscanini. The programme included, in order of appearance: Carnaval (Schumann-Fokine), Symphonie fantastique (Berlioz-Massine), Valse triste (Sibelius-Verchinina) and Graduation Ball (El Baile de los Cadetes; J. Strauss-Lichine). After each ballet there was an intermission. [21]

The company’s opening performance in Barcelona had been already on 20 April, however. García-Márquez writes: ‘When the company opened, after twelve-year absence from Barcelona, at the Teatre Liceu (April 20, 1948), it was welcomed ecstatically.’[22]

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

The Company’s Last Tour with de Basil

After Barcelona, there was an extensive tour of the Iberian peninsula and Spanish Morocco that ended six months later, in the beginning of November, on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca. During the tour the audiences were warm and enthusiastic; nobody suspected that this would be the last tour by de Basil’s Ballet Russe, marking the abrupt end of the company’s sixteen-year existence.[23]

A young dancer, the American Robert Barnett (b. 1925), later a dancer with the New York City Ballet and director of the Atlanta Civic Ballet, was on this tour. In his recently published memoir he tells about this tour, its financial difficulties, problematic accommodation and hazardous performing halls. The company had to bring hammers with them, as visiting opera companies had left nails on the stage floors.[24]

In different sources there are different listings of the cities visited during the tour. The most comprehensive is in Robert Barnett’s book. According to his itinerary, after Barcelona the company headed to the North-West, to the Basque area, then to Portugal and via Madrid south to Andalucia and Morocco. The last city on the Iberian peninsula was Valencia on the east coast, and then came the island of Mallorca. The tour visited Barcelona, Zaragoza, Pamplona, San Sebastián, Bilbao, Santander, Burgos, Valladolid, Salamanca, Porto, Lisbon, Madrid, Córdoba, Granada, Málaga, Tangier, Tetuán, Valencia and Mallorca.[25]

After de Basil’s Ballet Russe was disbanded, its dancers scattered all over the world. Many of its dancers founded various ballet schools and companies in Australia, many places in the United States, Canada and Latin America (Argentina, Peru, Cuba and Brazil), as was the case of Nina Verchinina. Of its ’baby ballerinas’ , Irina Baronova taught at the Royal Ballet School in London and Tatiana Riabouchinska opened a school with David Lichine in Beverly Hills, and directed several performing groups including the first Los Angeles Ballet.[26]

Kathrine Sorley Walker characterises Nina Verchinina, Valse triste’s choreographer, as follows: ‘Verchinina’s career can be clearly seen now as a bridge between old and new, classical and modern. She was a true innovator – an able, classically trained dancer who could understand and interpret moods and movements far beyond the normal range of ballet at the time.’[27]

It should be noticed that, unlike other Valse triste ballets, Verchinina did not stage it as a solo or as a male-female (Death-Maiden) duet. [28] She developed a female-female duet with a small ensemble of dancers. Unfortunately I have not been able to find any photographs of her Valse triste production in Brazil and Spain so far.

Marionettes and other Valse tristes

Before de Basil’s Ballet Russe’s Valse triste, there had been a performance in Spain by the ballet dancer Mariá de Ávila (1920–2014), who had choreographed and danced Valse triste as a solo in 1945. Her Valse triste with designs by Ginette Simont was performed at the Teatro Español in Madrid where there was a dance evening, ’Concierto de danza’ , by de Ávila and Joan Magriñà (1903–95), both at the time principal dancers of the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona. The evening was a collection of short dance performances and orchestral intermezzos. The orchestra of the theatre was conducted by Gerardo Gombau.[29]

Two years later, however, when the same duo had a dance performance in Barcelona at the Palau de la Música Catalana, Sibelius’s Valse triste was used as an intermezzo, played by the orchestra.[30]

After Valse triste by Ballet Russe at the Gran Teatre del Liceu in 1948, Sibelius’s music would later return to this significant theatre. To mark the Sibelius centenary, Joan Magriñà made a choreography named Evocación, for which Manuel Muntañola made the sets and costumes. It was labelled ‘Ballet in one act to the music by Sibelius’ , but so far there is no information about what music was used.[31]

