Click here to download this article as a pdf file

Scaramouche

Sibelius’s horror story

Eija Kurki

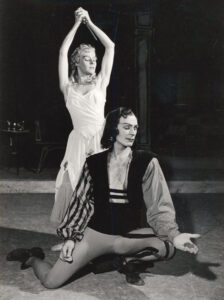

Klaus Salin as Scaramouche and Sorella Englund as Blondelaine in 1965

© Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara

Scaramouche. Ballet in 3 scenes; libr. Paul [!] Knudsen; mus. Sibelius; ch. Emilie Walbom. Prod. 12 May 1922, Royal Dan. B., Copenhagen. The b. tells of a demonic fiddler who seduces an aristocratic lady; afterwards she sees no alternative to killing him, but she is so haunted by his melody that she dances herself to death. Sibelius composed this, his only b. score, in 1913. Later versions by Lemanis in Riga (1936), R. Hightower for de Cuevas B. (1951), and Irja Koskkinen [!] in Helsinki (1955).

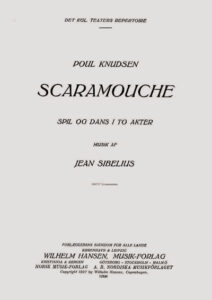

This is the description of Sibelius’s Scaramouche, Op. 71, in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Initially, however, Sibelius’s Scaramouche was not a ballet but a pantomime. It was completed in 1913, to a Danish text of the same name by Poul Knudsen, with the subtitle ‘Tragic Pantomime’. The title of the work refers to Italian theatre, to the commedia dell’arte Scaramuccia character. Although the title of the work is Scaramouche, its main character is the female dancing role Blondelaine.

After Scaramouche was completed, it was then more or less forgotten until it was published five years later, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922. Performances of Scaramouche have attracted little attention, and also Sibelius’s music has remained unknown. It did not become more widely known until the 1990s, when the first full-length recording of this remarkable composition – lasting more than an hour – appeared.

Previous research

There is very little previous research on Sibelius’s Scaramouche. Early Sibelius writers devote just a few sentences to the work and claim, essentially, that Sibelius would not have been interested in this composition.

In 1931, Cecil Gray wrote: ‘The music to Scaramouche, a tragic pantomime by Poul Knudsen, is also in fantastic vein. The scenario, based upon the hackneyed theme of the sinister stranger who lures away a wife from her husband, is unfortunately weak. In consequence, probably, the composer does not seem to be interested in his task as he certainly seems to be in Swanwhite. With all its technical brilliance and mastery one feels something rather mechanical and uninspired about it.’[1] Almost thirty years later, in 1959, Harold E. Johnson wrote: ‘One suspects that he found it difficult to work up any real enthusiasm for his task. It is, however, competently written, and it follows the stage action closely.’[2]

The Sibelius biographer Erik Tawaststjerna investigated the origins of the work by means of diary entries and correspondence, but did not provide any analysis of the composition. Erkki Salmenhaara described the work to some extent in his Sibelius book. More broadly, Scaramouche was discussed by Andrew Barnett in connection with the world première recording in 1990;[3] he also wrote about the relationship between Poul Knudsen’s text and Sibelius’s music, so in this article I will only look at the work in general terms. Barnett also examined Scaramouche in his Sibelius book published in 2007.[4] Barnett’s sleeve notes have been the source for other scholars, such as Marc Vignal and Jean-Luc Caron.[5] In her 2017 thesis Nordic Incidental Music, Leah Broad deals with Scaramouche as part of her research perspective, but not the work in its entirety, and among Scaramouche performances, she focuses on one in Stockholm in 1924. [6]

Although Scaramouche was completed in 1913, it was then forgotten until it was performed nine years later.[7] It was published five years after having been completed, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922 (see below). Projected venues were not only Royal Theatre in Copenhagen but also three Finnish theatres: the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki, the Finnish National Theatre and the Finnish Opera (Finnish National Opera). After the première in Copenhagen, the work was heard in no fewer than three other Nordic capitals within two years: Helsinki, Oslo and Stockholm. Karen Vedel, who has studied these performances, has shown in her article Scaramouche 1922–1924: Ballet pantomime in four Nordic Capitals (2014) that in real terms there were only two productions of Scaramouche, those in Copenhagen and Helsinki, as the Copenhagen version was also exported to Oslo and Stockholm.

Concerning theatre research, it is interesting that the Austrian researcher Heinz Kindermann mentions Scaramouche in Part IX of his ten-book series Theatergeschichte Europas (The History of Theatre in Europe; 1970).[8]

Scaramouche is related to the commedia dell’arte tradition, but among earlier writers only Barnett and then Vignal have pointed out this connection.[9] More recently Karen Vedel has also mentioned this link.[10] In his article Neo-classical Opera from 2005, Chris Walton mentions Scaramouche while discussing works associated with the commedia dell’arte (Ferruccio Busoni’s opera Arlecchino and Ernst von Dohnányi’s music for Schnitzler’s pantomime Der Schleier der Pierrette): ‘Another, roughly contemporaneous, “pantomime” using a character from the commedia dell’arte was Sibelius’s Scaramouche… again, its approach is far removed from Busoni’s, and it was in any case not performed until 1922.’[11]

In this article I shall first examine two related themes: the commedia dell’arte as a well-known theatrical form, and pantomime.

Scaramouche and the commedia dell’arte

The commedia dell’arte originated in Italy, from where it spread throughout Europe. Touring theatre companies performed it in public places such as markets. The heyday of this theatrical form ran from the early 16th century to the middle of the 18th century. Characteristics of the genre are the fixed characters of the actors and similar outlines for the plots and scenes, on the basis of which the actors improvised their performances. The characters were easily recognizable, wearing masks over their faces and costumes associated with the character in question. The cast consisted of a number of contrasts: rich / poor, old / young, master / servant. The characters were divided into three main groups: servants (i zanni), old people (i vecchi), and lovers (gl’innamorati).

Costume designs for grotesques and commedia dell’arte characters (1680)

by Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636–1707)

Among the male servants were Arlecchino (Harlequin), Brighella and Pulcinella. Pulcinella was humpbacked. The Pulcinella character was the role model for the Kasper puppet in Germany and Punch (Punchinello) in England. Pedrolino is a servant of the type that formed the model for the French character Pierrot. Female servants included both young women (such as Colombina) and old ones (such as La Ruffiana). There were various different names for young female and male lovers. Elderly characters include Pantalone (rich but senile), Il Dottore (a wise man) and Il Capitano (an army captain who boasts of his exploits). Scaramuccia (Scaramouche) is a variation of Il Capitano.

Scaramuccia was made famous by the actor Tiberio Fiorilli (1608–94). ‘He transformed the military role (Il Capitano) to that of a comic servant, usually an indigent gentleman’s valet. Scaramuccia is an unscrupulous and unreliable servant. His affinity for intrigue often landed him in difficult situations, yet he managed to extricate himself, usually leaving an innocent bystander as his victim.’[12]

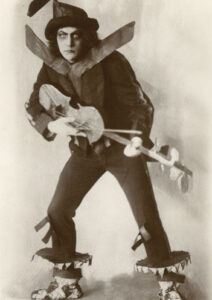

Tiberio Fiorilli as Scaramouche

(frontispiece from Angelo Constantini’s La Vie de Scaramouche, publ. 1695. Public domain)

In a break with tradition, Fiorilli performed without a mask. The essence of the character came from his own appearance: a large nose, a big moustache and whiskers. He wore black trousers, a jacket and a beret. In old drawings and paintings, the Scaramouche character is often depicted with a musical instrument – a guitar or violin.[13] Italian theatre companies took the commedia dell’arte to France and Scaramouche-Fiorilli acted with Molière. Molière worked with the composer Jean-Baptiste Lully and, for example, his play Le bourgeois gentilhomme (1670) includes a ‘Chaconne de Scaramouche’ written by Lully.

The commedia dell’arte was closely associated with dance, and the actors were multi-talented: actors, dancers, singers and acrobats. There is also a special dance step from this period called the ‘Pas de Scaramouche’, which was used by Tiberio Fiorilli and his successors. The commedia dell’arte dancer Barry Grantham describes this step as follows: ‘The performer slides into a forward split and pulls up onto the front leg. By repeating this on alternate legs he is able to cross the stage in a few moves. It requires considerable strength and is more for the acrobat than the dancer.’[14]

Ballet-pantomimes and Scaramouche

at the beginning of the 20th century

Pantomime is based on the gestures, expressions and movements of its performers and has a connection to the commedia dell’arte. In ballet-pantomime, developed at the Paris Opera in the mid-19th century, the pantomime includes dance as well. Pantomime and ballet-pantomime were popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

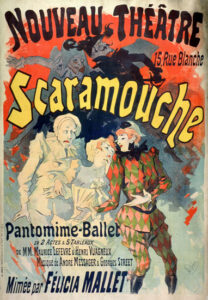

Commedia dell’arte characters made the transition to ballet-pantomime, and in Paris a ballet-pantomime named Scaramouche was performed at the Nouveau Théâtre in 1891, written by the Belgian Maurice Lefèvre with music composed by André Messager (1853–1929). Messager’s ballet-pantomime includes a scene entitled ‘Scène d’hypnotisme de Scaramouche’. This was revived as a ballet at the Grand Opéra in Avignon on 1 December 2019.

