Scenes from the Kalevala

Leevi Madetoja: Kullervo, Op. 15

Uuno Klami: Kalevala Suite, Op. 23

Jean Sibelius: Lemminkäinen in Tuonela, Op. 22 No. 2 (1897 version – world première recording)

Tauno Pylkkänen: Kullervo Goes to War

Lahti Symphony Orchestra / Dima Slobodeniouk

BIS-2371

This is an interesting new SACD from Sibelius-champions BIS, compiling some older and more recent recordings revolving around the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. While the Sibelius piece (a world première recording) may be the obvious draw, the other pieces are at least of equal interest. In a way, absorbing as the Sibelius recording is, it is almost (but only almost – after all I am an inveterate Sibelius fan!) a shame the Sibelius piece is on the SACD, as there are other Kalevala pieces (not by Sibelius) that would have suited this project very nicely, like Robert Kajanus’s symphonic poem Aino (reissued in the BIS Sibelius Edition in the final CD ‘Around Sibelius’, which might explain its absence here) or Aulis Sallinen’s ‘Lemminki and the Maidens of Saari’ (a part of the longer opus, From the Iron Age, Op. 55, which is arranged from music for a Finnish TV series based on the Kalevala). But as it stands, this SACD offers rich ground to explore. Thematically, two pieces are about Kullervo, the tragic hero of the epic, one specifically about Lemminkäinen only, and one broader suite encompassing a number of scenes from the epic, though interestingly it has one movement titled ‘Lemminkäinen’s Cradle Song’ which corresponds directly to the slower middle part of Sibelius’s piece.

Let us start with the first piece, Leevi Madetoja’s Kullervo, Op. 15, written in 1913. It is a dramatic composition that starts with a call on the horns, like to war or a hunt (indeed, a horn in both these capacities is instrumental in the story of Kullervo[1], both as a symbol of the war he wages against his uncle as well as the means with which he gains revenge on Ilmarinen’s wife). The symphonic poem is obviously not a scene-by-scene re-telling of the six runos of the Kalevala that deal with Kullervo’s story[2], but more an atmospheric and emotional condensation of his story: the horns reflect his bellicose and rash nature, how he is never happy until his uncle Untamo is killed. In all he does Kullervo is luckless, filled as he is with great strength and anger. His downfall is when he unwittingly seduces and sleeps with his sister; on finding out she drowns herself. Kullervo eventually kills himself on the very spot his sister drowned herself. The various themes of the music reflect the searching, restless nature of the hero. The slower, more lyrical passages, in parts reminiscent of Tchaikovsky’s pathos, if a lot briefer, reflect short moments of respite such as when Kullervo finds his family, thought dead, alive again – or (towards the end) his brief moment of bliss in the arms of his sister. The end is hastened on by clattering from percussion and wind instruments, reminiscent of Kullervo’s sledge speeding through the snow to his doom, marked by the brass. A tragic, funereal theme takes over as the hero takes his own life and the horns sound once more, more pensively and doom-laden, and the whole piece ends in a very muted way, much like Väinämöinen’s final comment on the matter: ‘Poor Kullervo. That’s what happens when the hand that rocks the cradle does not care. The boy may grow up, but the lack of love will stunt him. He’ll be brawn, but no brain.’[3] All in all the piece is very much in the romantic tradition of symphonic poems such as those by Antonín Dvořák, with a vividness of depiction worthy of Mussorgsky.