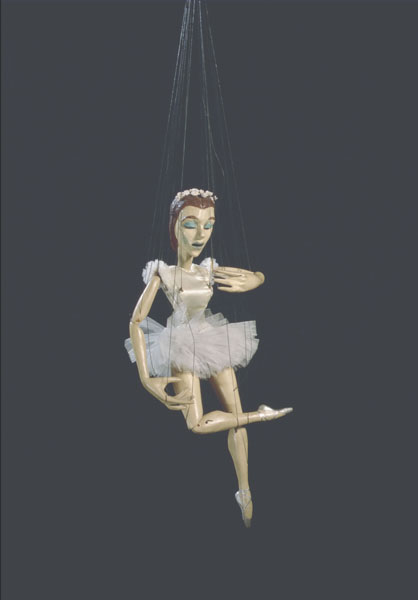

In Barcelona Sibelius’s Valse triste was also used at a marionette performance, El seu darrer bal (Her Last Dance) which was created by Harry Vernon Tozer in the late 1940s. The collection of his numerous marionettes is kept at the Centre de Documentació i Museu de las Arts Escèniques in Barcelona. They include his figures for Valse triste: the Classical Dancer, the Skeleton (Death) and the Crucifix, which can be seen online in the digitalized archive of MAE.[32]

Valse triste and de Basil’s Ballet Russe

Besides Nina Verchinina there were other dancers and choreographers involved with de Basil’s Ballet Russe who had a connection with Sibelius’s music.

George Balanchine (1904–83), the company’s first choreographer in 1932, later founder of the New York City Ballet, choreographed Valse triste in 1923 with his group Young Ballet in Sestroretsk, near Petrograd (today St Petersburg) for Lydia Ivanova. A critic remarked on the work’s ‘Duncanesque rhythmic plasticity’ . It was performed again in 1924 when Balanchine’s group visited Germany and London, danced by Tamara Geva (Balanchine’s wife) and Alexandra Danilova (future wife).[33] Balanchine, Geva and Danilova remained in Europe and joined Diaghilev’s company. Millicent Hudson and Kenneth Archer, a dance and design team based in London, made a reconstruction of it which was performed at the Finnish National Ballet in Helsinki in 2004 at the Balanchine Centenary Gala by the Finnish dancer Anna Sariola.[34]

Russian-born dancer Boris Kniaseff (1900–87), who made two choreographies for de Basil’s company that were premièred at London’s Covent Garden in 1947 (Piccoli and The Silver Birch, choreographies revived from Paris, Théâtre Marigny, 1940), choreographed Valse triste with the name ’Obsession’ in 1925. It was performed by his own company, ’Les Ballets Russes de Boris Kniaseff’ , at the Théâtre de l’Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and later with his company in Monte Carlo in 1931, at the invitation of René Blum, director of the Monte Carlo Theatre. Many of Kniaseff’s dancers eventually performed with Blum’s and de Basil’s Ballets Russe and Kniaseff himself danced at the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo in 1934.[35]

In Havana in 1946, the Cuban dancer and choreographer Alberto Alonso (1917–2013) made the choreography Sombras (The Shadows) to Sibelius’s First Symphony for the Escuela de Ballet.[36] Alonso had come into contact with de Basil’s Ballets Russe during its first tour to Cuba in 1936. He then danced and toured with his Canadian wife Alexandra Denisova (real name Patricia Denise; the names were ‘Russianized’ for publicity reasons) with the company from 1936 until 1941. He returned to Cuba to take a post as manager of Escuela de Ballet de la Socieded Pro-Arte Musica, for which he also made choreographies. During the years 1944–45 he danced with the New York Ballet. Sombras was also performed later by Ballet Alicia Alonso (his sister-in-law’s company), for instance in Buenos Aires, Argentina.[37] Ballet Alicia Alonso is now the National Ballet of Cuba.

In 1948 there had been a plan to film the whole repertoire of de Basil’s Ballet Russe during the tour to the Iberian peninsula and Morocco. The father of one of the young ballerinas, Barbara Lloyd, from the United States, had brought the equipment with him. Unfortunately there was a dispute between de Basil and David Lichine, a choreographer who not only danced in the company but was also a ballet master. So the plan fell through.[38] It is extremely unfortunate that this came to nothing, otherwise a film of the de Basil’s Original Ballet Russe’s Valse triste would probably exist.