In France, Paul Verlaine had already shown an interest commedia dell’arte characters. His collection of poems Fêtes galantes (1869), contains several poems on the themes of commedia dell’arte characters and pantomime. These poems inspired music by Claude Debussy from the 1880s onwards (including Pantomime and Fantoches, featuring Scaramouche and Pulcinella).

In 1888 the pantomime Scaramouche in Naxos by the Scottish poet John Davidson (1857–1909) was published, in which Scaramouche is the impresario ‘A Showman’. [15] This is probably connected with Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s libretto for Richard Strauss’s opera Ariadne auf Naxos (1912–16).[16]

In his study Carnival, Comedy and the Commedia. A Case Study of the Mask of Scaramouche (1998), Stephen P. J. Knapper has explored the background and history of the Scaramouche character before the time of Fiorilli , the character as created by Fiorilli, and later appearances of the Scaramouche character. In this context, he also briefly mentions Sibelius’s Scaramouche: ‘Wicked too [like in André Messager’s ballet-pantomime] is the Scaramouche of a pantomime ballet performed in Copenhagen in 1922, with a score completed by Sibelius in December 1913. Scaramouche is here in his most grotesque incarnation, a black-robed, hunchbacked dwarf viola player whose music drives a noblewoman so wild that she kills him and then dances herself to death.’[17]

The commedia dell’arte interested artists of various disciplines in the early 20th century, such as Picasso in the visual arts and Schoenberg in music (Pierrot lunaire, 1912). These characters are also featured in Schumann’s piano work Carneval, an orchestrated version of which was performed in Paris in 1910 by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, who went on in the next few years to present Stravinsky’s commedia dell’arte ballets Petrushka (1911) and Pulcinella (1920). J. Douglas Clayton, who has studied the Russian commedia dell’arte tradition, describes Petrushka as belonging to the ‘Russified Pierrotic tradition’.[18]

The commedia dell’arte is also linked to neo-classicism in music, as is shown for example by Ferruccio Busoni’s operas Arlecchino and Turandot, which were premièred in Zürich in 1917. The figure of Scaramouche also appears in 20th-century works asociated with the commedia dell’arte, for example Richard Strauss’s opera Ariadne auf Naxos and in the ballet Les Millions d’Arlequin (music: Riccardo Drigo, 1900) with choreography by Marius Petipa.

Scaramouche films and other Scaramouches

The commedia dell’arte also found its way into a new art form: film. In 1913, the film Das Schwarze Los, written by Sibelius’s friend Adolf Paul, was completed in Germany; it also appeared under the title Pierrots letzte Abenteuer (Pierrot’s Last Adventure). In 1923, the popular silent film Scaramouche (Metro Pictures) was completed in the USA. It is based on Rafael Sabatini’s historical novel Scaramouche, published two years earlier, which tells the story of a young lawyer during the French Revolution. One of his adventures is to join a travelling commedia dell’arte company, playing the character of Scaramouche. The film was a success, and in 1924 it was shown in Finland too. The film critic of Hufvudstadsbladet warned: ‘[It] should not be confused with the love story for which Sibelius composed music.’[19] Sabatini’s novel was filmed again in 1952 (Metro-Goldwyn Mayer).

Darius Milhaud (1892–1974) composed a suite for two pianos named Scaramouche, which he later arranged for saxophone (or clarinet) and orchestra. The music had originally been composed for Moliérè’s play Le medécin volant (The Flying Doctor), which was performed in 1937 in Paris at the Théâtre Scaramouche, a theatre that concentrated on performances for children, and the name of Milhaud’s composition comes from there. In 2005 the ballet dancer José Carlos Martínez (b. 1969) devised choreography for this music for the École de Danse de l’Opéra National de Paris: the title was Scaramouche, and it also included ballet music by Tchaikovsky, Minkus and others.

The character of Scaramouche has also found his way into Punch and Judy performances and is featured in popular culture, such as the lyrics of the British group Queen’s song Bohemian Rhapsody (Freddie Mercury, 1975). This incarnation of Scaramouche is probably the one that is best-known today, as people who have heard this song can be counted in billions.[20]

The popularity of pantomine and ballet-pantomime

The popularity of pantomime and ballet-pantomime is linked to modernist thinking at the turn of the 19/20th centuries as a means of bodily expression. In his book Body ascendant. Modernism and the Physical Imperative Harold B. Segel has explored the appearance of dance and physical expression on stage in this period. In this context, he deals separately with works in which these are found, such as pantomimes.[21]

Another researcher, Hartmut Vollmer, examines pantomime with particular reference to German literature in his study Die literarische Pantomime. Studien zu einer Literaturgattung der Moderne (2011). Both researchers discuss works such as Arthur Schnitzler’s Der Schleier der Pierrette, but neither mentions Knudsen’s Scaramouche.

The Austrian writers Hugo von Hofmannsthal (Die Grüne Flöte [The Green Flute]), Richard Beer-Hofmann (Pierrot Hypnotiseur) and Arthur Schnitzler (Der Schleier der Pierrette) all wrote texts for pantomime and ballet-pantomime. As is already shown by the work titles, the latter two have links with commedia dell’arte. As with Messager’s ballet-pantomime, Beer-Hofmann’s text includes references to hypnotism, reflecting the turn-of-the-century fascination with this subject.[22]

Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s famous prose work Ein Brief (The Letter of Lord Chandos) from 1902 expressed his dissatisfaction with verbal expression and an interest in the non-verbal sort. [23] In 1911, the article Über die Pantomime (On Pantomime) was published, written by Hofmannsthal while he was collaborating with the famous dancer Grete Wiesenthal. [24] Both of these are central texts concerning pantomime in the early twentieth century. With his interest in pantomime and dance, Hofmannsthal also collaborated with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. In May 1914, Josephslegende (The Legend of Joseph), based on a libretto by Hofmannsthal and Harry Graf Kessler, was premièred in Paris. The music was by Richard Strauss, who also conducted the first performance. The next month the Ballets Russes performed it in London, where Strauss again conducted the music at the first night.[25]

Max Reinhardt (1873–1943), an Austrian director and theatre manager working in Berlin, was also interested in pantomime. The pantomimes he directed gained great popularity and were also performed in London, Paris and New York, such as the Oriental-themed Sumurûn (Friedrich Freksa / Victor Holländer, 1910) and the religious mystery play Das Mirakel (The Miracle; Karl Vollmoeller / Engelbert Humperdinck, 1911), the latter of which was premièred in London and performed hundreds of times on tour in the United States.[26]

As a result of the popularity of these pantomimes, Reinhardt wanted to establish a dance and ballet department in his theatre. He collaborated with dancers such as Grete Wiesenthal. It was probably the acclaim found by his own pantomimes, in conjunction with the success of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, that boosted Reinhardt’s interest in dance. [27]

In Oslo in 1915 Reinhardt had seen the 16-year-old Norwegian dancer Lillebil Christensen (1899–1989) ‘twirling’,[28] and secured her services in his theatre company.[29]

Sibelius, dance and pantomime

Overall, the dance genre was relatively insignificant in Finland in the early 20th century, with regard both to ballet and to modern so-called ‘free dance’. On his numerous trips abroad, Sibelius followed what was happening in the arts, including dance. The famous American pioneer of free dance Isadora Duncan (1877–1927) visited Helsinki in 1908, but Sibelius was already familiar with her work, having seen her in Berlin 1905, from where he wrote to his wife Aino: ‘Tonight, soon, I’m going to see Isadora Duncan, the dancer. [Adolf] Paul says it’s just humbug. Now we’ll see.’[30]

Before Scaramouche, Sibelius had composed a large amount of stage music that included both pantomime and dancing, as specified by the playwrights of the time. The best-known of the dances is from the music to Arvid Järnefelt’s play Kuolema (Death; 1903), from the pantomime and dance scene of which he extracted Valse triste. The two pieces he added for a revised version of the play were also composed for pantomime and dance scenes: Valse romantique and Canzonetta (1911). The incidental music to Hjalmar Procopé’s Belshazzar’s Feast (1906) features Khadra’s dances of life and death. August Strindberg’s Swanwhite is rich in pantomime scenes for which Sibelius composed several musical numbers (1908). The music for Mikael Lybeck’s The Lizard (Ödlan; 1909) and Wedding March from Adolf Paul’s Language of the Birds (1911) also fall into this category.