Uuno Klami goes a very different way with his Kalevala Suite. As he himself stated, he was conscious of not treading ground Sibelius had marked previously, so sought inspiration from modern primitivism instead. Although only completed in its entirety in 1943 (a four-movement version was finished in 1933), the work hearkens back to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and similar pieces, although it is musically less complex. The first movement, ‘The Creation of the Earth’, grows slowly, and almost stilted, the woodwind carrying the main melody for large stretches, the other instruments accentuating growth and development of earth, plants, animals, until the strings race life along. The burgeoning life comes to a head in an inescapable, almost orgiastic crescendo, strangely reminiscent of Holst’s ‘Mars’ – life and destruction lie close together. ‘The Sprout of Spring’ is a calmer piece, with horns calling nostalgically, intermittently, and not at all the wild profusion we might have expected after the first movement. The third movement, ‘Terhenniemi’ (the cloud-encompassed headland), begins with slight dissonant chords, setting a scene of greater mystery, which rapidly dissolves to a lively melody with strings and woodwind dancing together to open into a pastoral that paints a picture of the landscape of Kaleva District. After this general introduction about the completion of the land (which does not even take up one runo in the Kalevala), the suite focuses on two specific events: Lemminkäinen’s resurrection at the hands of his mother (he was chopped into eight pieces by a son of Tuoni after having been shot by Märkähattu[4]) and the forging of the magical Sampo, an object central to the poem that brings fortune and riches. Predictably, ‘Lemminkäinen’s Lullaby’ is a muted, mellow and slow piece of music, which is nonetheless haunting in its gently undulating melody that captures both the rocking of the mother and the waves of Tuonela’s dark stream. It is more hesitant and darker than Sibelius’s corresponding piece at the heart of ‘Lemminkäinen in Tuonela’. The final movement describes how Ilmarinen forges the Sampo: from quiet beginnings the orchestra rises in lyrical passages, much like the flames which bring forth the magical mill. The problems of the Sampo’s forging (Ilmarinen has to try four times before the Sampo is finally made) are hinted at with occasional dissonant chords from the brass and the forging with percussion that Verdi would have approved of. The final shaping has the music come together from awkward, ‘square’ bursts to one whole glorious outburst where hammer rings turn into bells.

After its first performance, Sibelius revised (and shortened) his Lemminkäinen suite; despite resounding success with the public, who applauded after every movement (who would dare nowadays?), one critic (Karl Flodin, Finland’s most eminent music critic) complained that the piece dragged on for too long. This possibly led to the revision and shortening to what we have on this SACD. The revised version was premièred in Helsinki on 1 November 1897 with Sibelius himself conducting, to general dismissal from Flodin (who deemed it depressing and ghoulish), but otherwise ecstatic approval from the audience and most critics, who called it a symphony, accepting its formal integrity and aspirations. Flodin’s criticism obviously stung, because Sibelius would not publish or perform the entire suite until he had made a third revision in 1939. Compared with the original version, which is much more expansive and slow-moving, the 1897, second, version cut about 100 bars (approximately a quarter); an initial dreamy 32-bar (approximately one-and-a-half-minute) introduction was dropped completely, and the second version started with the now familiar dark and frantic tremolo strings that set the scene of the movement in Tuonela, the underworld of the Kalevala. The orchestration was also changed, most notably the harp accompanying Lemminkäinen’s lullaby, which one reviewer of the première in 1896 had commented on[5], was removed. The ending (after the lullaby) remains a strong, almost triumphant reiteration of the opening theme, the tuba not having been cut in this version as it was from the 1939 version, suggesting death has the final word, however alive Lemminkäinen may be after the spells of his mother. The result is a tighter piece of music, that conveys the threat of Tuonela and Lemminkäinen’s death more directly, as well as his subsequent sewing together and resurrection by his long-suffering mother.

Tauno Pylkkänen’s Kullervo Goes to War, written in 1943, is a fast-paced dramatic piece of music, where brass and drums play pivotal roles at either end of the composition to underline the martial character of the piece. True to the source, lyricism and comedy break through at times: for example, before setting out Kullervo asks his family whether they will miss him and all except his mother respond in the negative. Then, while on his way, the young hero is overtaken one by one by the news of the death of his family, the message for each family member reaching him a little further along his path until finally he hears of his mother’s death. These are the basis for the more quiet and sad central parts of the piece, that resolve in his anger and the (very quick) destruction of his uncle Untamo and his people in finale reminiscent of film scores describing a cavalry charge.

The orchestra plays lucidly throughout and is, under Dima Slobodeniouk, sensitive to the changes in tempi and colouration of all the pieces. In the Sibelius piece the orchestra never sounds dissonant or harsh (as in some other recordings), but maintains an atmosphere of subdued threat and gloom. The other pieces all sound lush with a wide palette of orchestral tone, though if I were to criticize something I would say at times it all sounds perhaps a little too smooth.