NINA VERCHININA choreographer and in the role of Melancholy

The choreographer and dancer Nina Verchinina (1912–95) was born in Russia but raised in Shanghai. Some sources state that she was born as early as 1903. (De Wikidanca/Verchinina) After the Russian revolution in 1917, her family moved to Paris, where she studied classical dance with Olga Preobrajenskaya and Bronislava Nijinska, and modern dance with Isadora Duncan. From 1929 she danced in a company run by Ida Rubinstein. She joined de Basil’s and René Blum’s Les Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo in 1932. She created roles in Les Présages to Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony (1933, Monte Carlo), Choreartium to Brahms’s Fourth Symphony (1933, London) and Symphonie Fantastique to Berlioz’s music of the same name (1936, London), all with choreographies by Leonid Massine.

While de Basil’s Ballet Russe was on tour in Mexico and Havana, Cuba in 1941 she decided to stay there while the company headed for a tour to the United States and Canada. She stayed in Cuba for three years and danced with the Opera Ballet in Havana (Balé da Opera de Havana). She also took part in de Basil’s Ballet Russe’s first (1942) and third (1946) tours in Brazil. In the late 1940s Verchinina had a company of her own, Groupe de danses Nina Verchinina, which performed in Europe, and had a tour in Spain in 1949. She returned to South America in 1950s, first to Argentina, and in 1954 she arrived in Brazil, working as a choreographer for the Theatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro. She gave up choreography and devoted herself to teaching and was a major influence in the development of modern dance in Brazil.

APRIL OLRICH in the role of Life in São Paulo

April Olrich (1931–2014), who danced the role of Life, was an English ballerina. She was born in Zanzibar, where her father was a British diplomat, and she also lived in the Seychelles and Uruguay while she was growing up. She trained as a ballerina in Buenos Aires at the Teatro Colón under Michel Borovsky. April Olrich joined de Basil’s Ballet Russe during its tour in Chile in 1944 at the age of thirteen – de Basil’s last ’baby ballerina’ . Like the earlier ’babies’ she was accompanied by her mother.[39] She performed the role of Good in Cain and Abel, choreographed by David Lichine (Mexico City, 1946). After the tour in Latin America she joined the company’s tour to the New York Metropolitan Opera and tours in the United States as well as in the Europe.[40]

When De Basil’s Ballet Russe arrived in London’s Covent Garden in the autumn of 1947, Olrich was talent-spotted by the founder of the Royal Ballet, Dame Ninette de Valois, and joined its world-famous corps de ballet in 1949. In a very short time she became a soloist, dancing principal roles with the company for four years. After her ballet career she remained on the London stage as a performer. She appeared in many films, and on British television in both dramatic and comedy roles. In 2000 she created an award given by the Royal Ballet School for talented students. The April Olrich Award for Dynamic Performance is awarded annually at the School’s Ninette de Valois Junior Choreographic Awards.

SANDRA DIEKEN in the role of Life in Barcelona

Sandra Dieken (1930–2019) was born in Rio de Janeiro. She started her dance lessons at the Anglo-American school and later studied classical dance at the dance school of Theatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro. She joined Nina Verchinina’s dance group in 1947, and participated with her on a European tour with de Basil’s Ballet Russe; after that she toured also with Verchinina’s group in Spain. She returned to Brazil in 1950 and joined Theatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro where she danced until 1967 as a soloist and prima ballerina. She was also a teacher, founding a dance school of her own, the ’Academia de Artes Sandra Dieken’, in 1954. She made choreographies and promoted dance on television programmes. She moved to Germany in 1970, where she worked with Radio Deutsche Welle until 1990. She was rewarded with many awards, for example in 1965 from the Brazilian government.[41]