In the spring of 1909, Sibelius received a request from the famous Canadian dancer Maud Allan (1873–1956) to compose music for The Sacrifice, an Egyptian-themed ballet-pantomime she had written, which would be performed at the Palace Theatre in London. According to Erik Tawaststjerna, it may have been Ferruccio Busoni who suggested that Allan should contact Sibelius, as she had been Busoni’s piano pupil in Weimar and Berlin.[31]

Sibelius wrote to Aino from Berlin on 9 April 1909: ‘The scenario is very appealing to me, as it is a pantomime with music, my genre (not opera!).’[32] Interestingly, he seems to suggest that pantomime is his own genre on the basis of his earlier theatre music, although he had not composed music for a complete pantomime before. Nonetheless, Sibelius did not accept the offer, even though it was financially attractive. He wrote to Aino a couple of weeks later: ‘I shan’t go to England and nor shall I compose this dance score because I don’t want to take on any Oriental things now. And nowadays I only do what I have inspiration for.’[33]

At this point Sibelius professes not to be interested in Oriental subject matter, although he had composed music for Belshazzar’s Feast a few years earlier (1906). The decision not to participate is also notable in view of the enormous box-office success scored the following year by the Oriental pantomime Surumûn, directed by Max Reinhardt.

Sibelius had apparently agreed to compose a ballet-pantomime, however, as Maud Allan approached him again in the autumn, reminding him of his promise. They continued to correspond on this subject until the end of 1909, but in the end Sibelius refused.[34] Maud Allan was clearly interested in Sibelius’s music, as she danced to the accompaniment of Sibelius’s tone poem The Dryad in London in 1911.[35]

Although Sibelius had written to Aino that he was not interested in composing anything Oriental, he nonetheless wrote a Wedding March for Adolf Paul’s Old Testament Oriental play The Language of the Birds just two years later, in 1911.

Knudsen and the ‘accidental’ ballet-pantomime

Sibelius and Knudsen did not know each other before the Scaramouche project. The collaboration began, according to Knudsen, ‘by chance’, as becomes clear from the answer he gave in a press interview: ‘How did you come into contact with Sibelius?’ – ‘By chance. A friend of mine read the manuscript of a pantomime and said that no one but Sibelius could write music for it. Through Wilhelm Hansen’s music publishing company, negotiations started with Sibelius… ’[36]

The Dane Poul Knudsen (1889–1974) made his début as an author with the ‘tragic pantomime’ Scaramouche, written in 1911–12. It was published in 1914 in libretto form, but not in its entirety until 1922. According to Knudsen, his only two sources for Scaramouche were historical works about the theatre: the Danish writer Karl Mantzius’s Skuespilkunstens historie and the Italian Luigi Riccoboni’s Histoire du Théâtre Italien (1731). From these, he had taken the title role of Scaramouche; and he claimed that the text described a scene between Scaramouche and Pierrette.[37] In Knudsen’s text the traditional Pierrette character is renamed Blondelaine. In addition, the cast includes other stereotypes from the commedia dell’arte, such as Mezzetin, a variation on the servant character Brighella.

Knudsen’s life and works have received little attention. After his literary début, he worked as a writer, playwright, translator and, after completing a law degree, as a civil servant. His production also includes film screenplays, and he later collaborated with three other Finnish composers: Leevi Madetoja on the ballet-pantomime Okon fuoko (1927), Väinö Raitio on the ballet Vesipatsas (1930) and Tauno Pylkkänen on the opera Ikaros (1960). Knudsen also wrote texts for Austrian composer Emil von Reznicek (1860–1945), who worked in Germany: librettos for the operas Spiel oder Ernst (1930), Der Gondoliere des Dogen (1931) and Das Opfer (1932). In 1935 Sibelius and Emil von Reznicek were both recipients of the Goethe Medal (Goethe-Medaille für Kunst und Wissenschaft) and of the City of Hamburg’s Johannes Brahms Medal. These were not awarded to Jews or to those who were openly negative towards the Nazi régime. During World War II, Knudsen worked at the Danish Consulate in Hamburg.

The origins of Sibelius’s work have previously been discussed by Erik Tawaststjerna and by Fabian Dahlström in his explanatory comments to the published edition of Sibelius’s diary. Here I examine the origins of the work with reference to the diary, correspondence and newspaper articles.

Wilhelm Hansen had previously written to Sibelius a few times concerning other matters.[38] The letter concerning the Scaramouche commission, however, has not survived. In September 1912, Sibelius wrote in his diary: ‘Received a request to compose music for Poul Knudsen’s text’.[39] During the following days he made further diary entries concerning work on Scaramouche. [40] The fact that he started work straight away suggests that Sibelius had received either a synopsis or a version of Knudsen’s libretto manuscript with the letter from Hansen. The diary entry does not mention the nature or scope of the commission – aspects that would later cause problems.

In late September Sibelius travelled to the Birmingham Music Festival in England, at the invitation of Granville Bantock, to conduct his Fourth Symphony.

In the wake of the Scaramouche commission, Hansen had undertaken to organize a concert for Sibelius in Copenhagen. In October, Hansen wrote two letters to him the same day, one about the programme for this concert and the other about Scaramouche, which he referred to as a ‘ballet-pantomime’. This letter mentions the fee for the theatre performances suggested by Michael Trepka Bloch (1873–1938), a theatre agent and lawyer based in Copenhagen. At the same time Hansen declared that he was ready to publish the music. We can therefore surmise that at this stage Hansen acted only as an intermediary with Sibelius.[41] Trepka Bloch was probably the ‘friend’ mentioned by Knudsen who acted as a middleman between him and Hansen. As a result Trepka Bloch, whose name first appeared in this context in Harold Johnson’s Sibelius book in 1959, is often incorrectly listed in Sibelius literature as the co-author of the work.[42]

There followed an exchange of letters in which Hansen acted on Sibelius’s behalf and Trepka Bloch spoke for Knudsen. Communication between Sibelius and Knudsen took place through these middlemen, which made it more difficult to convey even simple information: Sibelius first wrote to Hansen, Hansen passed the information to Trepka Bloch and Trepka Bloch delivered it to Knudsen. Knudsen’s messages to Sibelius followed the same route in the opposite direction. This caused a variety of problems; for example, Sibelius did not receive clear instructions at the outset and did not have direct discussions with the librettist Knudsen. This was especially problematic because Knudsen revised his text several times.

In November Sibelius began planning an opera based on Juhani Aho’s novel Juha, with a libretto by Aino Ackté. He also toyed with another opera project, based on Adolf Paul’s play Blauer Dunst (Sheer Invention). Neither of these came to fruition.[43]

In November/December, Sibelius was in Copenhagen, where he met not only Hansen but also Knudsen and Trepka Bloch. He conducted the Fourth Symphony and other works, receiving negative reviews. Tawaststjerna states that the pile of reviews that awaited him when he returned home ‘ruined’ his birthday. Sibelius wrote in his diary: ‘47 years old today! – All hell let loose in the Copenhagen papers. I was denouced infernally. I can no longer keep my spirits up.’[44] In a letter that arrived after Sibelius’s birthday, Hansen suggested splitting the revenue three ways: Trepka Bloch, Sibelius and the publishing house would each receive a third, as was verbally agreed.[45] According to this, Knudsen would receive nothing directly, though we may assume that he would be have been remunerated by Trepka Bloch. Sibelius wrote in his diary: ‘Wilhelm Hansen wrote with the publisher’s proposal. You have to respond and out on the pressure (!) if it is to be successful now.’[46]

The same day, he responded to Hansen’s proposal, whereupon Hansen proposed half the fee immediately and half upon delivery of the work.[47] Sibelius signed the publishing contract in late January 1913. After receiving the contract Hansen commented that he expected to receive the manuscript in April. There is nothing in the text of the contract that specifies the scope of the work or when it should be completed. Nor is there any mention of the author of the text. Apart from defining the rights to the work, remuneration and so on, the contract merely states that the commission is music for the ballet-pantomime [!] Scaramouche.[48]

New text with spoken lines and Der Schleier der Pierrette

Before signing the contract, Sibelius had received a new libretto at the turn of the year 1912–13, including dialogue. He was disturbed by the idea that the spoken words could potentially ruin the pantomime, and he gave his reaction in a letter to Hansen.[49]

Knudsen, via Bloch and Hansen, stated that Scaramouche is purely a pantomime, and that the dialogue in the text, as in Der Schleier der Pierrette (The Veil of Pierrette) by the Austrian author Arthur Schnitzler (1862–1931), was only intended to serve as a guide for the actors, so that they could more effectively bring out the expressions and movements required.[50] Der Schleier der Pierrette, published in 1910, does indeed contain dialogue, but it is specified that the words are there only to assist the actors: ‘That which is presented as dialogue in the text is, of course, only expressed as pantomime.’[51]