As mentioned at the beginning, the Klami and Sibelius pieces are slightly older recordings (September 2017 and January 2018 respectively), while the other two pieces were recorded in January 2020.

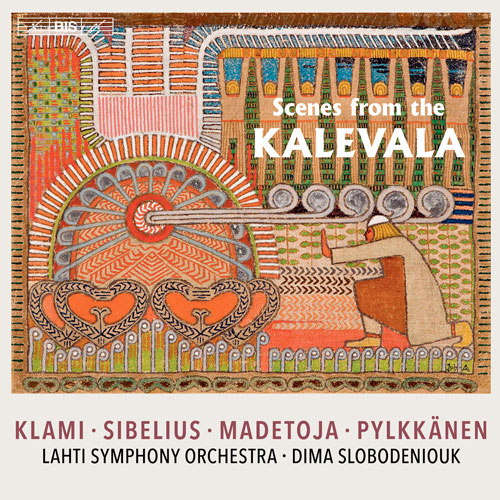

The cover and the inside bear illustrations from the Kalevala by Joseph Alanen (1885–1920), whose highly idiosyncratic paintings look like primitive tapestries. Originally a technical electrician, he re-trained as an artist and had plans to illustrate the whole of the Kalevala, but died before he could complete his work[6]. It is refreshing to see these pictures grace the cover of a Kalevala-related SACD and not the ubiquitous Akseli Gallen-Kalela ones, brilliant as they are. Not only musically does this SACD bring us new views of the Kalevala… My only slight quibble is that only the front cover picture has any relationship to the music on the CD, the other two illustrations featuring scenes not described musically.

The SACD is not in a plastic case, but in a robust, fold-out cardboard sleeve, which is somewhat reminiscent of the good old-fashioned LPs: a more environmentally friendly option, if the design itself needs a little working on, as the end-glue tends to unstick itself (not a major issue, though).

All in all, this SACD is a must for Sibelius enthusiasts seeking to complete their collection for the world première recording of the 1897 version of ‘Lemminkäinen in Tuonela’ alone. But I think its interest lies deeper in the musical depictions of scenes from the Kalevala, which will make it a fascinating album for lovers of (Nordic) mythology as well as Finnish music.

Kornel Kossuth

Dr Kornel Kossuth is an English teacher, writer and poet, who also typewrites poems on the spot as ‘The Poetry Busker’ . He can’t remember when he first fell in love with Sibelius, but it must have been in a Viennese concert hall, where the music was alien, and utterly captivating. He has since been to Finland (of course) but feels he is not nearly enough of a Sibelius junkie – yet.

Bibliography

– Sleeve notes by Kimmo Korhonen of the SACD being reviewed, 2021

– Lemminkäinen. Four Symphonic Poems [Op. 22], edited by Tuija Wicklund, Breitkopf & Härtel, 2013

Footnotes

[1] Interestingly, there are at least two paintings by Akseli Gallen-Kallela, whose paintings illustrating scenes from the Kalevala are among the most famous and influential, of Kullervo in which he is depicted blowing a horn: Kullervo Herding his Wild Flocks (1917) and Kullervo Sets Off For War (1901); there is also the Shepherd Boy From Paanajärvi (1917), which is reminiscent of Kullervo in a number of ways.

[2] Runos 31–36.

[3] My rendition of the Finnish original.

[4] Lemminkäinen goes to Tuonela to shoot the swan in order to win the daughter of North Farm as a bride.

[5] ‘Then follows an especially touching episode in A minor with a charming song (where Lemminkäinen’s mother cradles the well-known [hero] to the life he once had), which the oboe introduces, followed by bassoons, clarinet, violins and so forth, all accompanied by a harp’, H.M. in Hufvudstadsbladet of 14 April 1896. It is the cor anglais that begins the lullaby sequence.

[6] The Tampere Art Museum exhibited a number of Alanen’s paintings on Kalevala themes in an exhibition running 1st February – 24th May 2020; unfortunately the exhibition catalogue is sold out and now out of print.