JAN ZACH scenery and costumes in São Paulo

Jan Zach (1914–86) was born in Slaný, north-west of Prague. He was apprenticed to several well-known painters, but it was the work of the sculptor Zdeněk Pešánek that deeply affected him. Pešánek was a pioneer of lumio-kinetic sculptures. While Zach was in New York in 1938, decorating the Czech Pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair, the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia. Zach never returned. He spent the 1940s in Brazil, joining the international art scene in Rio de Janeiro. He had large exhibitions of his paintings and drawings in 1943 and 1948 in Brazil. The following year, after the Valse triste premiere, he married Canadian Judith Monk, moved to the rural interior of Brazil and turned to sculpture. From Brazil he moved to Victoria, British Columbia in 1951, where he established an art school. In 1958 he was hired to teach sculpture at the University of Oregon.[42] Images of his sculptures are available online, among them The Dancer.

MANUEL MUNTAÑOLA I TEY scenery and costumes in Barcelona

Manuel Muntañola i Tey (1913–92) who was responsible for the scenery and costumes in Barcelona, was one of the most influential designers of the post-war time. He designed sets and costumes for several theatre and ballet companies, as well as for ballets made by Joan Magriñà (1903–65), who choreographed more than 150 operas and a score of ballets for the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona, including works in classical, Spanish and contemporary styles. Manuel Muntañola also worked with the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas in the 1950s, working for example on sets and costumes for Le Lien, choreographed by Paul Goubé to César Franck’s Symphonic Variations, premiered in Cannes in 1955.

WILLIAM McDERMOTT conductor in São Paulo

There is very little information to be found concerning the Valse triste conductor William McDermott (1916–2017). Besides working with de Basil’s Ballet Russe in the 1940s and Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas in the 1950s, he also conducted performances by British dancers Alicia Markova (‘Russianized’ name, real name Lilian Alicia Marks, 1910–2004) and Anton Dolin (1904–83), as they worked together with de Basil’s Ballet Russe.

McDermott also made arrangements and arranged and conducted music by Richard Wagner in Cain and Abel to David Lichine’s libretto and choreography, which was premiered by de Basil’s Ballet Russe in Mexico City (April 1946). The music was from Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen.[43] He made many arrangements of classical ballet music which are published, e.g. Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker and Swan Lake as well as Delibes’s Coppelia. He made arrangements particularly of the pas de deux from the major 19th-century ballets. He arranged also Cesare Pugni’s Pas de Quatre – Ballet divertissement (1845) for Alicia Markova, Nina Stroganova (the Dane Rigmor Ström), Rosella Hightower and Olga Morosova in New York in 1946.[44] There is a recording of this arrangement played by the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Richard Bonynge (Fête Du Ballet, A Compendium of Ballet Rarities, Decca).

Later McDermott conducted as far away as in Japan. He lived to be a centenarian and passed away in Florida. William McDermott is a forgotten musician, as so many like him who have worked composing, arranging, conducting and performing with ballet and theatre companies. His unpublished memoir would be of great interest also to Sibelius scholars. While touring with de Basil’s Ballet Russe in Latin America, William McDermott also worked in Chile and Brazil as accompanist to violinist Henryk Szeryng in the years 1942–46.[45] Szeryng often visited Finland often from the 1950s onwards and played Sibelius’s Violin Concerto.

WALTER DUCLOUX conductor in Barcelona

The Swiss-born American conductor Walter Ducloux (1913–97) studied in Munich and Vienna; he worked with Felix Weingartner, Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini and followed Toscanini to the United States. He joined the US Army in 1942 and, having linguistic skills, he was assigned to General George Patton as aide-de-camp and interpreter during the invasion of Germany. After the war he resumed his conducting career in Czechoslovakia and was the first American conductor of the Czech National Opera. He left the country after a communist regime came to power and took the post as a conductor of the de Basil’s Ballet Russe’s tour in Europe in 1948. A year later he returned to the United States, conducting different orchestras including Toscanini’s NBC Symphony Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra. In 1953 he moved to Los Angeles as professor of opera at the University of Southern California and director of USC Opera Theater. He translated more than 25 operas into understandable and singable English (from Italian, French, Czech and German).[46]

HARRY VERNON TOZER marionettes

Harry Vernon Tozer Tozer (1902–92) was an Englishman, born in Paraguay when his father worked there as administrator for the railway. During his schooling in England, when he was ten years old, he discovered the characters of Punch and Judy. In 1925 he moved to Barcelona. He was also interested in the Catalan puppets ‘putxinel-li’ . He made his first puppet in 1934, created a large number of marionette characters, and started performing. From the 1950s onwards he travelled around Europe to present his work. Tozer used to say that his attraction to puppets came from his love of model trains and the written word. His fondness for handicrafts led him to the string puppet, and he published several articles on this subject, establishing his international reputation; he received numerous awards.