In general, Sibelius’s progress on new compositions was closely followed in the Finnish press. In February, news of his new work Scaramouche was announced.[52] Sibelius was busy with other works, however – piano pieces, the second (G minor) Serenade for violin and orchestra and The Bard. He returned to Scaramouche in April, mentioning it in diary entries between 10 and 19 April, such as ‘working on the S. dance’ (17 April) and ‘forging the pantomime’ (19 April).[53]

Knudsen’s reference to Der Schleier der Pierrette as a model for Scaramouche – about the dialogue being used only as a guide – probably drew Sibelius’s attention to Schnitzler’s work. Then he read a synopsis of it and observed that Scaramouche’s plot was very similar. He sent a furious telegram to Hansen, saying it was gross plagiarism and wanting to withdraw from the contract.[54] As he mentioned in his diary: ‘Scaramouche is plagiarism. Have sent a telegram. A drama is brewing’.[55]

Hansen informed Michael Trepka Bloch and Poul Knudsen. In his reply, Knudsen explains the plot of Der Schleier der Pierrette, compares the two texts and apologizes. He admits certain similarities, but claims that he had written Scaramouche before Schnitzler’s Der Schleier der Pierrette appeared, and that an initial printed version of it had been made three years earlier, before the publication of Schnitzler’s work. He suggests an assessment by an ‘impartial arbitrator’ and concludes: ‘If he thinks my work is plagiarism, I would like the contract to be upheld (I can commit to submitting another text).’[56] He also commented: ‘But if he finds only small details that are reminiscent of Der Schleier der Pierrette, it could possibly be revised.’[57]

Der Schleier der Pierrette had been premièred on 22 January 1910 at the Dresden Royal Opera with music by the Hungarian Ernst von Dohnányi (1877–1960), and it was published the same year. Thereafter Der Schleier der Pierrette was performed in, for example, Vienna, London, Copenhagen, Berlin, Oslo and Budapest.[58] The work became popular with (in particular) Russian theatre directors (Vsevolod Meyerhold, Alexander Tairov).[59]

In Dresden, the main roles were played by opera singers, that of Pierrette being taken by the Finnish singer Irma Tervani (1887–1936), sister of Aino Ackté, whose singing career was centred in Germany.

Scaramouche, published in 1922, gives 1911–12 as its years of writing.[60] Interestingly, the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen performed Der Schleier der Pierrette in 1911, with Carl Nielsen conducting Dohnányi’s music.[61]

Meltdown – a through-composed work

Sibelius’s diary for May 1913 contains no references to progress on Scaramouche. In June he returned to the work. On 15 June he wrote: ‘I must start on Scaramouche in its original form’[62] and the following day: ‘Worked on the pantomime. Considered linear counterpoint!’[63]

This would suggest that Knudsen may have come up with a revised version of the text that was in some ways similar to the first one. He may have adjusted it as a result of the accusations of plagiarism. In any case, after receiving it Sibelius contacted Hansen and, according to Tawaststjerna, the final ‘meltdown’ came when it became apparent to Sibelius that he had to deliver a through-composed pantomime instead of three separate dances.[64]

Hansen replied that Trepka Bloch had shown Sibelius’s letter to Knudsen, whereupon Knudsen declared that the work should be through-composed and should closely follow events on stage, as in any mime ballet. In addition, it could be performed both in theatres and in opera houses; Knudsen uses the term ‘ballet-pantomime’ about the work, as in the contract mentioned above.[65]

In his reply, Sibelius demanded an increase in the fee for Scaramouche, pointing out that when he accepted the commission, he did not think he would need more than two or three days to compose it: ‘I did not think that the pantomime would be a through-composed work.’ Now that appeared to be the case, ‘my entire reputation is in the balance.’[66]

That same day, 21 June, Sibelius noted in his diary: ‘I ruined myself by signing the contract for Scaramouche. – Today things became so heated that I smashed the telephone. – My nerves are in tatters. What remains for me? Nothing. I have allowed one stupidity after another to weigh me down. Have written both to Breitkopf & Härtel and to Hansen (with a demand for an additional fee). But now I’m in a jam both as an artist and as a human being. How wretched!’[67] Nevertheless, a few days later he was back at work on Scaramouche[68] and wrote in his diary: ‘Hansen would release me from the Scaramouche contract, but Trepka Bloch – not a chance.’[69]

At the end of June, Hansen mentioned that he had forwarded a letter from Sibelius to Trepka Bloch and Knudsen, from whom he was awaiting a response.[70] While Sibelius was waiting (commenting in his diary: ‘Spending my time waiting for a decision concerning the pantomime’ [71]) he began composing Luonnotar for Aino Ackté.[72] [73] In August Sibelius made only a few diary entries, probably because he was hard at work on Luonnotar, which he completed on 24 August.[74] It was premièred at the Gloucester Festival on 10 September and in September/October Sibelius revised the score.

In early August Sibelius completed a small piano piece called Spagnuolo,[75] an occasional piece for the Hämeenlinna-based publisher Arvi A. Karisto’s Christmas magazine Joulutunnelma. The Spanish style of this piece is perhaps a spin-off from Sibelius’s work on Scaramouche which, as Knudsen’s text makes clear, features a bolero.

Sibelius returned to Scaramouche in September, when he received the fourth version of the text from Knudsen, and was already thoroughly fed up with it. He had been working on the basis of the third version of the text, and now drafted a letter to Knudsen: ‘I can no longer change anything without the whole musical structure collapsing. To revise the work according to what you just sent would take too long, and I no longer have the inclination for that – especially as I have already twice accommodated you by making revisions arising from additions from your side.’[76] Moreover, Sibelius had to work separately on the passages that were plagiarisms of Schnitzler. At this stage he planned for the pantomime to play for an hour, with two separate pieces, Danse dramatique and Canzone, that could be extracted. These titles suggest that Sibelius was already planning separate numbers, of which he later made piano versions (with different names).[77]

Understandably, receiving this fourth version made work on the piece frustrating, and it became increasingly burdensome, as the September and October diary entries reveal: ‘Scaramouche is tormenting me. It’s killing me’; ‘I can’t manage to finish the pantomime. I pay in blood for these commissions!’; ‘Working today on the pantomime that will never be finished.’[78]

Sibelius accepted commissions as a way of earning money, but they did not bring in enough, as he always had insufficient resources to fund his lavish lifestyle. His diary is full of entries on this subject. In May 1913 he wrote: ‘At present I have a staff of five servants, who cost me thousands when I take pay, board and lodging into account…’[79] He also questioned his standing as a composer. In July he wrote: ‘Bankruptcy and poverty are grimacing at me.’[80]

By November, Sibelius was apparently occupied intensively with Scaramouche, as he wrote in his diary: ‘Business matters are constantly interrupting my work on the pantomime.’[81] And after his birthday he continued: ‘Yesterday was my 48th birthday. Sic itur ad astra. – I was overworked and sick. Nervous in the extreme. Making a fair copy of the pantomime, i.e. composing it in its definitive form. What will become of this child?’[82]

On 19 December 1913 Scaramouche was ready, more than six months later than originally foreseen.[83] Two days later he sent it to Hansen along with a letter stating: ‘As you see, the original scheme has grown into a comprehensive work. To get it right has cost me much thought and work. In the form it now takes, I believe it will be successful. Generally speaking, I have thought of the stage as being full of activity – it’s not a work for actors who stand around waiting for gestures from on high.’[84]

Decades later, Sibelius told his faithful secretary Santeri Levas about the confusion surrounding the composition and the contract: ‘Poul Knudsen burst into my hotel room in the middle of the night with a lawyer and a contract… I signed it without reading it properly. It was only later that I realized that I had obliged myself to compose a large-scale work.’[85] Perhaps this was some kind of preliminary contract, as Sibelius was in Copenhagen in the autumn of 1912, and the lawyer who accompanied Knudsen was presumably Trepka Bloch. When Sibelius signed the official contract in January 1913, he was in Finland and the text of the contract defines the work only as a ballet-pantomime. It is also possible that Sibelius had not understood what the term ‘ballet-pantomime’ implied. Sibelius always uses the word ‘pantomime’ in his diary when mentioning Scaramouche, never the ‘ballet-pantomime’. Such confusion can occur when the parties are not in direct contact with each other.

Piano arrangements in Berlin

In early 1914 Sibelius spent more than a month in Berlin, working on a commission from the USA that became The Oceanides, and listening to what his colleagues were doing.[86] During this time he made piano adaptations of the Danse élégiaque and Scène d’amour from Scaramouche.

