Jean Sibelius Complete Works (JSW)

edited by the National Library of Finland and the Sibelius Society of Finland

Series III (Works for String Orchestra) Vol. 1:

Opp. 4, 5/5, 5/6, 14, 42, 98a, 98b, 100, JS 34b

edited by Pekka Helasvuo and Tuija Wicklund

SON 629 | €154.08

188 pages | 25 x 32 cm | ISMN: 979-0-004-80343-1

https://www.breitkopf.com/work/6198/16837

The latest release in Breitkopf & Härtel’s JSW Critical Edition, edited by Pekka Helasvuo and Tuija Wicklund, offers a whole genre within Sibelius’s output: his music for string orchestra. This runs to a total of eight works, although several are presented here in more than one version. Three items – the two early versions of the Impromptu and the Paris version of Rakastava – are here published for the first time. It does not include the incidental music to Mikael Lybeck’s Ödlan (The Lizard), which is sometimes played by string orchestra although Sibelius actually wrote it for not for orchestra but for chamber ensemble.

Whilst the composer remains best known internationally for his symphonies, Violin Concerto and tone poems, his music for string orchestra includes several masterpieces and a number of rarely heard gems. The undoubted highlight of the volume is the suite Rakastava, reworked around the time of the Fourth Symphony from the choral piece composed in the 1890s. Rakastava with its ‘ethereal polyphony’ (Tawaststjerna) is relatively well-known (it has been recorded many times since it publication more than a century ago), and differences from the previous printed edition are minor, as the autograph score no longer exists and thus the first edition and parts are the primary sources. What is new, however, is the preliminary orchestral version of the piece, made in Paris in November 1911, which has never been published before and for which the autograph score does still exist (indeed, it is the only source). Sibelius sent this version to Breitkopf but then changed his mind and asked for it to be returned for revision, marking the score ‘Die Bearbeitung ist nicht gut’ (‘The arrangement is not good’). And indeed there were many changes: motifs were adjusted, the solo violin and cello contributions (especially in the first movement) were revised and the keys of the movements were changed.

The earliest of the pieces here is the Scherzo (or Presto) for strings, an arrangement probably made in 1893/94 of the third movement of the B flat major String Quartet, Op. 4 (1890); a double bass part was added but the other four parts remained unchanged. The Impromptu for strings is another arrangement, this time based on material from the melodrama Svartsjukans nätter (Nights of Jealousy), JS 125 (1893) that was later that year incorporated in the fifth and sixth of the Impromptus for piano, Op. 5. In this edition no fewer than three versions are included: in addition to the final version (which has always been popular even though it was not published during Sibelius’s lifetime) there are two preliminary versions: first of Impromptu No. 5 alone, with a distinctive ostinato rhythm in the violas, then a version combining Nos 5 and 6 which in turn was revised: the changes at this stage were mostly alterations to the configuration of repetitions. Both of the early versions are here published for the first time.

The Romance in C major for strings dates from March 1904 and was an ideal work for Sibelius to perform at his concerts with the very small provincial Finnish orchestras of the period. In 1943, following a radio performance by an unidentified conductor, Sibelius told the German conductor Helmuth Thierfelder that the Romance should be played much more slowly slower and with more passion – which suggests that the 1957 recording by Anthony Collins, which clocks in at just over six minutes, with the RPO may be closer to the composer’s intentions than many modern versions that play for five minutes or less.

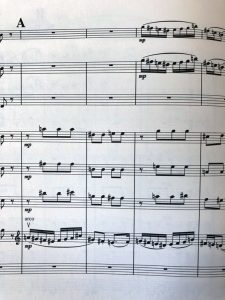

After Rakastava there was a gap of some years before Sibelius turned to the string orchestra genre again; he composed three little suites – Mignonne, Champêtre and Caractéristique – that look innocuous on paper but are fiendishly difficult to bring off in performance because the writing demands the utmost precision and accuracy. For example the cello writing in the Polka from Suite mignonne (at letter A) is so exposed that on one modern recording a solo cello is used instead of the full section – with predictably unconvincing results. Sibelius gave his son-in-law Jussi Jalas some useful performance comments about this suite: that there should be a brief pause before the last eight bars of the first movement, that the Polka should be played slowly and without excessive stretto at the end, and that the start of the Epilogue should be rhythmically straight, without ritardando. In the Suite mignonne piece two flutes are added to the strings. Its companion piece in Op. 98, Suite champêtre, is for strings alone, although an oblique reference in a letter from the publisher Wilhelm Hansen some years later (1930) raises the possibility that he may have considered a version for full orchestra. The third of the suites, the jazzily Tchaikovskian Suite caractéristique, requires a harp in addition to the usual complement of strings.

It is well-known that Andante festivo started life as a string quartet piece in 1922 and that Sibelius’s string orchestra arrangement was made in 1938 so that the composer could conduct its première in a live radio broadcast on New Year’s Day 1939. The new JSW volume reveals the history of the orchestral version in far more detail, pointing out that performances by string orchestras took place in the early 1930s, most likely in an arrangement made by Jussi Jalas under the composer’s supervision.

The introductory text by Tuija Wicklund is especially thorough in the case of Andante festivo, which is fully justified as a radio tape of the 1939 performance (and rehearsal) is the only surviving recording of Sibelius as a conductor. For all of the pieces here, though, there is extensive and reliable documentation concerning genesis, performances and publication history. Seventeen facsimiles of manuscript pages, extensive critical commentaries and source evaluations add further valuable perspective.

Review by Ian Maxwell & Andrew Barnett

Review copy kindly supplied by Breitkopf & Härtel