© Eija Kurki 2021

Sources

Archive material

Edinburgh Festival Archive

Archive material online

Le Centre de Documentació Museu de Les Arts Escèniques (MAE)

Dipòsit Digital de Documents de la UAB

Finnish National Library

Literature

Barnett, Robert – Crain, Cynthia 2019: On Stage at the Ballet. My Life as Dancer and Artistic Director. Robert Barnett with Cynthia Crain. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina

Blake, Jon 2012: Walter Ducloux, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/96826637/walter_ducloux

Buckle, Richard 1979: Diaghilev. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. London

Chaves J., Edgard de Brito 1971: Memórias e glórias de um teatro: sessenta anos de história do Teatro Municipal do Rio de Janeiro. Companhia Editôra Americana.

Chazin-Bennahum, Judith 2011: René Blum and the Ballet Russes. In Search of a Lost Life. Oxford University Press

Crisp, Clement 2005: ’Le Grand Ballet du Marquis se Cuevas’ in the Journal of the Society for Dance Research. Vol. 23 No. 1 (Summer 2005). Edinburgh University Press, pp. 1–17

Garafola, Lynn 1989: Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Oxford University Press

García-Márquez, Vicente 1990: The Ballets Russes. Colonel de Basil’s Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo 1932–1952.

Alfred A. Knopf. New York

Hull, Roger: Jan Zach (1914–1986), https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/zach_jan_1914_1986

Kurki, Eija 1997: Sibelius’s music for the Play Kuolema. Incidental music to the play by Arvid Järnefelt: original theatre version.

CD booklet sleeve notes, BIS-915. BIS Records, Åkersberga, Sweden, pp. 9–11

Kurki, Eija 1999: ‘Järnefeltin Kuolema-näytelmä ja Sibeliuksen Valse triste’ in Niin muuttuu mailma, Eskoni. Tulkintoja kansallisnäyttämöstä. Ed. Pirkko Koski. Helsinki University Press

Kurki, Eija 2001: ‘Sibelius and the theatre: a study of the incidental music for Symbolist plays’ .

In Sibelius Studies, ed. Timothy Jackson and Veijo Murtomäki. Cambridge University Press, pp. 76–94

Kurki, Eija 2020a: Scaramouche – Sibelius’s horror story. Sibelius One 01/2020, England. pp. 7–28, available also online at https://sibeliusone.com/music-for-the-theatre/scaramouche/

Kurki, Eija 2020b: A play about death, but the music lives on. Sibelius One 07/2020. England, pp. 14–21, available also online in https://sibeliusone.com/music-for-the-theatre/kuolema/

Marvia, Einari – Vainio, Matti 1993: Helsingin Kaupunginorkesteri 1882–1982. WSOY

Revista de estudios musicales 1949. El Departamento de Musicología. Universidad National de Cuyo

Roth, Henry 1997: Violin Virtuosos: From Paganini to the 21st Century. California Classic Books.

Sorley Walker, Kathrine 1982: De Basil’s Ballets Russes. Hutchinson. London-Melbourne-Sydney-Auckland-New York-Johannesburg

Windreich, Leland 1979: ‘The Career of Alexandra Denisova: Vancouver, de Basil, and Cuba’ . In Dance Chronicle,

Vol. 3 No. 1 (1979). Taylor & Francis Ltd

Zach, Jan 1970: ‘Imagery, Light and Motion in My Sculptures’ . In Leonardo, Vol 3. No. 3 (July 1970). Pergamon Press, pp. 285–293

Anonymous sources online

Encyclopedia and Wikipedia articles about the persons involved, where found.