On the way to Berlin he stopped in Copenhagen, where he met his publisher Hansen. Scaramouche was discussed, and for the role of Blondelaine the famous Russian ballet dancer Anna Pavlova (1882–1931) was suggested. Pavlova had first appeared abroad in 1908 on a tour by the Imperial Ballets Russes organized by Edvard Fazer, and then with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes; she moved to London in 1913.[87]

Sibelius wrote to Aino on 8 January 1914 after arriving in Berlin: ‘With him, dear old Wilhelm Hansen, I had an hour-long meeting, which resulted in me being promised 1,000 kronor (although it doesn’t seem to be in the contract) in a few days’ time, after I’ve managed to deliver the arrangements. Otherwise they are very excited about the whole thing. And, believe you me, I fired them up. They plan to get Anna Pavlova or [illegible] to create the role. In any case, it looks very promising.’[88] A few days later Sibelius wrote again to Aino on this subject: ‘The more distance I have from the pantomime, the more I begin to believe in its success. Today, I finally finished the Danse élégiaque piano arrangement. They break my spirit, these “Valses tristes” , but – so be it.’ [89]

The next day he wrote in his diary: ‘Busy with the piano arrangements (Scaramouche). It’s true that I overexerted myself with the pantomime. To get back to normal I need rest. But I don’t have time for that. The American commission is urgent.’[90] He immediately wrote to Aino again: ‘The pantomime is excellent. But with all my heart I long to be rid of it. How good that I have finished it’[91] and then, in mid-January: ‘Now I have completed the piano transcriptions of Danse élégiaque and Scène d’amour and I sent them to Hansen today. Yesterday I worked until 3 a.m.’[92]

When Knudsen’s libretto was published, he sent it to Ainola together with a letter. It was forwarded by Aino Sibelius to Sibelius in Berlin in mid-January.[93] Sibelius did not mention receiving this, but a couple of weeks later he wrote to Aino: ‘If people take to the pantomime, we’ll be debt-free at a stroke. I’m intrigued.’[94]

Sibelius had no previous experience of working with Hansen, but the firm would go on to publish his last three symphonies and other works. The piano arrangements that Sibelius sent to Hansen appeared as late as 1921, as a consequence of the First World War. Later still, in 1925, he made an arrangement for violin and piano of the Scène d’amour.[95] While in Berlin Sibelius wrote a reminder to himself in his diary: ‘Some things in the pantomime must be re-orchestrated.’[96]

A massive score

Early in 1914, it was reported in both Denmark and Finland that Sibelius’s massive score for Scaramouche was ready, and the text was being translated into five languages.[97] This referred to the completion of Sibelius’s composition, not the appearance of the printed score, which did not happen until 1918. The printed score has three languages, French, German and English, including dialogue and stage directions.[98] The work is dedicated to the Danish dramatist and critic Svend Borberg (1888–1947).[99]

The term ‘massive score’ used in the news coverage is accurate, as this through-composed stage work runs to more than 200 score pages.[100] The duration of the piece is approximately 65 minutes. It is thus much longer than Sibelius’s early through-composed opera Jungfrun i tornet (The Maiden in the Tower). The incidental music to Shakespeare’s The Tempest is also more than an hour long, but is not continuous. The symphonies are all shorter than Scaramouche.

Scaramouche consists of two acts that play without a break, and are divided into 21 scenes (ten in the first act, eleven in the second). Several of the scenes last less than a minute, and the longest is scene 20 in Act II, which plays for thirteen minutes. It is scored for strings plus woodwind (2 flutes [piccolo], 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons), a brass section comprising just four horns and a cornet à piston, piano and percussion (timpani, triangle and tambourine). Sibelius has followed the instructions for dances contained in Knudsen’s text, and also makes use of leitmotifs. The work is not Wagnerian, however; it is more reminiscent or chamber music, delicate and lyrical. The musicians are divided into three groups: the main orchestra, a group of offstage players (Scaramouche’s troupe) and players among the dancers on stage.

The action is set at Leilon’s farmhouse and the events take place one evening and in the small hours. The pantomime’s theme revolves around a ball at the house and Blondelaine’s solo dances, so music is a central part of the plot. The first act contains the ball with musicians, the playing of Scaramouche and his trio, and Blondelaine’s dances. The second act includes Leilon playing the spinet and more of Blondelaine’s dances.

At the start of Act I we hear the music of the ball – in Sibelius’s score, a minuet. The host, Leilon, does not dance, and his wife Blondelaine complains about this to her admirer Mezzetin. During the festivities Blondelaine dances a bolero for the guests. A Spanish atmosphere is created not only by the bolero rhythm but also by the jingling of the tambourine. From outside we hear Scaramouche playing the viola (in Knudsen’s text, viola da gamba). Sibelius represents Scaramouche’s playing with chromatic viola and cello solos. Scaramouche’s troupe includes a boy playing the flute and a woman playing the lute.

Scaramouche is invited to play at the festivities and, while he plays the bolero, Blondelaine – observed by the ball guests – dances ever more passionately and erotically. The jealous Leilon drives Scaramouche and his troupe away, and then the ball continues with the guests dancing – in Sibelius’s score, a waltz. This waltz blends with Scaramouche’s playing, which entices and seduces Blondelaine.

At the beginning of Act II, Knudsen’s text gives no instructions about music. Leilon and his friend Gigolo are drinking wine after the guests have left, and Leilon reminisces about Blondelaine. Here Sibelius has composed an attractive, melancholy string theme that will later be transformed into a flute solo (Tranquillo assai). In Knudsen’s text the posthorn sounds to signal the departure of the post coach, and Gigolo leaves. In Sibelius’s score, the posthorn (represented by the cornet à piston) is heard offstage as instructed.

Blondelaine enters; the scene with her and Leilon contains hints of the flute theme from earlier. When Leilon has left, Scaramouche arrives to take Blondelaine away. Scaramouche does not play any music in this scene, but the Scaramouche theme is heard in Sibelius’s score. Blondelaine doesn’t want to go with Scaramouche and stabs him with a dagger, then hides his body behind a curtain.

Blondelaine (Lisa Taxell) stabs Scaramouche (Klaus Salin), Act II (1955)

© Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara

After this the music once again becomes an integral part of the events on stage. Leilon returns; Blondelaine takes him to the spinet, and he starts playing. The music heard is the minuet from the very beginning. Blondelaine begins to dance, stumbles and sees a trickle of blood running from behind the curtain. As she continues to dance, she imagines that she can hear Scaramouche playing in the room. Leilon reveals the body of Scaramouche behind the curtain and Blondelaine dances herself to death. Leilon loses his mind. At the end (the score is marked Grave), the boy and woman from Scaramouche’s troupe come looking for him, and find him dead. They leave, and the woman makes the sign of the cross.

After seeing the Copenhagen performance, Professor Rolf Lagerborg (1874–1959), an expert in Finnish moral-philosophical matters, wrote that ‘Scaramouche could be performed in church as a modern-day mystery play: it discourages people from sinful love more effectively than images of the horrors of hell.’[101] The piano transcriptions that Sibelius made focus on the bolero played by Scaramouche in Act I (Danse élégiaque) and the music from the scene at the beginning of Act II depicting Leilon’s love for Blondelaine (Scène d’amour).

Karen Vedel depicts Scaramouche as follows: ‘Familiar from folksongs, the plot is structured over the conflict between the tempered desire of the everyday and the allure of the unknown. In terms of the dancing it is best illustrated in the contrast between the Minuet and the wild dance spurred by Scaramouche’s tune, reaching climax in Blondelaine’s death-by-dancing. The dichotomy addresses the double function of dance as a manifestation of order vis à vis dance as a representation of madness, and points in symbolist terms to a bridging between the conscious and the unconscious by way of music while privileging dance as a site of corporeal expression.’ About the figure of Scaramouche she writes: ‘From the position on the fringes of the social world, he mocks the institution of marriage by bringing into focus the powerful symbiosis of dance, music and sexuality.’ Vedel sees Blondelaine as a dual role of both femme fatale (cf. Oscar Wilde’s Salome) and a figure comparable to Nora in Ibsen’s Doll’s House. ‘Serving a double function of the one hand pleasing the male gaze and on the other providing access to some of what is repressed in the family institution and gender roles of the bougeois world, dancing to Scaramouche’s tune is shown as transitory and fatal.’ [102]

The music’s suggestive power and erotic dancing

Scaramouche is described in the directions given in Sibelius’s score as ‘A little hunchbacked dwarf dressed in black’. In Knudsen’s text published in 1922, however, there is no description of Scaramouche’s appearance. The commedia dell’arte Scaramouche is not hunchbacked; that is a characteristic of Pulcinella. Apparently the idea is that the power of both music and musician are so great that they cast a spell on Blondelaine.[103]

In addition to writing music of great suggestive power associated with Scaramouche’s playing, Sibelius was a masterful composer of dances. The dance forms found in Scaramouche – the minuet, bolero and waltz – were all ones that Sibelius had used in the past.[104]

Cecil Gray has pointed out: ‘The influence of Johann Strauss… is not confined to the waltzes themselves, but can be detected throughout his work in the form of a strong predilection for themes which make use of the characteristic technical device of the Viennese waltz called the Atempause – the strongly marked rest, like a catch in the breath, which precedes the final note of the bar.’[105] The influence of Johann Strauss’s waltzes is a consequence of Sibelius’s studies in Vienna in the early 1890s.