Choreographers and dancers:

Nina Verchinina: De Wikidanca. http://www. wikidanca.net/wiki/index.php./Nina_Verchinina

April Olrich: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/April_Olrich

Sandra Dieken: São Paulo Companhia de Danca (SPCD): https://spcd.com.br/verbete/sandra-dieken/

Rosella Hightower: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosella_Hightower

Joan Magriñà: http://www.spanisculture.com/en/artistas_creadores/joan_magrina

The George Balanchine Foundation: http://www.balanchine.org

Hodson Archer – Ballets Old & New: http://hodsonarcher.com/Hodson_Archer_-_Ballets_Old_&…

Designers:

Manuel Muntañola i Tey. Centre de Documentació

Museu de les Arts Escèniques: http://www.institutdelteatre.cat/publications/ca/enciclopedia-arts

Conductors:

William McDermott: https://woollywesterneye.wordpress.com/2017/10/03/william-mcdermott

Others:

Harry Vernon Tozer: Viquipèdia. http://ca.wikipeida.org/wiki/Harry_Vernon_Tozer; World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts https.//wepa.unima.org/en/harry-vernon-tozer/

Eija Kurki (b. 1963) published her dissertation Satua, kuolemaa ja eksotiikkaa. Jean Sibeliuksen vuosisadan alun näyttämömusiikkiteokset (Fairy-tale, Death and Exoticism. Jean Sibelius’s Theatre Music from the Beginning of the 20th Century) in 1997 at the University of Helsinki and has subsequently continued her research, uncovering much previously unknown information about the plays, Sibelius’s fascinating scores and their performance history, writing numerous articles in various specialist publications both in Finland and internationally (e.g. Sibelius Studies, Cambridge University Press, 2001). She has written the booklet notes for several world première recordings of Sibelius’s music on the BIS label, texts that have won praise from leading Sibelians such as Robert Layton. In November 2024 she published, together with Professor Karl Toepfer from San Francisco, the most comprehensive study of Sibelius’s tragic pantomime Scaramouche, comprising 170 pages.

Since 2017 she has also been researching the Swedish-born theatre composer Einar Nilson (1881–1964), his life and work with director Max Reinhardt.

Footnotes

[1] I would like to thank professor Karl Toepfer for his support and inspiring thoughts while I was writing this article.

[2] Sorley Walker 1982, pp. 180–194, chapter The Baby Ballerinas; Garcia Marquez 1990, pp. 6–27

[3] García-Márquez 1990, p. 291

[4] Sorley Walker 1982, pp. 126, 129–130

[5] Sorley Walker 1982, pp. 126, 129–130

[6] García-Márquez 1990, pp. 290–291

[7] Zach 1970, p. 285

[8] Ivan Psota had previously danced with the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo in 1932–36 and now again joined the company during its four year Latin American tour as a choreographer. He made the choreographies Fue una vez (1942, Buenos Aires), El Malón (1943, Buenos Aires), La isla de los Ceibos (1944, Montevideo), YX-KJK (1945, Guatemala) and Yara (1946) in São Paolo with a Brazilian team (librettist, composer and designer all local artists) just a few days after the première of Verchinina’s Valse triste. (Sorley Walker 1982, p. 126; García-Márquez 1990, pp. 287–291)

[9] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 127; García-Márquez 1990, pp. 286, 290–291

[10] The Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo conductors from the beginning of the 1930s, the Russian Efrem Kurtz (1900–95) and the Hungarian Antal Doráti (1906–88) took positions in 1938 with the two divided companies: Kurtz remained with Blum’s company and Doráti with de Basil. Russian-born American conductor Alexander Smallens (1889–1972) replaced Doráti in 1941 during a tour in the United States, and the Russian Eugene Fuerst joined the company in Mexico City in 1942. (Sorley Walker 1982 pp. 113, 122–123, 302–303)

[11] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 127

[12] Chaves J. 1971, p. 288

[13] De Wikidanca/Verchinina

[14] Brazil 1952: Chaves J. 1971, p. 297; Edinburgh 1952: Programme leaflet. Rosella Hightower (1920–2008) had previously danced with Ballets Russes in 1938–41 with René Blum’s company and in 1946–47 with de Basil’s company during its tour in the United States; Kurki 2020a