Sibelius had previously composed an accelerating ‘death dance’ (danse macabre/Totentanz), comparable with the one performed by Blondelaine, in his music for Järnefelt’s play Kuolema: Valse triste.

According to Kari Kilpeläinen, Scaramouche may contain material from sketches for Pohjola’s Daughter (Op. 49, 1906) as well as from the unfinished orchestral song The Raven, material from which was also used in the Fourth Symphony (Op. 63, 1911).[106] Researchers have pointed out that Scaramouche has connections with several other works by Sibelius too. After the appearance of the first recording, Veijo Murtomäki reviewed the CD in Helsingin Sanomat: ‘It contains expressive chromaticism, stridency in the manner of the Fourth Symphony, a thrilling depiction of the anguish of the soul’.[107] According to Erkki Salmenhaara, the chromatic theme played by Scaramouche resembles the Fifth Symphony[108] and according to Robert Layton it has links with the Seventh.[109] In addition, both Murtomäki and Layton have pointed out its connection with the impressionism found in The Oceanides. Swanwhite and the violin Humoresques have also been mentioned in this context.[110]

Salmenhaara writes that Scaramouche was ‘almost the first expressionist work to have been performed on our main stage [the Finnish National Theatre]’.[111] It has also been compared to works by Richard Strauss. Ralph W. Wood has pointed out similarities with Der Rosenkavalier, Robert Layton to Der Bürger als Edelmann and Marc Vignal to Ariadne auf Naxos.[112] These were all completed just before Scaramouche, and all had been directed by Max Reinhardt.[113]

Scaramouche has also led researchers to speculate about what kind of operas Sibelius might have written at that time.[114] Moreover, in 1947 Ralph W. Wood: ‘It brings into one’s head a very unexpected speculation about what Sibelius might have done as a composer for films’.[115]

Der Schleier der Pierrette and Scaramouche

As the similarity between Der Schleier der Pierrette and Scaramouche overshadowed Sibelius’s compositional process from the outset, it is appropriate to compare these two works, as their kinship continued to play a part in their performance history.

The plot of Der Schleier der Pierrette is briefly as follows: Pierrette is forced by her parents to marry the old and rich Arlecchino (Harlequin), even though she loves the impecunious Pierrot. In the middle of their wedding, Pierrette escapes to be with her lover, with the intention of dying with him (cf. Romeo and Juliet). Their joint suicide by poison does not take place because of Pierrette’s hesitation; only Pierrot dies after drinking from a poisoned cup. Pierrette returns to the wedding party and to Arlecchino, who in a fit of jealousy has smashed the musicians’ instruments. Pierrot’s ghost appears to Pierrette at the wedding reception and tells Pierrette to retrieve the veil she had left at Pierrot’s house. Arlecchino follows Pierrette and locks her in a room with the dead Pierrot. Pierrette loses her mind and dances herself to death.

Scaramouche and Der Schleier der Pierrette certainly exhibit similarities. Both take place in a single evening and the early hours. Both feature commedia dell’arte characters and a love triangle comprising one woman and two men. They both contain a ball, where the woman meets another man and dances herself to death in front of that man after having played a part in his death. In addition, a dead man appears in each of the women, either as a vision (Pierrot) or as sound (Scaramouche playing). They even both feature Gigolo, a friend of Leilon’s in Scaramouche and the ‘Tanzmeister’ who organizes the wedding dance in Der Schleier der Pierrette, listed as a ‘young man’ in the dramatis personae.[116]

Both texts include a female death dance, a danse macabre. In the early 20th century, several works were published in which a woman dances herself to death, most notably Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Elektra, with music by Strauss, premièred in 1909, and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, premièred by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris in the spring of 1913 – the very time when Sibelius was working on Scaramouche.

Finally, both Schnitzler’s and Knudsen’s pantomimes differ in one respect from the commedia dell’arte tradition: they are both horror stories in the turn-of-the-century style.

Performance plans

Karen Vedel, who has studied the performance history of Scaramouche’s Copenhagen première, has stated that Knudsen’s text was suggested to the Royal Danish Ballet as early as 1912. The ballet master Hans Beck (1861–1952) then rejected it because he believed it lacked ‘any possibility for pantomimic or gesture actions.’[117] The previous year, 1911, Beck had devised the choreography for Der Schleier der Pierrette.[118] At this stage, Sibelius’s music had not yet been composed; it is likely that he did not receive the commission until after the rejection, as negotiations went on until the end of 1912 and Sibelius signed the contract in early 1913.

As mentioned above, when the composition was complete Sibelius met Wilhelm Hansen in Copenhagen, on his way to Berlin, in the early days of 1914, when they discussed getting Anna Pavlova to play Blondelaine. After this meeting, Hansen sent Sibelius a letter stating that Kay Nielsen (1886–1957) had been chosen as costume designer.[119] Nielsen was Danish but had studied in Paris and was working at the time in London as an illustrator. His artwork from London includes drawings for stories such as The Sleeping Beauty and Bluebeard.

In October that year Knudsen sent Sibelius drawings for Scaramouche.[120] Hansen, too, kept Sibelius informed, and announced in December that Knudsen and the costume designer (presumably Kay Nielsen) had not reached agreement about in which era the performance should be set or the costumes required.[121] He also explained that he did not know the address of Betty Nansen (1873–1943). The famous Danish actress Nansen had also visited the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki but was by then working in the United States, where she made several silent films between 1913 and 1917.[122] Hansen and Sibelius had probably considered her for the role of Blondelaine, along with the ballet dancer Anna Pavlova. At this stage, however, the plans were not taken any further. In any case, the programme of the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen had once again included Der Schleier der Pierrette the previous season (1913–14).[123]

After this, a performance in Finland was also considered. In 1916, both the Finnish National Theatre and the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki simultaneously planned to give the première of Scaramouche.[124]

In February 1916, Sibelius wrote in his diary that the Swedish Theatre was interested in performing Scaramouche.[125] In April, the theatre’s board of directors decided to contact Wilhelm Hansen for information about Sibelius’s score. The performance was planned for the theatre’s next season, and at the August board meeting, it was decided to schedule it in March 1917.[126] Furthermore, in September it was reported in the press that Scaramouche would be performed during the 1916–17 season.[127]

This news came as a surprise to the Finnish National Theatre, which had already contacted Hansen, and had asked for and been promised the world première. After reading the news reports, the theatre’s director Jalmari Lahdensuo immediately wrote again to Hansen, but did not receive a reply; the board therefore decided to wait for Hansen’s answer. Scaramouche was not mentioned in the board meeting minutes in the next few months, so apparently Hansen did not respond.[128] Earlier that spring, Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Everyman had been discussed at the National Theatre’s board meeting, and it had been decided to include it in the programme, with music commissioned from Sibelius. In this context, Sibelius and Lahdensuo are also likely to have discussed Scaramouche.[129]

Hansen did not reply to the Finnish National Theatre, but only to the Swedish Theatre. In October the theatre’s management discussed Hansen’s letter to the artistic director, Adam Poulsen (1879–1969), stating that Sibelius would be keen on having Scaramouche premièred at the Swedish Theatre, and that Hansen wanted to take the composer’s wishes into account as long as an agreement could be reached with the theatre’s board. The material was currently being published, but Hansen could not say exactly when it would be ready.[130]

The Danish actor Adam Poulsen had just moved from the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen to Helsinki, where he worked as director of the Swedish Theatre from 1916 until 1919. Poulsen, who had studied under Max Reinhardt in Berlin, came from a celebrated Danish acting family. His uncle Olaf Poulsen had visited Helsinki to act at the Swedish Theatre in 1897, and Adam himself had visited in 1914.[131] In his memoirs Poulsen describes a visit to Ainola during his Helsinki years, and mentions that he had met Sibelius before, at Alfred Wilhelm Hansen’s villa in Copenhagen.[132] [133]

There are several reasons why Sibelius might have wanted the première of Scaramouche to take place at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki. First of all, Adam Poulsen had contact with Sibelius’s Danish publisher. Secondly, when Hansen wrote that Sibelius wanted Scaramouche to be performed at the Swedish Theatre, Sibelius was already working on the Everyman commission for the National Theatre. He might therefore reasonably have expected his music to be performed simultaneously on two different stages in Helsinki.

After receiving a letter from Poulsen, Hansen immediately wrote to Sibelius about Knudsen’s suggestion that Scaramouche should be performed at the Swedish Theatre complete with spoken dialogue. This would be like ‘a dress rehearsal to assess its impact’.[134] Apparently Knudsen thought the Finnish staging would serve as a trial run for a Copenhagen performance.

Nonetheless, Scaramouche was not performed in March 1917; it was postponed until March 1918, with, in reserve, ‘Der Schleier der Pierrette, pantomime by Ernst von Dohnányi’.[135] The artistic director, Adam Poulsen, may well have seen Der Schleier der Pierrette at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen in 1911 or its repeat performance there in the 1913–14 season, with his brother Johannes Poulsen in the role of Arlecchino. Adam Poulsen himself was director of the Dagmar Theatre in Copenhagen from 1911 until 1914.

In May, Poulsen was authorized to sign a contract on behalf of the theatre with Wilhelm Hansen for the performance of Scaramouche, and performances – of Scaramouche or Der Schleier der Pierrette – were planned for the period from 16 March to 14 May 1918.[136] Plans for the performance were thus coming along nicely.

In September, when the theatre announced its programme for the coming season, it included: ‘An original Finnish work, Jean Sibelius’s pantomime Scaramouche or, if the publisher keeps us waiting for the material, Arthur Schnitzler and Ernst von Dohnányi’s Der Schleier der Pierrette.’[137] The extra mention of the publisher is an expression of irritation with Hansen because Sibelius’s score had not yet been published. Moreover, the theatre had openly juxtaposed Scaramouche and Der Schleier der Pierrette, thereby drawing attention to the similarity that Sibelius had remarked upon and tried to change when composing the music. This juxtaposition cannot not have been to Sibelius’s liking. Subsequent board meetings, from October onwards, discussed only Der Schleier der Pierrette.[138]

In any case, Scaramouche could not have been performed in the spring of 1918, as Sibelius was still proofreading the score from March to September 1917, and it did not appear in print until December 1918. But in the end the programme did not include Der Schleier der Pierrette either. Owing to the Finnish Civil War, the theatre’s activities were curtailed, and it closed completely in the spring of 1918 for more than three months.[139] Immediately after the Civil War, the minutes of the Swedish Theatre do not include plans for either Scaramouche or Der Schleier der Pierrette for the 1918–19 or 1919–20 seasons.[140]

In the end Der Schleier der Pierrette was not included in the Swedish Theatre’s schedule until 1928, when the leading roles were played by guest actors – Mary Paischeff (Pierrette) and Alexander Saxelin (Pierrot), famous dancers who had trained at the St Petersburg Ballet School.[141] Scaramouche was, however, never performed at the Swedish Theatre.

Problems with publication

By early 1917 Sibelius had proofread the first sixteen pages of Scaramouche, and in March he continued with pages 17–50.[142] He wrote to his friend and patron Axel Carpelan: ‘Yesterday I finally received the first pages of proofs for Scaramouche. Let’s see what comes of this child.’[143]

By mid-April, the rest of the proofs had arrived, and Sibelius was ‘downright impressed’ to see the big pile of sheet music.[144] When reading the proofs, however, he was far from satisfied. The notation was full of errors and the printing was bad: ‘Read the Scaramouche proof. A terrible effort; I could scarcely imagine anything more miserable.’[145] The task of making corrections was laborious and took a long time. In July the second proof arrived and in September came the third.[146] In mid-September Sibelius sent the third corrections to Hansen.[147]

The score was finally published in December 1918 and the parts a few months later, in February of the following year. The publication of Scaramouche involved a number of separate print runs, as is shown by a letter from Hansen to Sibelius in February, mentioning that the orchestral parts had been printed, the orchestra score had come out some months previously, and the piano version had been engraved and was ready to be printed at any time. Librettos in Swedish, German and French were already printed, and English and Danish ones were almost ready. Therefore, Hansen said, preparations could be made for the pantomime to be performed the following autumn.[148]

The letter says that Hansen began preparations because, after the score had appeared, the première was planned once more at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen. Karen Vedel writes: ‘When Scaramouche was resubmitted for consideration by the Royal Theatre in 1919, spoken dialogue had been added to the previously purely pantomimic libretto. Moreover, it was accompanied by a newly written score by Sibelius. The censorship still found the work to be, in certain parts, too similar to Der Schleier [der Pierrette]. However, the prospect of performing the score by the renowned composer persuaded Gustav Uhlendorff, Beck’s successor as ballet master, to accept Scaramouche.’[149]

Notably, Der Schleier der Pierrette was once again included in the theatre’s schedule in the 1918–19 season.[150]

In June 1919, Sibelius attended the Nordic Music Days in Copenhagen and, according to Tawaststjerna, met the theatre conductor Georg Hoeberg (1887–1950), with whom he went through the Scaramouche score in preparation for the première.[151] The following month Sibelius wrote in his diary that he had received payment from Hansen for Scaramouche,[152] and that ‘Hansen is pleasant enough, but they cannot be counted on. There are middlemen involved who do not wish me well.’[153] By ‘middlemen’ Sibelius may be refering to Trepka Bloch and perhaps also to others who were in contact with Hansen.

Despite the plans for a performance in Copenhagen, Hansen was actively trying to arrange one in Helsinki too. In October 1919 he wrote to Sibelius that he hoped to secure a performance of Scaramouche in Helsinki during the winter.[154] In November, he announced that a director’s manual (Regiebok) had been prepared by Svend Gade.[155] This manual could be copied and then used in a theatre in Helsinki. Gade’s manual indicates that 100 lines were to be spoken.[156] But, as we have seen, Scaramouche was no longer in the schedules of the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki, and its director Adam Poulsen had by then moved back to Copenhagen.

In February 1920 it was reported in Hufvudstadsbladet that Scaramouche would be performed at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen ‘shortly’. In this context it was reported that the Finnish Opera had also planned to put on Scaramouche but, because the lead role was a female dancer, the plans had to be put on hold until the opera had the appropriate resources.[157] [158]

The same day, Sibelius wrote in his diary: ‘Scaramouche will soon be performed by the Royal Theatre [in Copenhagen]. I’m like Thomas [a doubting Thomas] about its success despite my splendid music.’[159] More than two years were to pass between this diary entry and the news reports (‘shortly’) before Scaramouche would finally be premièred.

The Copenhagen première

The first performance of Scaramouche took place at the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen on 12 May 1922. It was directed by Johannes Poulsen (1881–1938), whose brother Adam had previously been director of the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki and had tried to organize the work’s première in Helsinki. The choreography was by Emilie Walbom (1858–1932), who was the first woman to do choreography for the deeply traditional Royal Ballet in 1906 and had done so several times since then. The set and costumes were by Kay Nielsen and the orchestra was conducted by Georg Hoeberg (1872–1950). Johannes Poulsen and Kay Nielsen also collaborated on The Tempest with Sibelius’s music at the same theatre in 1926.[160] Poulsen, Walbom and Nielsen had worked together previously.[161]

Royal Danish Theatre, Copenhagen (c. 1900)

Scaramouche was the first ballet-pantomime that Poulsen directed, and he also performed the title role.[162] Originally, the job of directing Scaramouche had been offered to Max Reinhardt and Mikhail Fokine (1880–1942), a former dancer-choreographer with the Ballets Russes, who had both turned it down.[163] [164]

Kirsten Jacobsen, who has studied Johannes Poulsen’s work, notes that he was a modernist among Danish directors, influenced by Max Reinhardt and Edward Gordon Craig.[165]

The performance included dialogue, just as Sibelius had feared when he had received the revised libretto. The dialogue was part of a deliberate ‘experiment’ involving all aspects: pantomime, speech, music and dance.[166] Karen Vedel remarks: ‘Scaramouche combined several complementary styles, drawing on symbolism in the stage direction, on art nouveau in the set design and on expressionism in the choreography… it placed equal importance on the music, the set design, the mime/dance and the dialogue.’[167]

In the role of Blondelaine was Lillebil Ibsen (née Christensen), who had previously danced at Max Reinhardt’s theatre. She came to rehearsals at short notice and was permitted to design her own dance moves, incorporating the choreography by her former teacher Emilie Walbom.[168] Poulsen particularly praised Lillebil’s performance.[169] According to the reviewer in Politiken, however, she lacked some of the wildness and temperament needed in the closing scene.[170] [171]

Reviewers of the première compared Scaramouche to Der Schleier der Pierrette, but the difference was that Scaramouche included dialogue and also shouting when more intensity was required.[172] The treatment of the dialogue was compared with Maurice Maeterlinck.[173] The reviewers no doubt remembered the production of Der Schleier der Pierrette in 1911, choreographed by Hans Beck, in which Poulsen had played the role of Arlecchino,[174] which was repeated in the 1913–14 and 1918–19 seasons.[175]