[15] Programme books, 13, 15 and 16 May 1948

[16] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 149. During the following tour, a few months later, Verchinina also made a new choreography, Suite Choréographique to music by Gounod, premièred in Bilbao, 14 September. (Sorley Walker 1982, pp. 150, 272–273; García-Márquez 1990, p. 311

[17] ‘En el jardín abandonado cerca de las ruinas de un castillo, la Melancolía conserva siempre misiterio y desolación. Sombras flotan en una atmósfera abrumadora. Rasga las tinieblas un rayo de luz que anuncia una nueva Vida. Torbellino de alegría trata de combatir las fuerzas sombrías, pero la Melancolía desencadena su poder oculto y finalmente vence a la Vida haciéndola caer en el reino de las sombras.’ (Programme book, 13 May 1948) Sorley Walker writes erroneously that Melancholy is put to flight by the arrival of New Life, 1982, p. 150)

[18] Programme book, 13 May 1948

[19] See about the assembly of De Basil’s company for the tour in Sorley Walker 1982, pp. 148–151

[20] MAE

[21] Programme book, 13 May 1948

[22] García-Márquez 1990, p. 310. Valse triste was not performed on 20 April, as one might think from García-Márquez’s book. That was the date of the company’ first performance in Barcelona with the programme Sylphides (Chopin-Fokine), Paganini (Rachmaninov-Fokine) and Graduation Ball (J. Strauss-Lichine), the latter was the first performance in Spain. (Programme book, 20 April 1948) Sorley Walker states that Verchinina restaged Valse triste in Madrid in May, which is also incorrect, as it was in Barcelona in May. (Sorley Walker 1982, pp. 274–275)

[23] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 149; García-Márquez 1990, pp. 310–311

[24] Barnett-Crain 2019, pp. 46–61

[25] Barnett-Crain 2019, p. 55. Sorley Walker mentions visiting some 22 cities, but names only nine, including Seville (1982, pp. 149–151). García-Márquez mentions 13 cities, including three venues in Madrid, and performing in Barcelona and Bilbao twice: Barcelona (Gran Teatro de Liceo), Madrid (Zarzuela Theatre), Bilbao, San Sebastian, Madrid (Albeniz Theatre), Lisbon, Porto, Valencia, Madrid (Retiro Park), Bilbao, Santader, Salamanca, Málaga, Tangier, Tetuán, Barcelona (Tivoli Theatre) and, finally, Mallorca. He mentions not finding any documentation of visiting Seville and Granada, as is stated in Sorley Walker 1982. (García-Márquez 1990, pp. 310–311, 326) None of the writers have any documentation in the footnotes of these numbers and cities.

[26] García-Márquez 1990, p. 316

[27] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 225

[28] Kurki 2020b

[29] Programme, 12 March 1945, MA

[30] Programme, 2 March 1947, MAE. In the autumn of 1948 Joan Magriñà was among the prominent Spanish artists involved with de Basil’s new project, the creation of a National Academy to develop Spanish Ballet. (García-Márquez 1990, p. 311; 313).

[31] Poster, Gran Teatre del Liceo, performances 22–29 December 1964, MAE

[32] El seu darrer bal (Su último baile) ó El vals trist de Sibelius, de Harry Vernon Tozer. Número de varietats en sol acte de 1949; Bailarina clásica, Esqueleto (La Mort) and Crucifix. MAE

[33] The George Balanchine Foundation

[34] Photos available online, Hodson Archer Ballets Old & New

[35] Chazin-Bennahum 2011, pp. 90, 231; Sorley Walker 1982, pp. 147, 168–271; García-Márquez 1990, pp. 112, 306–308

[36] Windreich 1979

[37] Revista 1949, p. 241

[38] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 150

[39] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 128–129

[40] Sorley Walker 1982 p. 128–138. Walker interviewed Olrich for her book.

[41] Sandra Dieken, SPCD. São Paulo Companhia de Dança

[42] Hull

[43] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 134; García-Márquez 1990, p. 292

[44] Sorley Walker 1982, p. 140

[45] Roth 1997, p. 177

[46] Blake 2012