Both Kirsten Jacobsen and Tawaststjerna note that reviews of Scaramouche used the word ‘perverse’ . When writing about the sets and the costumes, the word ‘half-perverse’ (‘halvpervers’) was mentioned;[176] the ‘unexplored and eternal passion’ of Sibelius’s music ‘was manifested in black mysticism and incomprehensible visions’ and contained ‘a demonic wildness and his refinement almost bordering on perversity…’[177] Jacobsen has observed that at the première Sibelius’s music attracted attention and appreciation.[178] Indeed, the music was even rated as excellent.[179]

The Finnish press wrote about the performances and the reception received by Sibelius’s music in Denmark.[180] Svenska Pressen clearly headlined the comments in the Danish papers: ‘Sibelius won a great victory as a dramatist – The whole score is a masterpiece – Gripping poetry. ’ A few days later, Sibelius noted its success in his diary.[181]

Both Jacobsen and Ibsen (in her memoirs) report that the intention had been for Sibelius to conduct the music at the première, but he cancelled owing to illness.[182] Sibelius’s diary contains no mention of a trip to Copenhagen. In late April he wrote about having flu symptoms, and in early May he learned that his brother Christian was suffering from an incurable illness that would lead to his death two months later. Perhaps these were the reasons for his cancellation.[183]

Scaramouche remained in the Copenhagen schedules for a couple of years, during which time it was performed at the Royal Theatre 26 times, with various dancers in the role of Blondelaine.[184]

After the première, Hansen wrote to Sibelius: ‘Scaramouche was a great success yesterday… We’re working towards a performance at the Staatsoper in Dresden, Grand Opéra in Paris, Coven [sic] Garden, the Operas in New York and Stockholm.’[185]

Hansen clearly expected Scaramouche to succeed, as after the première he issued some piano arrangements by Eyvind Alnaes: Scène d’amour (1922) and Choix de mélodies tirées de la Pantomime tragique Scaramouche (1923). Even before that, a piano version of Scaramouche by the Danish composer Otto Olsen (1919) and Nicolaj Hansen’s arrangement of the Scène d’amour for salon orchestra (1920) had been published. The piano adaptation by Sibelius himself of the Scène d’amour, which he had supplied to Hansen as early as 1914, appeared in 1921 together with the Danse élégiaque.[186]

The first Helsinki performance: 19 March 1923

The next place Scaramouche was performed was Helsinki, where it had its Finnish-language première at the National Theatre on 19 March 1923. Surprisingly, this Finnish performance has never been researched in detail before, even though it involved music by Sibelius and a theatrical event that was announced in advance in Helsingin Sanomat as ‘an extremely interesting and eagerly anticipated première.’[187] The following day it was even front-page news, with performance photos (Uusi Suomi, 20 March 1923), and several reviews were published.[188]

As we have seen, the Finnish National Theatre had been interested in securing the world première of Scaramouche in 1916, and had received Hansen’s consent for this, but nothing had come of the plan and Hansen had been in contact with the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki instead. After the Copenhagen première, though, Hansen offered Scaramouche to the National Theatre. Around the same time the Finnish Opera planned to perform it, and this was reported in the press.

National Theatre, Helsinki (1902–05)

(CC BY 4.0)

The project was first discussed by the theatre’s board in late August 1922. The theatre’s director, Eino Kalima, was of the opinion that it belong at the Finnish Opera, and he had therefore held talks with the opera’s director, Edvard Fazer. Sibelius, for his part, had been in contact with Kalima and, as a result, Kalima submitted the project to the board: ‘Only when the composer wanted it to be performed by the National Theatre did he [Kalima] propose that it be included in the programme.’[189] Sibelius may also have had a personal interest, as his daughter Ruth Snellman acted at that theatre.

Hansen first contacted Sibelius, and then sent information about the performance rights directly to the theatre, but did not receive a response. In mid-August, Hansen asked Sibelius to contact the board.[190] A week before the board meeting on 31 August 1922, it was reported in the press – in the context of the coming season’s schedule at the Finnish Opera – that ‘negotiations are ongoing about the performance of Sibelius’s pantomime Scaramouche.’[191] Apparently, Kalima had discussed the matter with Edvard Fazer, as at the same time the Finnish Opera revealed its plans; its ballet section had started its operations at the beginning of the year with a performance of Swan Lake. At the Finnish Opera’s board meeting in the spring of 1922, the conductor Robert Kajanus suggested performing Scaramouche, but the matter was left undecided.[192]

Probably owing to Sibelius’s influence, Hansen offered Scaramouche to the Finnish National Theatre at a cheaper rate than usual. Kalima was assigned the task of contacting the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra to play the music, and had to ‘provide a libretto translation’.[193] As the theatre did not have its own orchestra, it collaborated with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra which, in addition to giving its own concerts, also played at the Finnish Opera and at theatre productions.[194] Thereafter things moved ahead swiftly: the next board meeting in September discussed the draft contract received from Hansen. [195] Subsequent minutes from 1922–23 contain no further references to Scaramouche.

Direction and choreography for the production were entrusted to Maggie Gripenberg (1881–1976), a pioneer of the art of dance in Finland, who had studied eurhythmics under Émile Jaques-Dalcroze in Dresden.[196] The set design was by Eero Snellman and the costumes were by Matti Warén. The visual effect was described as ‘colourful’.[197] [198]

Ruth Snellman as Blondelaine and Einar Rinne as Scaramouche

© Finnish Theatre Museum Archive

The role of Blondelaine was played by Sibelius’s actress daughter Ruth Snellman (1894–1976), who was engaged at the theatre. She rehearsed the dancing for the role for three months[199] but, as many critics pointed out, the role really needed a performer who was primarily a dancer.[200] Her performance was praised and was consistently described as charming and beautiful. But, like Lillebil Ibsen, ‘Madame Snellman’s temperament was insufficient for the powerful climax in the closing act.’[201] This was Ruth Snellman’s first important role in a play for which her father had composed the music. Later she played Ariel in The Tempest (1927), Swanwhite (1930) and Paramour in Everyman (1935). In her memoirs, she openly admits that ‘as a young actress I got the role of Blondelaine in Scaramouche because my father had composed the music.’[202]

Leilon was played by her husband Jussi Snellman (no relation to Eero Snellman), and Scaramouche by Einar Rinne. Scaramouche divided critical opinion: some emphasized his ‘gloomy imagination’ and others saying he was portrayed as a ‘robber type’ instead of ‘having a mystical, mysteriously fascinating power.’[203]

Einar Rinne as Scaramouche

(© Finnish Theatre Museum Archive)

In general Sibelius’s music was praised, but Knudsen’s text came in for criticism: ‘It is surprising that Sibelius could have been inspired by such a text’.[204] The spoken dialogue used at the performance was confusing: ‘The main fault with yesterday’s performance was that it was too much talk and too little real pantomime’;[205] ‘unusually high demands were placed on the performers, who actually had to be ballet artists and actors at the same time.’[206]

The music was played by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Tauno Hannikainen (1896–1968). Evert Katila wrote in Helsingin Sanomat: ‘Most of the words spoken on stage tend to be drowned out by the orchestra; you hear that something is being said, but actually understanding it requires some effort. It might be advisable to play those parts of the score that accompany dialogue piano or pianissimo, no matter what it says in the score.’[207] This comment illustrates the problem that Knudsen caused by adding dialogue.

The critics paid particular attention to the beginning of Act II. The music critic and composer Lauri Ikonen wrote: ‘The strongest passages were the “wordless” ones, such as the fine, atmospheric portrayal of Leilon’s troubled mood with the flute solo.’[208] The theatre critic Hjalmar Lenning took the view: ‘The most appealing and touching part of this beautiful music is the depiction of Leilon’s sorrow in the second act and his reunion with Blondelaine.’[209]

Unlike in the case of the Copenhagen performance, the reviews do not mention the ‘perversity’ of the performance or the music. Another interesting difference is that, despite being critical of the text, the critics did not note the connection with Schnitzler’s Der Schleier der Pierrette. Either the critics were unfamiliar with that work or the critics did not point out the plagiarism out of respect for Sibelius.[210]

Despite the positive critical reception of Sibelius’s music and the performance itself, the production failed to attract a large audience. Scaramouche shared a programme with the première of the one-act play Hirsipuumies by the Swedish-speaking Finnish writer Runar Schildt. The newspaper Karjala in Vyborg, the largest provincial newspaper outside Helsinki in the 1920s, reported: ‘Of course there was a full house on the first night, but when Hirsipuumies-Scaramouche was performed for a second time, only a negligible quantity of tickets was sold. This won’t be a box-office hit.’[211] The total number of performances – over a five-week period in March and April – was just eight.[212]